Kurds in Turkey trust the European Union and the United Nations more than the Turkish judiciary, presidency and parliament when it comes to human rights issues, according to a survey commissioned by the Tahir Elçi Foundation.

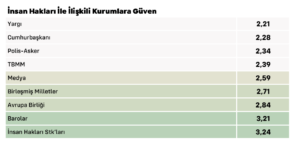

According to the survey that Rawest, a polling firm that focuses on Turkey’s East and Southeast, conducted on 1,363 Kurds in October, respondents give the lowest scores to government institutions in terms of trust in institutions regarding human rights issues.

On a scale where 1 means they are not trusted at all and 5 means they are extremely trusted, none of the legislative, executive or judicial branches of government score 2.5, according to the findings of the survey, which indicates that respondents trust the UN and the EU more than they trust Turkish government institutions on human rights issues.

The institutions that respondents trust the most are bar associations and civil society organizations working in the field of human rights.

According to the survey, two-thirds of respondents, who were all Kurds, think the state violates human rights the most, followed by men, the media and corporations.

Kurds are Turkey’s largest ethnic minority, making up around 18 percent of the population. The group has faced a long history of discrimination and violence in the country. They are often pressured not to speak their native language. Authorities frequently claim that people speaking in Kurdish are actually chanting slogans in support of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which has been leading an armed insurgency against Turkey’s security forces since the ’80s in a campaign that has claimed the lives of some 40,000 people.

Prohibitions against the use of Kurdish in Turkey go back many years. Kurdish language, clothing, folklore and names had been banned since 1937. The words “Kurds,” “Kurdistan” and “Kurdish” were among those officially prohibited. After a military coup in 1980, speaking Kurdish was officially forbidden even in private life.

Seven out of 10 Kurdish youths in Turkey are subject to occasional or frequent discrimination, according to a December 2020 survey by Rawest.

The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), which has increased its crackdown on Kurds, especially after the collapse of Ankara’s reconciliation process with the outlawed PKK in 2015, has been criticized by dissidents for allegedly returning to the methods of the 1990s, which were marked by enforced disappearances and unsolved murders, with many still searching for the perpetrators.

According to the Rawest survey, 73 percent of the respondents believe that the human rights situation has deteriorated in Turkey in the last decade.

Respondents believe that the number of people imprisoned on political charges has increased in Turkey in recent years, according to the survey, which also found that more than half of the respondents believe that violence by state security forces, strip-searches and torture have increased in recent years.

Turkey has been experiencing a backsliding in human rights in the last decade that has further worsened since a failed coup in 2016.

Political and civil rights in Turkey have deteriorated so dramatically under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s rule that according to Freedom House Turkey remains “not free” with a score of 32/100, in the same category as Russia, China and Iran.

According to human rights watchdogs, Turkish courts systematically accept bogus indictments and detain and convict without compelling evidence of criminal activity individuals and groups the Erdoğan government regards as political opponents, among them journalists, opposition politicians, activists and human rights defenders.