The Turkish government will at the beginning of 2023 terminate the operations of a commission it set up to examine complaints from individuals who were adversely affected by government decree-laws during a two-year state of emergency (OHAL) in Turkey, local media reported on Monday.

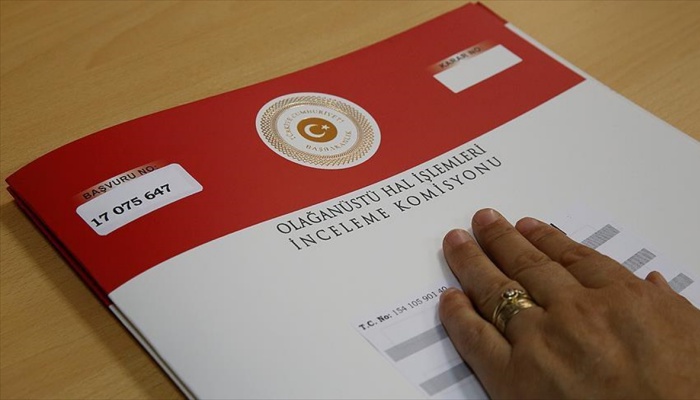

The operations of the commission, which was initially established in the summer of 2017 for a period of two years and whose term was then extended several times by presidential decrees, will be terminated in its sixth year on Jan. 22.

The move to end the commission’s mandate came as part of an omnibus bill submitted to parliament by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), according to Turkish media reports, which added that the petitions of people dismissed by government decrees would be handled by the relevant ministries after the expiry of the commission’s mandate.

According to the bill, the Ministry of Education will handle petitions and fulfill information and document requests for dismissed students and closed private education institutions, while the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK) will do the same for closed television and radio outlets, the Ministry of Labor and Social Security for closed unions and confederations, the Health Ministry for closed private health institutions and the Interior Ministry for closed associations.

The AKP government declared a state of emergency in the aftermath of a failed coup on July 15, 2016 that remained in effect until July 19, 2018.

During the state of emergency, the AKP issued a number of government decrees, known as KHKs, through which 130,000 civil servants were purged from their jobs due to their real or alleged connections to “terrorist organizations.”

The commission accepts complaints regarding dismissal from public service, jobs or organizations; dismissal from the university and the loss of student status; closure of associations, organizations, unions, federations, confederations, private health institutions, private education institutions, private institutions of higher education, private radio and TV stations, newspapers and magazines, news agencies, publishing houses and distribution channels; and the loss of retiree ranking through government decrees.

The commission rejected 106,970 applications out of the 124,235 it had processed since its establishment, according to a written statement it released on May 27. The statement also showed that the commission had received 127,130 applications, ruled in favor of only 17,265 petitioners and was still examining 2,895 applications.

The bill said the commission had examined more than 127,000 applications, without mentioning a specific number, according to local media reports.

Critics have expressed suspicion over the commission’s ability to serve justice.

Purge victims say the commission provides no remedy for them and that they only lose time with their applications pending for years before it. They think the commission was established to prevent them from directly applying to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) as they are first supposed to exhaust all domestic remedies.