Rolling his cigarette between sips of tea, Süleyman Ilcan is excited about a message from jailed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) leader Abdullah Öcalan that could advance peace efforts, but says he has little hope.

“We are in favor of peace, we don’t want war,” the 35-year-old construction worker told Agence France-Presse at a coffeehouse in Diyarbakır, the biggest city in the Kurdish-majority southeast of Turkey.

“All of us are looking forward to hearing the message from Apo but we don’t have much hope,” he said, referring to Öcalan by a nickname used by many Kurds, meaning “uncle.”

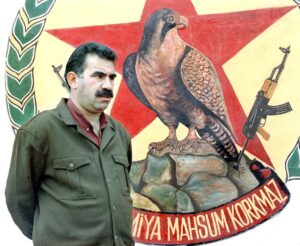

Öcalan, founder of the PKK, which has waged a decades-long insurgency against the Turkish state, is to make “a historic call” to his followers in the coming weeks that many hope will pave the way for a democratic end to the Kurdish struggle for recognition, referred to in Turkey’s public discourse with the shorthand “Kurdish problem.”

With peace efforts frozen for nearly a decade, Turkey’s far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) offered an unexpected olive branch to Öcalan in October, urging him to renounce violence in exchange for a possible early release from a prison on İmralı Island, where he has been serving a life sentence since 1999.

Backed by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the call has renewed hopes of an end to a conflict that has cost tens of thousands of lives.

But many in the southeast are reluctant to trust the process, recalling the tremendous wave of violence that erupted when the last peace initiative was shattered in 2015.

A delegation from Turkey’s pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Equality and Democracy Party (DEM Party) has twice visited Öcalan over the past six weeks, then sat down for talks with Turkey’s main parliamentary factions.

Although no timing has been set for Öcalan’s message, Kurdish politicians are confident it will be soon, and no later than Newroz, the Kurdish New Year, in March.

‘Bittersweet’

Zeki Çelik, who runs a silver workshop, said the idea of Öcalan giving a message “always generates excitement” in Diyarbakır.

“But it’s bittersweet,” the 60-year-old said, adding that many people doubted the sincerity of the government’s peace overtures.

“Elected mayors are removed, there are ongoing police raids and journalists are rounded up,” he said. “There’s been mistrust, so we don’t find it credible.”

Since last year’s local elections, eight DEM Party mayors have been removed and replaced by government-appointed trustees.

Gülşen Özer, the DEM Party’s co-chair in Diyarbakır province, acknowledged the mistrust ran deep, saying it would take time to heal the wounds caused by the state.

“It’s those people who lost their sons that want peace the most, because they don’t want others to have the same pain. They want democracy and freedom,” she told AFP.

‘Bloodshed must stop’

Sedat Yurtdaş of the Tigris Social Research Center said Ankara’s bid to settle the Kurdish problem was likely triggered by the regional upheaval caused by the Gaza war, which set off a domino effect that toppled Syrian strongman Bashar al-Assad and weakened Iran.

“We are on the eve of a historic moment,” he said. “The state sees the Kurdish question needs a lasting solution.”

This time, he said, was different because the initiative came from the state and was made by MHP leader Devlet Bahçeli, who for years was implacably opposed to any rapprochement with the Kurds.

Not everyone saw it that way, with one grey-haired coffee drinker recalling when Bahçeli brought a noose to a rally in 2007, demanding Öcalan be hanged, five years after his death sentence was commuted.

“What has changed since then?” the man wondered, without giving his name.

“I don’t have a grain of hope. We Kurds are always tricked by political parties. If two soldiers happen to be killed near the Iraq border, the process will be dead in the water,” he said.

Despite the fear and the mutual mistrust, both sides need the conflict to end, particularly the Kurds, who were “thirsty for peace” after being traumatized by years of violence, Yurtdaş said.

Restaurant owner Mustafa Kemal Sana, 52, said he wanted peace for everyone because both sides had suffered losses in the violence.

“I want neither police, nor soldiers, nor guerrillas to die. The police are poor sons of Anatolia. They are our sons and brothers. We want this bloodshed to stop.”

© Agence France-Presse