Ali Dinçer *

Home of the world’s finest conflicts, the Middle East has in the last couple of weeks had no difficulty overshadowing the war in Ukraine and dominating conversations across the world. While the news coming from Gaza has been overwhelmingly bleak from day one, a rare silver lining has been the relative restraint of Turkish president and senior drama queen Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who made unexpectedly cool-headed calls for de-escalation.

In fact, most of his domestic opposition (if we can call them that) has been much more vocal about the crisis. Although an indignant opposition versus prudent government is somewhat normal in the foreign affairs context of a regular democracy, it might seem off-brand for Erdoğan, who has made a career out of taking advantage of every opportunity to lambaste Israel to score popularity points at home.

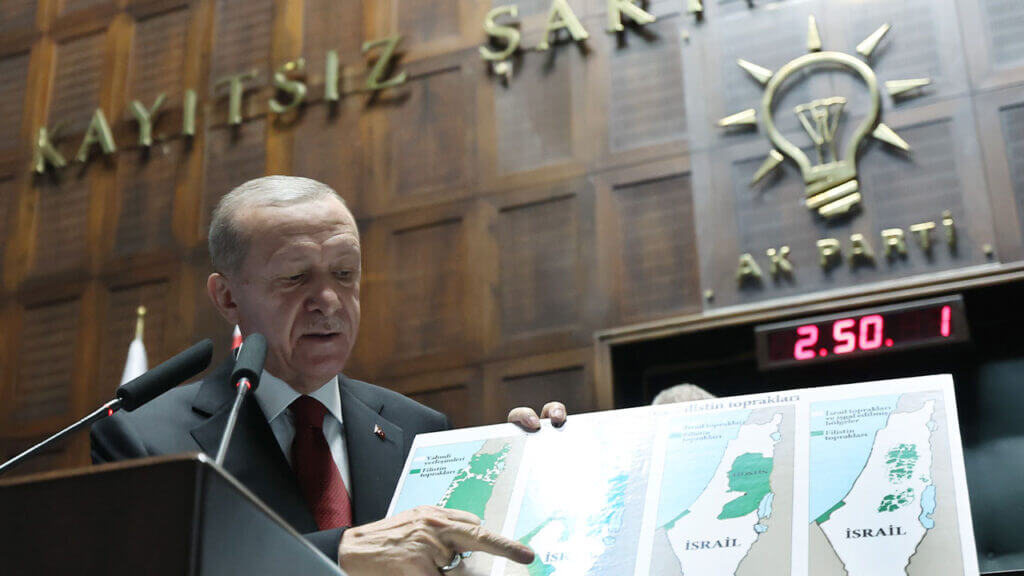

To recap his track record, Erdoğan walked out of a 2009 World Economic Forum meeting after scolding then-Israeli president Shimon Peres on air; he endorsed a pro-Palestinian flotilla that set off in 2010 to supply aid to a blockaded Gaza and ultimately suffered a deadly raid by the Israeli navy; and he responded to the incident by significantly reducing diplomatic ties with Tel Aviv.

Yet in recent years, he had been on a less pompous path to restoring ties with not just Israel but also a number of capitals in the region with which he had previously burned bridges. In 2016 he accepted a $20 million settlement from Israel to smooth over the flotilla incident. When the Islamist NGO who was behind the initiative criticized the deal, he actually disavowed them (true story), turning them into a cautionary tale for anyone who thinks of working with him.

This new reconciliatory foreign policy orientation is part of the reason why the timing of the Gaza escalation has been inauspicious for Erdoğan. In the last decade his brinkmanship showed Turkey’s limitations in the region. He failed to secure the toppling of Syria’s al-Assad. He failed to undermine the international recognition of Al-Sisi, who assumed power in Egypt in 2013 by staging a coup against his Islamist allies. He also failed to draw a significant and sustainable following among Arab populations through his Israel-bashing.

What’s worse, Ankara has in recent years begun to measure the consequences of this brinksmanship through new regional deals that explicitly exclude it or, in some cases, are designed against it. This includes plans for energy cooperation between Greece, Cyprus and Israel as well as an India-Middle East-Europe economic corridor announced by US President Joe Biden on the sidelines of a G20 summit last month as a presumable alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Aside from its business with the EU based on migratory blackmail and its lucrative neutrality in the war in Ukraine, Turkey is generally isolated on the diplomatic level, and Erdoğan is probably aware of this. So far in the Gaza crisis, he has managed to put on the brakes and avoid inflammatory rhetoric. The question is how sturdy his brakes are since they might potentially be further tested in the coming days, depending on the course of this conflict.

