Cevheri Güven

Tens of thousands of people are imprisoned in Turkey on the basis of accounts given to authorities by anonymous witnesses, which often occurs in politically motivated trials. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), however, has delivered a ruling that could establish a precedent for arrests based anonymous testimony.

The European rights court on Oct. 13 rendered its judgment on the application of Hasan Bakır, a district executive for the Democratic Society Party (DTP), which was shut down in 2009, finding his three-year prison sentence based on anonymous witness denunciations to be in violation of his rights and underlining that the testimonies could not be construed as substantial evidence for conviction.

Criminal procedures in Turkey, however, point in the opposite direction.

One anonymous witness for 4,000 people

In Turkey anonymous witnesses who play roles in politically charged trials are given codenames. One witness codenamed “Garson” (Waiter in Turkish) is possibly the most popular one as he is a witness in a case involving some 4,000 police officers.

The police officers were allegedly named on two SD cards that Garson submitted to the authorities as a list of officers tied to the faith-based Gülen movement. They were removed from their jobs, and nearly 2,600 of them are still under arrest.

The Turkish government accuses the Gülen movement of masterminding a failed coup in July 2016, although the movement denies any involvement. After the abortive putsch, Turkey summarily dismissed tens of thousands of people from the civil service due to their supposed links to the group.

Anonymous witnesses participate in hearings via videoconference from separate locations, with their appearance and voice altered. Garson connects to several hearings every day to give statements. Lawyers who have collected Garson’s testimonies claim to have discovered his identity.

A lawyer from the İstanbul Bar Association who has learned Garson’s identity spoke to Turkish Minute about the discovery on condition of anonymity:

“Everyone knows that Garson is a certain T.Ç., who disappeared on March 31, 2017. His family had filed criminal complaints about his disappearance. We know from the account of Önder Asan, who was also abducted a day before T.Ç., that the two were taken to a secret detention facility where they were tortured for months. As a result, T.Ç. agreed to admit to everything he was told to and was placed in a witness protection program. Asan, who refused to yield, is still under arrest.”

The lawyer said they represent a police officer and a deputy police commissioner who were included on the SD card obtained from Garson. They explain, however, that Garson knows neither of their clients.

“He participated in the hearing via videoconference. It was really hard to understand his speech as his voice was lowered and altered. I asked questions about my clients, and he admitted that he did not know them. He said he knew some Gülenists who were in touch with my clients. But when we asked their names, he could not answer,” the lawyer said.

“Despite all the contradictions and the fact that a single person cannot possibly know 4,000 police officers, over 2,000 people like my clients are behind bars. Garson is just an example of how the Turkish judiciary totally depends on anonymous witnesses in politically motivated trials.”

Selahattin Demirtaş is also a victim

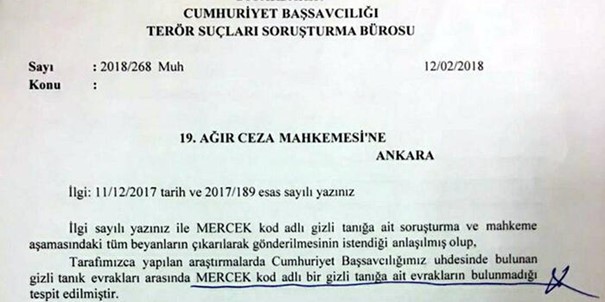

Selahattin Demirtaş, the jailed former leader of the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), is one of the victims of anonymous witnesses. Demirtaş is currently facing up to 142 years in prison in an Ankara court, and his trial involves an anonymous witness codenamed “Mercek” (Lens in Turkish). When the trial began, it was revealed that Mercek never existed. When the court requested Mercek’s testimony, it was informed that “they were not found.”

US pastor Brunson held in prison for two years upon anonymous testimonies

Andrew Brunson, a US pastor who had lived in Turkey for over 20 years, found himself accused of being a spy and a terrorist linked to the Gülenist network based on denunciations by six anonymous witnesses. Brunson spent two years in pre-trial detention until Turkey released him after trial and conviction upon pressure from US President Donald Trump.

The statements provided by six witnesses, codenamed “Dua” (Prayer), “Göktaşı” (Meteor), “Ateş” (Fire), “Serhat” (Border), “Kılıç” (Sword) and “Kama” (Dagger), were widely reported by media outlets close to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Journalist Adem Yavuz Arslan explained the anonymous witnesses in the Brunson file.

“According to the anonymous witnesses who gave statements in the case, Brunson would have become head of the CIA had the July 2016 coup attempt succeeded. Based on these accounts, pro-Erdoğan journalist Nedim Şener alleged that Brunson would convince Kurds to convert to Christianity and establish a separate state. The witnesses actually suggested that a Christian pastor was a follower of Muslim cleric Fethullah Gülen,” Arslan said.

“While these statements had nothing worthy of taking seriously, courts saw them as adequate grounds for arrest. The course of the trial as well as the accounts given by the witnesses were shaped by the bargaining between Turkey and the US. After Turkey’s economy fell into crisis due to Trump’s economic pressure, the witnesses recanted their statements at the request of Erdoğan’s government and started to say the exact opposite of their previous accounts. Brunson was set free after he was tried and convicted. He flew to the US and was welcomed at the White House by President Trump.”

Anonymous witnesses used to suppress dissent

Lawyer Ali Yıldız said the recourse to anonymous statements has become a tool to crack down on the government’s critics:

“While the use of anonymous witnesses has always been abusive since its introduction into the criminal justice system, the targeting of political opponents based on it reached unprecedented levels after 2016. Almost every single politically motivated trial has an anonymous witness. It even became a paid profession for some,” Yıldız said.

“In some instances the witnesses turned out to be nonexistent. They are never actually brought before courts. Selahattin Demirtaş’s case is one of them. The witness statement is referred to in the indictment, but the witness is nowhere to be found, and their identity is unknown.”

Yıldız thinks the latest ECtHR judgment is significant.

“What is of critical importance about the latest ECtHR ruling is that the court has found the inability of defense attorneys to question the anonymous witness and the key role the testimony played in the sentence that was handed down to be in breach of the [European] Convention [on Human Rights]. The recourse to anonymous witnesses worsens the impact on individual liberties of Turkey’s anti-terror laws, which are already ambiguous and arbitrary. Anonymous witness statements serve to fill case files devoid of evidence, which results in people receiving overly harsh sentences on the basis of these statements alone.”