Ali Dinçer *

A. Rıza Güzel **

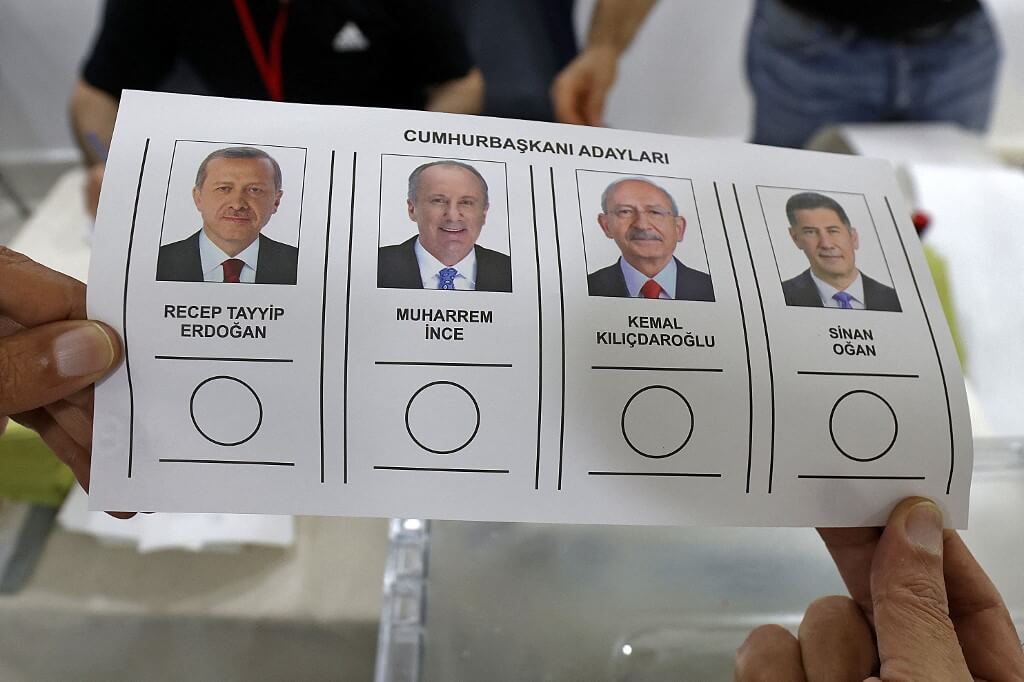

With less than a week before Turkey’s presidential and parliamentary elections, both sides of the race are picking up the pace. As expected, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his ruling circle have shaped their campaign around identity-based symbolism and presented his re-election as a matter of national survival, while the six-party opposition alliance, led by presidential contender Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu and his Republican People’s Party (CHP), have embodied the unifying hope offered by what is perceived by many as a unique opportunity to put an end to Erdoğan’s two-decades-long sway over the country.

Vlad is rooting for Erdoğan. What about the West?

Meanwhile, Erdoğan’s foreign wingmen have been making no secret of their desire to keep him in charge. Russia’s Vladimir Putin, for instance, attended a videoconference two weeks ago for the inauguration of Turkey’s first nuclear power plant, which was constructed by a Russian company, and took advantage of the occasion to extend generous praise for his fellow autocrat’s leadership.

What still remains unclear, however, is whether Turkey’s traditional Western partners are actually rooting for the opposition, which promises to undo Erdoğan’s legacy by re-establishing the rule of law, changing the country back into a parliamentary democracy and aligning it with EU standards.

It is understandable that they would refrain from openly endorsing the opposition nominee as it would do more harm than good by fueling the rhetoric that there is some sort of international conspiracy to override the national will – also known as page one out of any autocrat’s playbook.

Yet there are other signs that suggest a lack of enthusiasm in the West about Kılıçdaroğlu’s presidential bid, most notably the lackluster interest and low-profile welcome he received late last year during his visits to Washington, D.C., London and Berlin.

Grounds for skepticism about Kılıçdaroğlu

In all fairness, Erdoğan’s domestic opponents are not and have never been exemplary champions of liberal democracy. In the early 2000s the CHP famously opposed the EU reforms Erdoğan undertook. While Kılıçdaroğlu has over the years managed to water down the party’s staunchly illiberal stances and sideline some of its ultranationalist factions, he has also been careful not to stand in the way of Erdoğan’s large-scale oppressive crusades against the Kurds and the faith-based Gülen movement, which involved massive human rights violations, widespread crackdowns on the press, military incursions into neighboring countries and the imprisonment of the charismatic Kurdish politician Selahattin Demirtaş. Moreover, the alliance he has built in an attempt to unseat Erdoğan has a number of far-right nationalists on board.

