Bünyamin Tekin

He dropped his wife and daughter at the spring festival at school so he could go downtown and run some errands. It was a sunny spring day, and Mehmet Alp, a chemistry teacher in southeastern Turkey, didn’t have a care in the world until a white Volkswagen Polo cut him off.

One of the passengers in the car called out to him. Thinking it might be one of his colleagues from his high school, Alp leaned into the car to see who it was.

“I found myself sitting next to them after someone behind me pushed me into the car,” Alp said.

“‘We are police. Don’t worry,’ one of them told me. They were polite in the beginning. I was relieved after they said they were the police,” Alp said. He was worried about being kidnapped by Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) militants, who abducted state employees from time to time.

He was dead wrong. The car started to drive around the southeastern town of Cizre, on April 18, 2015.

“‘These four, they are your students. They joined the PKK. Gülenists [a faith-based movement targeted by Ankara] encouraged them to do it,’ they told me. I had no idea what they were talking about.”

When a message from Abdullah Öcalan, the jailed leader of the separatist PKK, was read out loud in the Kurdish-majority city of Diyarbakır in 2013, many hoped that the decades-long war between Ankara and the Kurds, which had claimed thousands of lives, would soon be over. A ceasefire had been declared, which was in effect when Alp faced questions from the men who introduced themselves as police.

There were people in 2013 who did not buy into the declared intention of the government about the ceasefire with the PKK.

“You can’t fight on two fronts,” Kamil, a former leftist militant who spent time in jail after a 1980 coup, told me at the time.

“We are at war in Syria. The government had to stop operations against the PKK. No peace is coming any time soon,” Kamil said, referring to the civil war that broke out in Syria in 2011, where Turkey supported the rebels against Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

You can’t fight on two fronts. Looking back, it might as well have been true about the political war Turkey’s then-prime minister and current president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was fighting at the time.

After the proclamation of a ceasefire between the government and the PKK, protests erupted in May 2013 against a construction project in Istanbul’s Taksim Square that turned into countrywide protests against the government of then-prime minister Erdoğan. His Justice and Development Party (AKP) was a coalition of liberals and former Islamists who denounced their old ways. Although he showed momentary anger at protests here and there, Erdoğan and his party seemed very liberal when it came to rights and freedoms in the first decade of his rule.

That is until the protests erupted in Gezi Park. Having agreed on a ceasefire with the Kurdish front, Erdoğan turned his gaze to this urban social group, the secular children of the former ruling class in the country.

Turkey’s leader, having enjoyed popular support with 50 percent of the vote cast for his AKP in 2011, came out guns blazing. He labeled the protesters “bandits” and ordered the riot police to clamp down on their peaceful protests.

The protests were violently suppressed, leading to the death of 11 protestors due to the use of disproportionate force by the police.

The plans to demolish Gezi Park were suspended. Although it seemed calm after a month of clashes between police and protestors, there was another storm brewing.

In December of that year, bribery and corruption investigations shook the country. The probe implicated, among others, the family members of several cabinet ministers as well as Erdoğan’s children.

Despite the scandal resulting in the resignation of the cabinet members, the investigation was dropped after prosecutors, and police chiefs were removed from the case. Erdoğan, officials of the ruling AKP and the pro-government media described the investigation as an attempt to overthrow the government.

Dismissing the investigations as a conspiracy against his government by the Gülen movement, a group inspired by Muslim cleric Fethullah Gülen, Erdoğan designated the faith-based movement as a terrorist organization and began to target its members.

Having dealt with the Gezi protests, Erdoğan allied with the former secular elite, retired and active duty generals, in order to gain the upper hand in his war against the Gülenists. He eventually locked up thousands, including many prosecutors, judges, and police officers involved in the investigation.

However, his efforts to fight one battle at a time meant that he would always have a battle to fight. After gaining ground against Gülenists by the purge he initiated, he angered Kurds, with whom he had a ceasefire, by tacitly supporting an offensive against the Kurds of neighboring Syria.

In 2014, the war in Syria, which by this time had turned into “the war of all against all,” raged on. Syrian Kurds were fighting an existential war against the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), which had taken control of large swathes of land in Iraq and Syria and had the Kurdish border town of Kobani under siege.

