Bünyamin Tekin

The government of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has put a bounty on the head of activist and NBA player Enes Kanter Freedom, on a list that includes many journalists and other athletes.

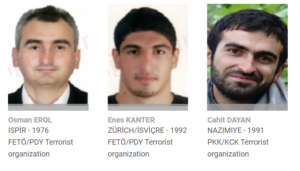

Freedom, who has not had a team to play for since 2022, reportedly for speaking out against human rights abuses around the world, spoke to Turkish Minute about his inclusion on the Turkish Interior Ministry’s “Terrorist Wanted List,” which offers a reward of up to TL 10 million for information that leads to the capture of the wanted person.

Enes Kanter became a US citizen and adopted “Freedom” as his surname in 2021. Since then, he has become a voice for the oppressed in China and around the world.

In interviews and by wearing his “freedom shoes,” Freedom has advocated for the rights of Uyghurs, Tibetans, Hongkongers and others.

In February 2022 he was traded from the Boston Celtics to the Houston Rockets, who promptly dropped him. Many suspect the NBA was punishing him for speaking out against China and trying to silence him.

Freedom has lived mainly in the United States for more than a decade and has used his substantial platform as an international star athlete to condemn Turkey’s pivot towards authoritarianism under President Erdoğan.

Turkey canceled his passport in 2017 and attempted to have him deported from Romania on May 20 of the same year, during one of his international trips. His passport was briefly seized by the Romanian police upon a request from the Turkish government. The NBA said it had worked with the State Department to ensure his release in Romania.

On the Turkish Interior Ministry website, Freedom is described as a member of a terrorist organization.

According to UN special rapporteurs, the vague and imprecise charge of “membership in an armed terrorist organization” appears to be repeatedly misused to target critics of the Turkish government’s policies.

“I’m not the only one. There are so many innocent journalists, academics, athletes, activists and educators on this list. Now their lives are in danger because of the Turkish government,” Freedom told Turkish Minute.

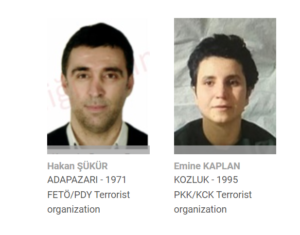

One of the fellow athletes he refers to is famed former Turkish footballer Hakan Şükür, who became a target of Erdoğan after criticizing his authoritarian leanings in 2013. He moved to the US in 2015, and the government confiscated all his homes, businesses and bank accounts in Turkey.

For Turkish sports commentators, Erdoğan’s classification of Şükür and Freedom as enemies of the state meant that even mentioning their names or their past achievements became taboo.

A football announcer for Turkish public broadcaster TRT was taken off the air mid-match while commentating on a 2022 FIFA World Cup match after reminding viewers that it was Şükür who scored the fastest goal in FIFA World Cup history at 11 seconds against South Korea in 2002.

In their absence, the Turkish government has detained the fathers of the athletes in an attempt to persuade them to return to Turkey.

For Freedom, this is the price he must pay for speaking out against human rights abuses.

“I hope the world will open its eyes and put an end to Erdoğan’s human rights violations,” he says.

The human rights abuses Freedom is referring to became widespread after an attempted coup in Turkey in 2016.

Following the coup attempt, the Turkish government launched a massive crackdown on non-loyalist citizens, particularly members of the faith-based Gülen movement, under the pretext of an anti-coup fight.

The Turkish government accuses the Gülen movement of masterminding the failed coup, despite the fact that the movement strongly denies any involvement in the abortive putsch.

Although the Turkish government has classified the movement as a terrorist organization, none of its Western allies have fallen for Ankara’s portrayal and consider the group a civic initiative focused on educational activities. Fethullah Gülen, who inspired the movement, lives in exile in the United States, which has refused to extradite him to Turkey on the grounds that there is no substantial evidence that he committed a crime.

Turkey alleges that Freedom and Şükür are members of the Gülen movement and thus “members of a terrorist organization.”

A country with millions of ‘terrorists’

According to legal experts, Erdoğan is using Turkey’s vague anti-terror legislation as a weapon against his critics.

Officials say Turkish prosecutors have opened more than 2 million terrorism investigations following the 2016 coup attempt.

That number alone says something about the nature of Erdoğan’s crackdown, but the list, which includes Freedom and Şükür, is narrower. It includes 2,309 people who, according to the Turkish government, are “terrorists” at large.

The list consists primarily of well-known figures from the Gülen movement and Kurdish activists, with occasional fighters from the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and some fringe left-wing groups.