Besides, regardless of whoever is in charge in Ankara, it would be rather unrealistic to expect Turkey to fully return to its pro-Western foreign policy orientation of the last century since the country no longer perceives an existential threat from Moscow nor does it rely solely on NATO for its security.

If elected, Kılıçdaroğlu would probably not be an easy partner for Western capitals to deal with. He and his team’s visibly modest lifestyles and apparent lack of interest in personal financial gain would make them less vulnerable to bribery and blackmail, allowing them to focus on pursuing what they perceive as the national interest. They would tend to drive a hard bargain on many agenda items, particularly on Turkey-EU migrant cooperation which, under Erdoğan, long ago settled into a steady routine.

A strongman and a strong business partner with strong political immunity, Erdoğan, on the other hand, is the ultimate “devil you know.” Contrary to the misplaced conventional wisdom that he is supposedly unpredictable and difficult to work with, he is often nothing but a minor nuisance that can be easily disposed of through lip service and empty gestures. Apart from the ongoing saga of Sweden’s NATO membership, which we believe will be resolved shortly after the elections, it is difficult to point to a diplomatic showdown where he remained confrontational to the bitter end and did not ultimately back down with little or no concessions from the other side.

This is why the Turkish strongman has for years been in this bizarre and toxic arrangement with Western capitals where he can apparently get away with basically anything, including but not limited to, undermining the isolation imposed on Russia over Ukraine, circumventing the sanctions on Iran by defrauding the US banking system, holding Western citizens hostage as bargaining chips, undermining public order in Europe by weaponizing Turkish expat communities and openly threatening dissidents living there, assaulting Syrian Kurds who were instrumental in fighting off the Islamic State, colluding with jihadist factions and engaging in a number of alleged war crimes in northern Syria.

Creative accounting and financial innovation in public debt

Despite all this, and in addition to substantiated allegations of money laundering and terrorism financing, which landed Turkey on the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) gray list for money laundering, Erdoğan’s government still seems to be able to raise billions of dollars in loans and guarantees not only from Saudi Arabia and Qatar but also from Western financial markets. Ankara has been benefiting from favorable treatment in Western jurisdictions where sanctions busters are normally hit with Anti Money Laundering (AML) norm barriers, if not by credit ratings that are prone to be poisoned by extreme political risks, such as those that Turkey carries. Major credit rating agencies including Moody’s, S&P and Fitch still base their reports on the questionable figures provided by Turkey’s official statistics agency, TurkStat, which at this point is as independent of political control as the pope is independent of Catholicism, despite the fact that the agency’s inflation data have repeatedly been refuted by credible private institutions such as the Inflation Research Group (ENAG).

Yet, the most problematic data set from Turkey’s public finances is not its official inflation statistics. Turkey’s government debt-to-GDP ratio, reported as one of the lowest among EMEA and OECD countries, has long been praised by those credit agencies. However, the indirect contractual liabilities of mega construction projects that are undertaken by the Turkish Treasury were never reflected in the credit rating rationale as they should be. This hidden time bomb placed into the books of Turkey’s Treasury is ticking. Along with the liabilities arising from costly international arbitration cases due to the consistent and stubborn violation of international financial laws by Turkish authorities, government debt would double in the coming years, if not the coming months. Taking the direct and indirect public guarantees, most of which are agreed in foreign currency, into the accounts of Turkey’s Treasury, the official debt-to-GDP ratio is well above international norms for the current credit rating.

Capitalizing on the inexhaustible silk road of geopolitics

No one can deny Turkey’s central position for Euro-Atlantic security, particularly in terms of managing the migrant crisis and counterbalancing Russia in certain regional conflicts. Nevertheless, we think it is legitimate to ask whether Western governments are really being wise in their a priori acceptance of the need to keep working with Erdoğan for the foreseeable future.

In our view, their choices are perfectly rational only if we assume that Erdoğan is going to live forever. On the off-chance that he is mortal like the rest of us, however, we would argue that the Western complacency with him is as nearsighted as it is pragmatic.

