Alin Ozinian

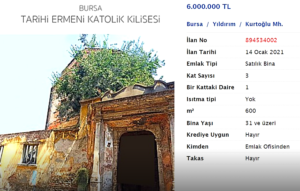

The Armenian Catholic Church of St. Gregory in Turkey’s northwestern province of Bursa, the first capital of the Ottoman Empire, was put up for sale on the local real estate market last week. An unnamed party has advertised the sale of the 190-year-old Armenian church with an asking price of $800,000. The exact location, name of the church and original photos are missing in the online ad due to what the advertiser claimed was “the protection of trade secrets and personal reasons.”

The church was used as a tobacco warehouse and then as a weaving factory after 1923, the year the Turkish Republic was established, and is currently abandoned.

“Historic church that could become a culture and art center/museum/hotel in Bursa. Built by the Armenian population living in this region, the church was sold and became private property following the ‘mübadele — population exchange.’ The church can be used as well for tourism purposes due to its historical location,” reads the advertisement on the Turkish real estate ad site Sahibinden.com.

Aris Nalcı, an Istanbul-Armenian journalist based in Brussels, thinks these kinds of ads shouldn’t be shocking to Turkish society because there’s nothing new about them “In 1915, the lives and the right to property of Armenians were destroyed. The churches put up for sale today are a declaration of the fact of that process. Armenian mansions, Greek houses, Syriac and Armenian churches… You can find all these kinds of ads on Turkish real estate websites. The websites know they’re destroying their credibility by running the ads, but they continue to do it anyway,” he said.

The first attempt to sell the same Armenian Catholic church in Bursa was made in 2016, the Agos weekly Armenian newspaper reported. At the time the price was equivalent to $1.5 million, and although “one or two buyers” showed an interest in the property, it wasn’t sold. The owners of the church building are descendants of the famous tobacco seller Salih Kiracıbaşı, the first president of the Bursaspor football club.

“When the issue was raised in 2016, the real estate agent who was trying to sell the church removed the advertisement. I went to Bursa, drafted a report and wrote an article about ‘selling an Armenian church.’ At the time the topic was widely discussed in the Turkish press and on social media. After seeing my piece the seller sent me a threatening e-mail and said, ‘Don’t ever set foot in Bursa again!’ Now, it’s 2021, and the same church is again for sale. However, this time they have posted miscellaneous photos but none of the church,” Nalcı told Turkish Minute in a phone interview.

Turkish Minute spoke with historian Elçin Arabacı, who focused on cases of dispossession in Bursa between 1840 and 1912 for her doctoral thesis. According to Arabacı, churches for sale are occasionally on the agenda of Bursa’s real estate market because there were many churches in the towns and villages of Bursa province and as well as in the city center.

“According to an official Ottoman yearbook, the 1889-90 Hüdavendigar Salnamesi, there were seven churches: three Armenian, three Greek Orthodox and one French Catholic, and three synagogues in Bursa city center. As far as I know, the Armenian Catholic church in Bursa that is said to have been put up for sale in the past few days is the only remaining church that belongs to Armenians in Bursa and its districts. An Armenian Gregorian church was demolished in 1980, and the Setbaşı primary school and the provincial public library were built on the land,” she said.

Arabacı says there were 69 churches, four monasteries and five synagogues in the 19th century within the borders of today’s Bursa. “Unfortunately, today, you can count the remains of these structures on the fingers of one hand,” she added.

The historian underlined an important point: the link between confiscated Armenian real estate and the Armenian genocide. “Contrary to what was stated in the announcement of the sale of the Armenian church, there is no Armenian community that left Bursa through the ‘mübadele — population exchange.’ The Armenians of Bursa were ‘dispatched’ to the Zor Sanjak [administrative district in the Ottoman Empire] in a declaration dated August 14, 1915 sent by the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ General Directorate of Security to Bursa and its districts. According to official figures, approximately 34,000 Armenians were dispatched from Bursa at the time, and almost all of them were Gregorian Armenians because war allies Germany and Austria prevented the deportation of Catholic and Protestant Armenians. The Armenian villages and neighborhoods of the Bursa Sanjak were largely evacuated.

“The ‘secret’ of how not only churches but also dozens of Armenian factories and hundreds of shops, houses, schools, hotels and taverns changed hands is largely hidden in the work done by the ‘Abandoned Properties Commission’ and local civilian authorities in Bursa during the war years and afterward,” said Arabacı.

