Turks will vote Sunday in local elections as President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan sets his sights on winning back İstanbul, the country’s economic powerhouse, after he was re-elected head of state in a tight contest last year.

The latest elections come in the throes of an economic crisis that saw the rate of inflation surge to 67.1 percent and the Turkish currency crumble against the US dollar.

Why İstanbul matters

Erdoğan was elected mayor of İstanbul in 1994, and his allies held city hall until Ekrem İmamoğlu from the secular Republican People’s Party (CHP) won it in a hotly contested vote in 2019.

Erdoğan can’t easily give up on İstanbul, with its 16-million-strong population, Turkey’s economic powerhouse and a crucial source of patronage for Islamic conservatives.

Berk Esen, an associate professor at Istanbul’s Sabanci University, calls Istanbul “the biggest prize in Turkish politics.”

Erdoğan himself once said, “Whoever wins İstanbul, wins Turkey.”

Erdoğan is fielding his former environment minister Murat Kurum against Imamoglu, whose stated ambition is to become Turkey’s president after Erdoğan’s term ends in 2028 and must secure re-election to remain credible.

Another defeat for Erdoğan?

Opposition CHP candidates are narrowly favored in İstanbul as well as in the capital of Ankara and the Aegean port city of İzmir.

But Anthony Skinner, director of research at Marlow Global, said, “Pre-election polls need to be treated with great caution.”

Soner Çağaptay, director of the Turkish Program at The Washington Institute, wrote that if Erdoğan’s candidates fail to win back Turkey’s key cities, Erdoğan would “emerge from the elections feeling politically vulnerable.”

A win for the opposition would cast Imamoglu as a credible challenger, boosting momentum for the country’s anti-Erdoğan bloc, he said.

That would prompt Erdoğan to double down on his nativist and populist policies at home and abroad, the analyst said.

“There are reasons for the West to keep an eye on how the elections unfold,” said Francesco Siccardi, senior program manager at Carnegie Europe. A large victory for the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) “will consolidate President Erdogan’s power, bringing him closer to [Russian] President Putin’s authoritarian style of government and widening the gap with NATO allies.”

Erdoğan’s last elections?

Erdoğan said early this month that these local elections would be his last, suggesting an end to his more than two decades in power.

He was elected prime minister in 2003, when the premier was the dominant figure in Turkish politics.

A constitutional amendment in 2017 then turned Turkey from a parliamentary system into an executive presidency, abolishing the position of prime minister and ensuring that Erdogan’s grip on power remained unchanged.

Further election successes in 2018 and last year extended Erdogan’s often controversial rule into a third decade.

But analysts question whether it is a farewell or a political maneuver to convince the Turks to grant him a blank check one more time.

Kurdish votes?

Turkey’s pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Equality and Democracy Party (DEM Party) — the third largest in the 600-seat parliament — picked a candidate to run for mayor of İstanbul, whereas in 2019 İmamoğlu won in part thanks to DEM Party’s decision to stay out of race and implicitly support the joint opposition candidate.

Kurds represent an important share of İstanbul’s voters. A survey published on March 20 by Spectrum House showed almost half of DEM Party supporters would back İmamoğlu in this election.

Observers say the DEM Party– accused by authorities of links to outlawed Kurdish militants — will sweep large towns in the Kurdish-majority southeast, including Diyarbakır.

Long ballot, voter apathy

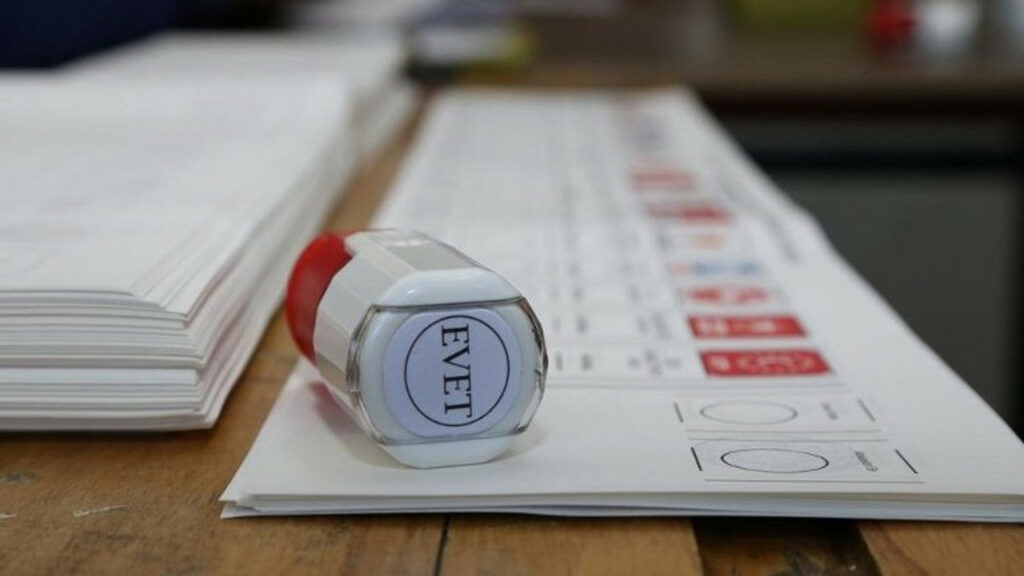

Turkish voters Sunday will elect mayors as well as provincial council members and other local officials. The ballot with İstanbul’s 49 candidates will be 97 centimeters long.

All that choice hasn’t prevented voter apathy, according to the IstanPol Institute.

Turnout in last year’s elections was 88.9 percent, but opposition voters were left disillusioned about their ability to influence politics and change the government.

Similarly, the study showed government supporters are increasingly skeptical about politicians’ ability to sufficiently improve living conditions.

© Agence France-Presse