To his credit, he has been doing a masterful job navigating the Ukraine theater, selling armed drones to Kyiv on the one hand and providing sanctions relief to Moscow on the other, and brokering grain deals and prisoner swaps, successfully avoiding the wrath of both Putin and Western capitals at the same time.

Yet there are a few factors that make his acrobatics in Ukraine possible, and these are not present in the Israeli-Palestinian theater.

First, Turkish public opinion has little to no interest in the Ukraine war, which gives full maneuverability to the government.

Second, Turkey has been generally accepted and appreciated as a mediator between the belligerents and a backchannel to Moscow, including by certain governments in the Western bloc.

Third, while Erdoğan has been offering Putin backdoors that allow him to circumvent Western sanctions, he has also been acting as a counterweight to Russia’s regional influence on other fronts such as the South Caucasus, Syria and Libya.

Finally, the Ukraine conflict is bogged down in a military stalemate, which tends to cool down the global polarization associated with it. Plus, NATO’s collective defense clause serves as a bulwark against potential regional spillovers. Barring a significant shift in the military balance, the war appears to be bound to turn into one of the classic frozen conflicts of the ex-Soviet world.

In contrast, an overwhelming majority of the Turkish public is emotionally invested in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict due to a number of factors including exposure to years of Erdoğan tirades against Tel Aviv, religious sympathies, left-wing sensibilities, anti-Western sentiment and, for certain parts of the population, antisemitism.

While Erdoğan’s government enjoys full control over traditional media and partial control over social media, a noteworthy protest last week showed Iran might have proxies in Turkey that operate outside government control and exercise a certain degree of influence. Following news of a strike on a Gaza hospital, a seemingly organized crowd of protesters immediately gathered outside a NATO radar station in eastern Turkey and confronted the security forces protecting it. The station is much less known to the general public compared to the US air base in İncirlik and was established specifically to provide protection to NATO members against Iran’s ballistic missiles.

As opposed to the war in Ukraine, no mediator role appears to be available for Erdoğan in Gaza as the position has already been filled by Qatar. To be clear, even in the absence of Qatar, he would not be fit for this role on any level. Despite his political indulgence with Hamas, it’s unclear whether he exercises any actual influence over the militant group. On the Israeli side, he is very unlikely to be welcomed as a peacemaker given his tumultuous track record. With his charm offensive in the West receiving lackluster interest, Erdoğan might be tempted to switch back to escalation mode as a way of undermining the Abraham Accords, a US-led Arab-Israeli normalization initiative that paved the way for energy corridors that exclude Ankara.

Another pitfall is the scenario in which US efforts at containing the crisis fail and the conflict expands to include Lebanon, and by extension, Iran. With the mediator position already off the table, Erdoğan could have a hard time sitting back and watching Tehran become the champion of the Palestinian cause.

Earlier this year Erdoğan secured another election victory and changed his foreign minister in a post-election cabinet reshuffle. Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, a regular ruling party stooge and an uncharismatic yes-man with no discernible foreign policy doctrine of his own, has been replaced by former intelligence chief Hakan Fidan, a shady figure who from the beginning of his public career has been suspected of having ties to Iran. So far, Fidan has been more vocal than Erdoğan on Gaza, and some of his statements have even bordered on hostility towards Washington, D.C., and echoed Tehran’s talking points. While we can assume that Erdoğan will have the last word on foreign policy as long as he’s president, it is worth noting that Fidan is a more powerful figure than his predecessor and is seen as a potential successor to the throne.

There are also reasons why we can expect Erdoğan to remain on the rails.

Even though Turkey is headed for local elections, which are scheduled for early next year, the Turkish autocrat appears to be confident of another victory, and he might not necessarily need Israel as an electoral punching bag. Since their defeat in the presidential and parliamentary elections back in May, the opposition has been in tatters, and their criticism of Israel looks like yet another pathetic attempt at pandering to Erdoğan’s conservative electorate.

Underneath his seemingly out-of-control vitriol, the Turkish president is a pragmatic calculator with a strong sense of self-preservation. His quest for repairing bridges in the region and with the West comes from a realistic assessment of the cost of his previous revisionism and a sober recognition of the facts on the ground.

My guess is that Erdoğan will first want to see where this is going before settling on a clear policy. And as frustrated as he might be with the Biden administration, he is unlikely to test the US resolve in safeguarding Israel against a region-wide hostility, considering the fact that his government has recently downplayed an incident in which US fighter jets shot down a Turkish UAV over Syria.

*Ali Dinçer previously worked for the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.