One of the people on the list is prominent journalist Can Dündar, who lives in Germany.

Dündar, former editor-in-chief of the Cumhuriyet daily, was arrested and jailed for 92 days for reporting on the interception of Syria-bound trucks allegedly belonging to Turkish intelligence. He was arrested on Nov. 26, 2015 and released on Feb. 26, 2016 following a Constitutional Court decision.

Shortly after his release and an attack on him, Dündar quit his position at Cumhuriyet and left Turkey, as scores of other journalists under pressure have done. He has lived in Germany since June 2016.

Speaking to Turkish Minute about his inclusion on the wanted list, Dündar said he “was not surprised.”

“Because I know how ‘generous’ Erdoğan is in calling his opponents terrorists,” Dündar said.

“Because of this perverse mentality, Turkey has become the country with the largest number of ‘terrorists’ in the world,” Dündar said, adding that he believes this will erode the concept of “terrorism” and further discredit Erdoğan in the eyes of the world.

Both Dündar and Freedom say that the government putting bounties on their heads can incentivize would-be vigilantes to harass or even physically harm them.

“Pointing to us as a target for their followers in the fashion of Wild West-style ‘bounty hunting’ can pave the way for aggressors and lead to devastating consequences,” Dündar said.

Palestinian politician on Erdoğan’s wanted list

People Erdoğan put on his wanted list does not just include Turks who are at odds with him.

Palestinian politician Mohammed Dahlan is included on the list and is accused of being a member of “FETÖ,” a derogatory term used by the government to refer to the Gülen movement as a terrorist organization.

Dahlan, who had been an outspoken critic of President Erdoğan, faces an arrest warrant in Turkey on accusations of playing a role in the 2016 attempted coup, seeking to overthrow the constitutional order and various espionage-related charges.

He has been on the wanted list since 2019 and had a $1.7 million bounty on his head, which was valued at TL 10 million at the time.

Erdoğan wants to silence critical voices abroad

Cevheri Güven, another Turkish journalist who lives in exile in Germany and is on Erdoğan’s wanted list, also spoke to Turkish Minute.

Güven is an investigative journalist whose videos on YouTube in which he talks about the Turkish government’s corruption and shady relations attract millions of viewers.

Journalists who fled Turkey following the coup attempt to avoid jail on bogus terrorism or coup charges such as Güven have established their own news outlets and have become the major source of news for some Turks in a country where 90 percent of the national media is owned by pro-government businessmen who toe the official line.

Güven has recently been facing growing pressure and threats from pro-government circles in Turkey as his videos continue to reach a large audience, even attracting more viewers than some mainstream news outlets in Turkey.

Photo: Barbaros Kaya

“Erdoğan initially bombarded journalists with lawsuits seeking damages. When hundreds of lawsuits filed by a large team of lawyers were not enough to silence journalists, charges of terrorism and espionage began,” Güven said.

“Thus, he succeeded in arresting journalists and silencing many of them. Journalists like me, who managed to leave the country and continue their work, are a difficult problem for Erdoğan to deal with. The videos I make are viewed more than 7 million times every month,” Güven said.

“The address of the house where I live in Germany was revealed, my name was put on the terror list and an extradition request was sent to Germany. All this was done to make me stop being a journalist,” he added.

The so-called Terrorist Wanted List includes at least 13 other Turkish journalists living in exile: Bülent Keneş, Abdullah Bozkurt, Ahmet Dönmez, Tarık Toros, Adem Yavuz Arslan, Said Sefa, Arzu Yıldız, Levent Kenez, Hasan Cücük, Sevgi Akarçeşme, Erhan Başyurt, Bülent Korucu and Abdülhamit Bilici.

Erdoğan attempted to amend Turkey’s anti-terror law in 2005 with a bill that introduced the term “unarmed terrorist organization”

It was never included in the anti-terror law due to a massive backlash. Nevertheless, Erdoğan persisted with the idea of labeling individuals or groups as “terrorists” even if they do not carry weapons or engage in violence.

“It is necessary to redefine terrorism to include those who support such acts,” Erdoğan said in March 2016 after a bombing in the Turkish capital of Ankara that killed 37 people.

“There is no difference between a terrorist holding a gun or a bomb and those who use their position and their pen for their goals [to weaken Turkey]. This can be a journalist, a lawmaker or an activist,” he added.

For exiled journalist Dündar, accusing people of terrorism and targeting them with such lists is itself a crime and should be punished.

“I believe that in order to repel this attack, it could be useful for us ‘terrorists’ to act together within the framework of the law against these real ‘terrorists’ who condemn us without trial,” Dündar said.