The Abandoned Properties Laws (Emval-i Metruke Kanunları), concerning the disposition of property left behind by Ottoman Armenians who were deported in 1915, were promulgated in the Ottoman and Republican periods. According to historian Ümit Selim Kurt: “The most important provision concerning Armenian properties was that their equivalent value was to be paid to the deportees. This never happened. Instead, laws and decrees began to deal with only one topic: the confiscation of the properties left behind by the Armenians.”

Last week, the topic – the sale of a church – was again discussed on Turkish social media, and many people asked if a house of worship could be sold. Some social media users reacted with disappointment. According to their tweets, historic buildings, especially sanctuaries, cannot be sold by private individuals, and the state is required to intervene.

“An Armenian church for sale in Bursa. But is it even possible to put a house of worship up for sale? How can the state and the society allow all this? Shame on you!” Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) deputy Garo Paylan tweeted but was unable to attract any political attention. Neither the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) nor the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) has issued any statements on the issue.

The Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations, also known as the Lausanne Convention, was an agreement between the Greek and Turkish governments signed on Jan. 30, 1923, in the aftermath of the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922. The agreement provided for the simultaneous expulsion of Orthodox Christians from Turkey to Greece and of Muslims from Greece, particularly from the north of the country, to Turkey. The population transfers involved approximately 2 million people — around 1.5 million Anatolian Greeks and 500,000 Muslims in Greece. However, the confiscation of Armenian property was not an outcome of the population exchange of 1923 — as the advertiser asserts — but of the Armenian genocide in 1915.

“There is a well-known answer to the question of how churches can belong to private persons. After the population exchange, Greek Orthodox churches were either converted into mosques as required by the conditions of the exchange, or were sometimes transferred to well-to-do immigrants in return for real estate they abandoned in their countries of origin.

“What is more complicated here is why and how Armenian churches changed hands and were transferred to private parties. However, it is not possible to access the land registry and cadastral records issued after the period of land reform in the Ottoman Land Code of 1858. Although the archives are said to be open, researchers are not allowed to access records in the Ottoman Archive or in the Land Registry and Cadastre Archive.

“However, when a personal inheritance lawsuit is filed, you can see the title deed records with special permission. I learned about this situation from Land Registry and Cadastre Archive officials in 2014. Therefore, it does not seem possible for now to access the records detailing how churches and other Armenian properties were transferred,” said Arabacı.

Following the advertisement of the new sale and the ensuing public discussion, the Armenian Patriarchate of Turkey also issued a statement saying: “It is much sadder for us that church buildings are perceived as a commercial commodity and seen as a source of income by some people. We know that protecting the church buildings, which constitute the cultural richness of our country and which are deprived of their congregation, is a duty of the relevant institutions of the state.”

Nalcı thinks the new owners of old houses of worship in Turkey probably aim to sell the buildings to the old owners. “Sometimes I wonder who will buy these buildings. Maybe they want Armenians or Greeks to reacquire their churches and houses with these kinds of advertisements. You can find different ads when you search for ‘abandoned’ Armenian or Greek properties. Let me give some examples and their prices. They are trying to sell an Armenian mansion in Mardin for $445,000, a Greek mansion in Nevşehir for $82,000 and an Armenian mill in Adapazarı for $205,000. There are too many to list here…”

This is not the first time an old church has been put on the Turkish real estate market. The last example, before Bursa’s Armenian church, was the 1,700-year-old Mor Yuhanna Assyrian church in the eastern province of Mardin, which was put up for sale for nearly $1 million in October 2020. The Mor Yuhanna church, located in Artuklu, is registered as a cultural asset by the Culture and Tourism Ministry but is owned by an individual whose father bought and used the building as a warehouse and a carpenter’s shop.

Selling abandoned churches in various parts of Turkey is not the only controversial practice demonstrating a lack of respect for Christian minorities. Last month a “kebab chef” was criticized for hosting a barbecue in an abandoned church in Şanlıurfa, southeastern Turkey. The 19th-century Armenian church was ruined after treasure hunters ransacked it.

Academic Ohannes Kilıçdağı states: “It is a well-known fact that after the deportation, evacuation and massacre of the Christians in Turkey, churches were used as barns, ammunition depots, prisons, X-rated movie theaters and karate clubs, and of course some of them were converted to mosques. Some churches were dynamited by state officials, and some were gradually destroyed by treasure hunters. The Turkish state did not make any move to preserve and guard these churches and left them to their fate.”