A sultan with no heirs

When it comes to the sustainability of highly centralized autocracies like today’s Turkey, the issue of succession is essential, as we have been reminded by Erdoğan’s recent health issue on live TV, which led to a brief panic among his ruling elite. And the single greatest iceberg looming on the Turkish regime’s horizon is the fact that its leader does not have an obvious viable heir to his throne.

He has two biological sons, Bilal and Burak, neither of whom is even remotely qualified to fill his shoes. Bilal is not the sharpest tool in the box, as evidenced by his famous lack of perspicacity in a 2014 leaked phone conversation where he was unable to grasp his father’s simple instructions to hide stashes of money, which gave birth to one of the latest idioms of the Turkish language: “to tell something like one would tell Bilal” (Bilal’e anlatır gibi anlatmak), meaning to tell something in such simple terms that even a total idiot would understand. As to Burak, he has been referred to as the “ghost son” since no one even knows where he is or what he’s up to.

His daughter Sümeyye might be the most well-adjusted sibling among them, but the ruling party’s conservative base is unlikely to embrace the idea of a woman taking over the leadership.

That leaves us with the sons-in-law, Berat Albayrak and Selçuk Bayraktar. While Berat appears to be a relatively smart and somewhat charismatic figure, his disastrous stint as his father-in-law’s finance minister from 2018 to 2020 probably destroyed his popularity beyond repair, even among the ruling party voter base, despite the fact that he was only there to implement what were really the president’s ill-conceived economic policies.

The drone guy

Selçuk, chairman of private defense contractor Baykar, which produces UAVs and UCAVs for the Turkish military, is arguably the last standing potential successor. Unlike Berat, this US-educated engineer has not come under political scrutiny by assuming an executive position in government or ruling party ranks.

Baykar’s drones have been deployed in Syria and Libya, where the Turkish military is actively involved. In late 2020 they tipped the balance in Azerbaijan’s favor against Armenia in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. They have also been deployed against the Russian invasion in Ukraine, where they appear to have been registering a more ambiguous performance in the face of an adversary with substantial air defense capabilities. Nevertheless, the drones have been enjoying a palpable popularity in Ukraine and have been globally advertised as Ankara’s contribution to the pro-Kiev cause, even though Erdoğan’s government has been religiously staying out of Western sanctions against Moscow.

Up until now, Selçuk’s relatively apolitical position and his image as some sort of homemade Elon Musk whose fancy gadgets have been conquering the world has been giving him a popularity that grew beyond political lines and won over some of the more chauvinistic segments of the opposition who willingly toe the line when it comes to foreign standoffs and cross-border military adventures.

That significantly changed two weeks ago, when he drew the opposition’s ire by getting into a childish argument with Kılıçdaroğlu over the latter’s reasonable election promise to bring more competition to aviation and astronautics in Turkey. While his grandstanding might have contributed to his popularity among ruling party supporters, it also probably brought him down from his ivory tower above politics and relegated him to an ordinary member of the ruling dynasty. Despite his academic credentials and the good PR he gets, we doubt that Selçuk has what it takes to lead the regime forward after his father-in-law is gone.

Trading today’s stability for tomorrow’s calamity

Let’s return to Western democracies and their apparent contentment with Erdoğan. While prioritizing the status quo over other considerations such as values and settling for a transactional relationship do seem like a rational way of handling today’s Turkey at first glance, the myopia that characterizes this strategy becomes obvious when we consider its long-term implications. The autocracy in Ankara is extremely personalized and devoid of any institutional framework capable of outliving the man at the top and ensuring operational continuity. Every new day under this regime amplifies the magnitude of the chaos that will most likely follow it. By appeasing him at every turn, Western capitals have for years been contributing to the tremendous size of the power vacuum he is bound to leave in his wake, which will end up leaving them with exactly what they fear the most: an unstable, unpredictable and ungovernable Turkey.

As argued in an earlier piece, Kılıçdaroğlu is fighting an uphill battle with a slim chance of victory. He is also no white knight who can make everything right, since his maneuverability is considerably limited by the flaws and quirks of the diverse set of political factions he has lined up under his campaign. Yet it is a shame that he has not received more interest and encouragement from the free world since he and his alliance partners could offer a relatively peaceful way out of Turkey’s years-long downward spiral that seems doomed to end in disaster.

*Ali Dinçer previously worked for the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

**A. Rıza Güzel is an economic historian and political economist. He works as a consultant and financial analyst.