A recently published book tells the story of teacher Halime Gülsu, who died in a Turkish prison in 2018 due to deprivation of a medication she was taking for lupus erythematosus, the Stockholm Center for Freedom reported.

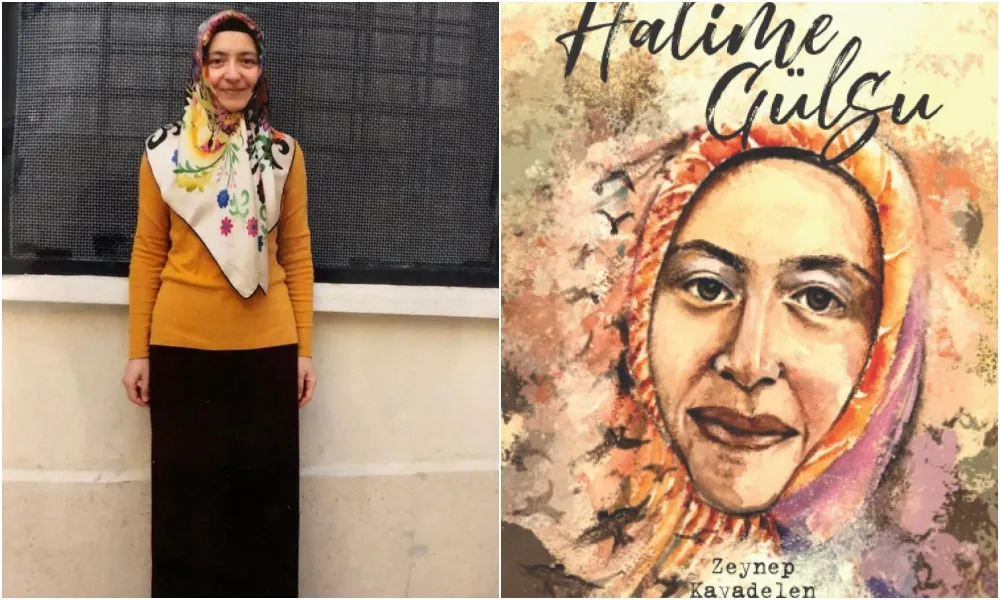

Written by Zeynep Kayadelen and published by the US human rights organization Advocates of Silenced Turkey (AST), the book, titled “Halime Gülsu: The Heavenly Teacher Murdered in Prison,” is based on the accounts of Gülsu’s cellmates who witnessed her final moments as well as friends and family.

Gülsu, who was arrested on February 20, 2018 along with dozens of other women for allegedly helping the families of people jailed for alleged links to the faith-based Gülen movement, died in a prison in Mersin provincein April 2018. She suffered from lupus erythematosus and was reportedly deprived of the medication she was taking for the disease while in jail.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been targeting followers of the Gülen movement, inspired by Turkish Muslim cleric Fethullah Gülen, since the corruption investigations of December 17-25, 2013, which implicated then-prime minister Erdoğan, his family members and his inner circle.

Dismissing the investigations as a Gülenist coup and conspiracy against his government, Erdoğan designated the movement as a terrorist organization and began to target its members. He intensified the crackdown on the movement following an abortive putsch that he accused Gülen of masterminding. Gülen and the movement strongly deny involvement in the coup attempt or any terrorist activity.

Four days before her death, Gülsu wrote a letter to the Prime Ministry Communications Center (BİMER) describing her health problems and explaining that not taking her medication could have critical consequences for her. However, the relevant prison administration and BİMER paid no attention to Gülsu’s request for her medication, which led to her death. After Gülsu’s death, human rights defender and Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) deputy Ömer Faruk Gergerlioğlu revealed Gülsu’s letter to BİMER.

“In her letter, Gülsu said she had not been able to get her medication for two months. I have received her autopsy report. The case is exactly as I suspected in my capacity as a doctor. All her organs were severely congested. What tremendous negligence. I will pursue this death until justice is served,” Gergerlioğlu, who is a medical doctor by profession, said at the time.

A year after Gülsu’s death, prosecutor Zeki Topaloğlu, who led the investigation into Gülsu’s case, announced his decision not to prosecute any official who may have played a role in her death.

Critics have slammed Turkish authorities for refusing to release critically ill prisoners. Gergerlioğlu previously said critically ill political prisoners were not released from prison “until it reaches the point of no return.” He depicted the deaths of seriously ill prisoners in Turkey who are not released in time to receive proper medical treatment as acts of “murder” committed by the state.

According to the most recent statistics published by the Human Rights Association (İHD), the number of sick prisoners is in the thousands, more than 600 of whom are critically ill. Although most of the seriously ill patients have forensic and medical reports deeming them unfit to remain in prison, they are not released. Authorities refuse to free them on the grounds that they pose a potential danger to society.