Bünyamin Tekin

An Italian human rights expert has expressed serious concerns over the trial of 41 defendants in Turkey, 14 of whom are minors, accused of terrorism for engaging in routine social and religious activities.

The defendants are charged with alleged membership in a terrorist organization, as part of a decade-long crackdown on the Gülen movement.

The Turkish government, led by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has accused the faith-based Gülen movement of orchestrating a failed coup in 2016, although Fethullah Gülen, who inspired the movement, and the movement deny any involvement. Since the coup, Erdoğan’s government has carried out a sweeping crackdown, investigating more than 700,000 people on terrorism-related allegations, many of them for tenuous links to the Gülen movement.

Held at the İstanbul 24th High Criminal Court, the trial has attracted widespread attention and criticism for its focus on everyday activities such as attending religious gatherings, going to the movies and using food delivery services, which prosecutors have framed as signs of terrorist activity.

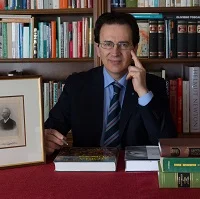

Antonio Stango, chair of the Italian Federation for Human Rights, observed three days of the trial last week, which has drawn international attention for its treatment of normal social interactions as criminal behavior.

Stango, who attended the hearings in İstanbul, described the proceedings as “surreal” and criticized the prosecution for its focus on normal social interactions between the defendants.

“I was there to observe three days of sessions, of hearings of this trial that has come to be known as ‘the girls’ trial’ because among those 41 defendants, there are many girls who are minors, they are less than 18 years old,” Stango said. “And it was quite surreal, because they are accused of such a serious crime, such as belonging to an armed terrorist group. But all that is possible to see from the acts, or the documentation, the questions that have been asked the defendants is that they knew each other. They were usually doing common social activities.”

Stango said some of the defendants shared apartments to be closer to their schools or universities, while others met to read the Quran or pray together. These activities, he said, have been classified by Turkish authorities as terrorist acts. The senior judge overseeing the case questioned the girls about basic aspects of their social lives.

“The senior judge was asking such questions as, ‘Why did you call your friend?’ ‘Why did you meet with your friends?’ And the answers were exactly what I mentioned. It looked like something not based on facts—any fact that can really justify the indicting [of minors] for such a serious crime,” Stango said.

Minors pushed to tears

During his time in the courtroom, Stango noted that the young defendants appeared intimidated by the court proceedings. He recalled seeing at least one defendant moved to tears by the aggressive questioning of the senior judge.

“Imagine a student who is maybe 17 years old or just 18 years old questioned in a tribunal in such a serious trial by a senior judge in a way that I saw at least in one case that pushes the girl to cry. This sort of intimidation doesn’t serve justice, in my opinion,” he said.

Stango expressed concern that the young defendants were not afforded the presumption of innocence, which is a cornerstone of the rule of law. He also observed that the public prosecutor appeared to be aligned with the judges rather than operating independently.

“The judge didn’t look, to my eyes, like a third party in the trial: a person that should be listening to the defendants, to their lawyers, on the one hand, and to the accusations, to the public prosecutor, on the other, and [consider] what he would have heard, take it under examination and make a decision,” Stango said. “The appearance was that the tribunal, the judges that had to make a decision, were aligned with the prosecution. And this is not something that is in line with what a rule-of-law state should give.”

Forced testimony against relatives

Stango also raised concerns about reports that some of the young defendants were pressured to testify against their own relatives during police interrogations. He said he had read case documents suggesting that the minors were forced to make statements implicating their parents, which he deemed a violation of their rights.

“As far as I understood, some of the young defendants, the minors, were also interrogated on the 7th of May, kept up to 16 hours at the police station without the possibility of speaking with a lawyer and without the guidance of a psychologist for minors during the interrogation,” Stango said. “I understand that minors have the right to have a psychologist to assist them during a police interrogation. And apparently, this didn’t really happen, not in every case.”

Trial amid Turkey’s broader crackdown

The trial is part of a broader political crackdown that has been ongoing in Turkey since the coup attempt in 2016. In the years following the coup, the government has carried out widespread arrests and investigations targeting alleged members of the Gülen movement and other political opponents.

“I am familiar with this situation, at least on a general level, and in detail with some specific cases,” Stango said. “Since the 15th of July, 2016, there have been so many — thousands — of cases, that it is very hard for human rights defenders to properly examine them all.”

Stango explained that his organization, the Italian Federation for Human Rights, had presented third-party interventions to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in support of individuals imprisoned under charges of supporting terrorist organizations, often for reasons as trivial as having a bank account linked to the Gülen movement. He also noted that journalists, human rights defenders and even lawyers have been prosecuted under similar charges.

“My impression, and in general, even the impression of the international human rights community, is that too many cases have been conducted in Turkey after July 2016 in a way to put in prison thousands of people just to show that there is a strong will and a strong power to do so,” Stango said.

The ECtHR has time and again found that Turkey violated its citizens’ rights with its misuse of anti-terror laws, particularly Article 314 of the Turkish Penal Code, which criminalizes membership in a terrorist organization. The vague and overly broad application of this law has led to thousands of unjust arrests as well as this trial of minors.

“We have the European Court of Human Rights with specific, very detailed sentences. And I suppose that Turkey, as well as Italy, as well as any other state, should respect the sentences of the European court in Strasbourg,” he said.

In a major protest in Strasbourg earlier this month, over 2,000 demonstrators gathered in front of the Council of Europe headquarters, demanding action against Turkey’s refusal to comply with ECtHR rulings. The protesters, many of whom have been personally affected by the Turkish government’s widespread crackdown, criticized the Council of Europe and the ECtHR for not doing enough to pressure Turkey into abiding by court decisions.