Journalists critical of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government have been prevented from covering the swearing-in of a new member of Turkey’s Constitutional Court, Deutsche Welle Turkish edition reported on Monday, adding that one of its own reporters was included in the ban.

According to DW, the names of several journalists were removed from the guest list for the swearing-in ceremony of former Deputy Interior Minister Muhterem İnce, which was scheduled to take place at 2 p.m. local time on Monday, upon instructions from the Turkish presidency’s communications director Fahrettin Altun.

A member of the Court of Accounts and one of the founders of the pro-government Foundation for the Expansion of Knowledge (İlim Yayma Vakfı), İnce was elected as a member of the top court earlier in October in yet another development raising concerns about the politicization of Turkey’s judiciary.

Officials from the Presidential Communications Directorate reportedly requested the list of journalists who will cover the ceremony from the relevant authorities of the Constitutional Court and then crossed off the names of some of them, including DW’s court reporter Alican Uludağ.

The journalists were informed individually about the development by officers from the Constitutional Court.

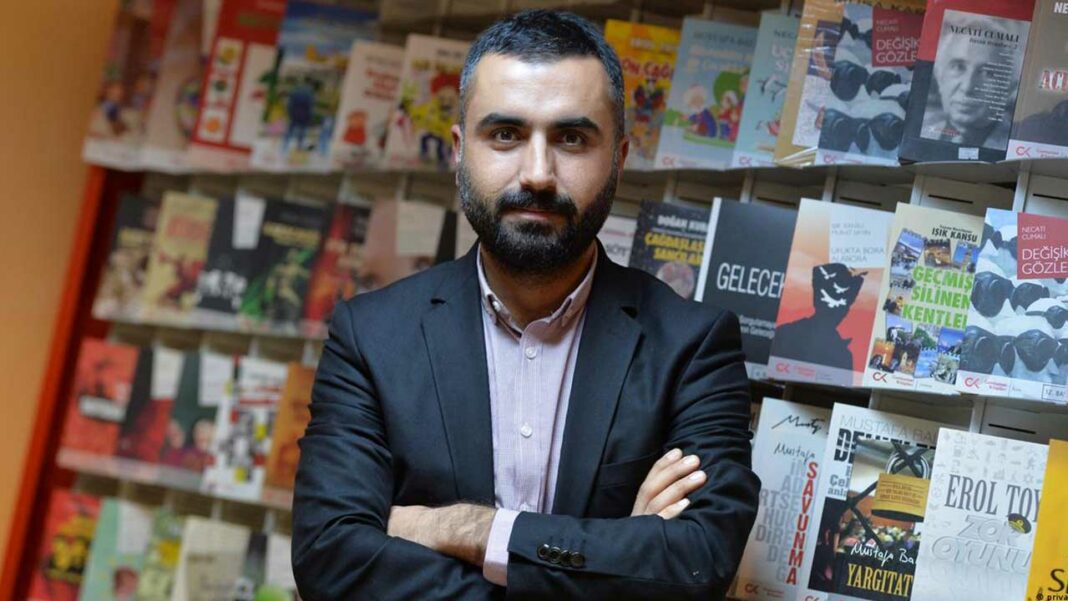

Uludağ on Monday said in a series of tweets that although he was initially invited to the event by the Constitutional Court, the Presidential Communications Directorate “placed an embargo” on his name at the last minute and he was removed from the guest list.

AYM'de bugün saat 14:00’da yeni üye Muhterem İnce’nin yemin töreni yapılacaktı. AYM önce törene davet etti. Ancak son dakika İletişim Başkanlığı tarafından adıma ambargo konuldu. Bu nedenle davetli listesinden çıkarıldım. Sansür yasası yürürlüğe girmeden sansür ve yasak başladı.

— Alican Uludağ (@alicanuludag) October 17, 2022

“Censorship and prohibition began before the censorship law came into effect,” the reporter said, referring to the “disinformation” law approved by the Turkish parliament last week that cements the government’s already-firm grip on social media platforms and news websites while criminalizing the sharing of information.

Critics from within and without Turkey describe it as yet another attack on free speech in the country, with the criticism mainly focusing on Article 29, which amends the Turkish Penal Code by adding a provision (Article 217/A) that would subject persons found guilty of publicly disseminating “false or misleading information” to between one and three years in prison and would increase by half the penalty for offenders who hide their identity or act on behalf of an organization.

“The communications directorate has clearly established tutelage over the constitutional judicial institutions. The fact that the Constitutional Court, which was given the task of protecting fundamental rights and freedoms, doesn’t resist this tutelage, is worrying for press freedom,” Uludağ added.

The journalist further said that the directorate canceled his press card at the end of September because he spoke out against the “disinformation” law and then prevented him from covering the swearing-in ceremony because he asked Altun about the negligence that led to the death of 41 miners in a coal mine explosion in northern Turkey last week.

“They have declared war on critical journalism,” Uludağ said, referring to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his AKP government.

Rights groups routinely accuse Turkey, which has a poor record on freedom of the press, of undermining media freedom by arresting journalists and shutting down critical media outlets, especially since Erdoğan survived a failed coup in July 2016.

Dozens of journalists critical of the government were jailed in Turkey, known as one of the top jailers of journalists around the world, on bogus terrorism or coup charges following the abortive putsch as part of an anti-coup fight launched by the government. Some of these journalists have been released from prison after serving their sentences.