“Jailing peace activists and writers is not new in our country,” wrote the linguist and author Necmiye Alpay this month, in a letter to Pen International, the association of writers, from a women’s closed prison in İstanbul. Ms Alpay — a member of the Turkish-language daily newspaper Ozgur Gundem’s advisory committee — was arrested on August 31, accused of being part of a terrorist organisation and disrupting the unity of the state.

It is one of the many heartbreaking ironies in Turkey that an intellectual, who has fought for peace and coexistence all her life, is today imprisoned on charges of terrorism.

Turkey has a long history of persecuting its thinkers. Those of us who have dedicated our lives to the written word know too well that an article, a poem, a novel, or even a tweet might get us into trouble with the state. But never has it been as difficult and exhausting to be a Turkish journalist, writer or academic as now.

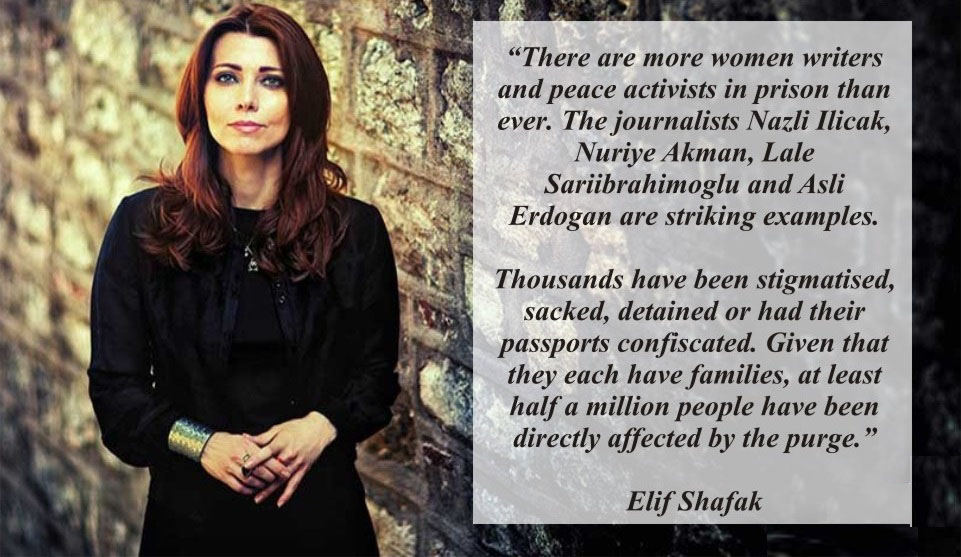

“There are more women writers and peace activists in prison than ever,” Ms Alpay’s letter continued. The journalists Nazli Ilicak, Nuriye Akman, Lale Sariibrahimoglu and the prominent Turkish novelist Asli Erdogan are striking examples. Asli, who is a friend and a colleague, was arrested for having her name on Ozgur Gundem’s advisory committee list. In a message she sent from prison, she says she will suffer permanent injury as she has been denied her medications and mistreated.

There is no doubt that the horrific coup attempt of July 15, which left more than 200 people dead, was a trauma for the Turkish nation. There is no doubt that those who plotted and executed the coup must be investigated or that the accusations of the presence of a Gulenist cabal within the Turkish army are serious.

But Turkey’s liberals and secularists have been strong opponents of military takeovers. This summer, both the liberal media and opposition parties have, in unison, defended a government they were not fond of against the putschists. Instead of cultivating this spirit of unity, the government has launched a widespread purge across society.

Amid the turbulence, thousands have been stigmatised, sacked, detained or had their passports confiscated. Given that they each have families, at least half a million people have been directly affected by the purge. The number of those on the state’s blacklists has escalated to 100,000. Among them are business people, teachers, bank accountants, nurses and doctors.

The witch-hunt against the intelligentsia is particularly keen. Critical voices in the media and academia are accused of betraying the nation and acting as pawns of its internal or external enemies. Once stigma is attached, it is incredibly difficult to wash it off and disprove it: in the space of a day, a writer can be lynched on social media and demonised in pro-government media. If you are a woman, the language of the attacks gets nastier.

Last week saw the beginning of the trial of a teacher named Ayse Celik. Live on a popular TV show in January she talked about the violence in the mainly Kurdish south-east of the country, where the government has clashed with the Kurdistan Workers’ party, saying: “Let the people not die. Let the children not die. Let the mothers not cry.”

Such was the ultranationalist reaction against her that the very next day the presenter of the show had to apologise for allowing her to speak at all. Ms Celik is now charged with “propagandising for the terrorist organisation.”

Intimidation and paranoia permeate Turkish society. We are afraid to write. We are afraid to talk. Never before have we been so scared of words and their repercussions. If the government does not control this purge, it will not only cause injustices that will take decades to heal, but also weaken the credibility of legitimate efforts against putschists.

“The current crackdown on freedom of expression in Turkey is unprecedented,” says Jo Glanville, director of English Pen. “The detention, arrest and prosecution of the country’s leading journalists and writers is deeply alarming. While the government has every justification to investigate the failed coup, the attempt is being used to silence anyone who is perceived to be in opposition to President Erdogan and his supporters.”

The case of the Turkish novelist and journalist Ahmet Altan and his brother, Professor Mehmet Altan, an academic and journalist, is the latest in the escalating tension. The brothers are accused of broadcasting a pro-coup subliminal message on TV to the Turkish people. The accusation is rather Kafkaesque; nobody quite knows what it means. After the two men were detained, more than 300 writers from all over the world signed an open letter urging Turkish authorities to release them and the others, who have been arrested. Our voices fell on deaf ears. Today Professor Altan is arrested and his brother, though at first released, has been taken back into custody.

“The accusations against Ahmet and Mehmet Altan are both absurd and groundless,” says Katie Morris, head of the Europe and Central Asia programme at Article 19, a British human rights organisation that focuses on the defence of freedom of expression. “We call upon the Turkish authorities to immediately release the brothers and to cease the persecution of writers, journalists and intellectuals in Turkey.”

More than 120 journalists have been detained since July 15. Dozens of others have been stigmatised, lost their jobs or been forced to leave the country. The veteran journalist and activist Hasan Cemal dedicated a recent article “to friends in exile”. Turkey’s thinking minds are now scattered all over the world, alone and bruised.

Sürgün — exile — is one of the saddest words in the Turkish language. It is also used to describe a branch or a root that deviates from the trunk of a tree. But we need to understand that it is not Turkey’s writers but the country itself that has deviated from a course — the course of liberal democracy.

Days pass. The government continues to produce new lists of names of people to interrogate or arrest. The motherland that I miss and love dearly, I can no longer recognise.

Elif Shafak is a novelist and journalist

*This article originally appeared in the Financial Times (https://www.ft.com/content/9e7a3e42-6ec4-11e6-a0c9-1365ce54b926)