Enraged by Erdoğan’s inaction to support the Kurds against ISIL, in October 2014 Turkey’s Kurds took to the streets to protest, which descended into violence that killed more than 40 people.

Erdoğan was not just turning a blind eye to the ISIL onslaught. If he were to keep the new allies he approached to have the upper hand against the Gülenists, namely, the secular military elite who had been jailed or prosecuted over alleged coup plots between 2007 and 2013, he needed to part ways with the Kurds as the nationalist secularists abhorred the ongoing peace talks.

So Turkey’s embattled leader fortified the military bases in the Southeast. The PKK was not ignorant of this, and they entrenched themselves in the cities.

Back to April 18, 2015. Alp, a teacher forced into a car by men identifying themselves as police, was facing questions about his students joining the PKK at the directive of Gülenist prep school teachers.

At its peak, the Gülen movement, a worldwide civic initiative renowned for its educational activities, operated schools in 160 countries, from Afghanistan to the United States. In Turkey, the network had run thousands of educational facilities, including schools, prep schools, universities and dormitories.

Now the questions Alp faced should make sense. Gülenists and Kurds were being bundled into a target Erdoğan would go on to relentlessly attack in the years to come. At the time, pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) leader Selahattin Demirtaş, who has been in jail since 2016, was the fiercest opponent of Erdoğan, along with Gülen movement members. And the country was heading for a general election in June 2015.

The men questioning Alp were forcing him to sign a statement that the pro-Erdoğan media would use to show that Gülenists were allied with the outlawed PKK and recruited militants for them.

“‘You don’t see it, teacher. Don’t dare oppose us. Soon, all hell will break loose,’ they told me,” Alp said, adding, “And indeed it did.”

“I don’t know whether they were referring to the clashes that would take place that summer in southeastern Turkey, or the purge to take place after an attempted coup in 2016,” Alp said. “But indeed, one can say all hell broke loose either way.”

“After we left the city, their attitude changed. They started to shout at me and insulted me. I realized it was not going to end well,” Alp recounted. “One of them pointed a gun at me. ‘We will kill you here,’ they said. ‘Just sign this statement or else.'”

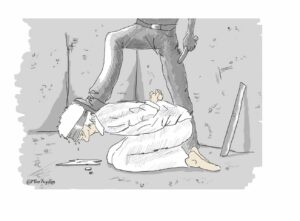

Alp started crying as the man holding the pistol pushed the gun against his forehead.

“I had a nervous breakdown. I started shaking and having convulsions. Realizing that I was having a fit and therefore of no use to them, they threw me out of the car in the middle of nowhere. I stayed there for a while, I don’t know how long. I was unable to move my legs. After that, I hitchhiked home,” Alp said.

In the June 7, 2015 general election Erdoğan’s AKP lost its parliamentary majority, thanks to the historic number of votes cast for the HDP. After this loss, he realized the legitimacy the peace talks provided to the pro-Kurdish cause as a legitimate part of negotiations on the Kurds’ demands of recognition was detrimental to his party’s electoral success. After all, the predecessors of the pro-Kurdish HDP were all banned and labeled as offshoots of the outlawed PKK by the secular establishment.

Erdoğan wanted to go back to business as usual with regard to the Kurds, allying with the same old establishment along the way. So he reignited the war. As both sides prepared for a collapse of the peace talks, this meant the entire Kurdish-majority region would see prolonged clashes between the PKK and the security forces, which would have devastating consequences for the civilian population.

“My wife, also a teacher, worked in a neighborhood controlled by the PKK. I worked in a neighborhood controlled by the police. She did not feel safe going there. I did not feel safe going to my school, either,” Alp said. He added that out of fear he told no one about the episode with the armed men.

“The city of Cizre was a war zone,” Alp said. “It was indeed hell.”

Imprisonment over Gülen links

Alp was imprisoned in May 2016 over his alleged ties to the Gülen movement.

While he was in prison a coup attempt took place in Turkey on July 15, 2016, which dramatically changed the political landscape in the country, as the government launched a crackdown on political opponents under the pretext of an anti-coup fight.

Despite Alp being in prison at the time the coup unfolded, he was charged with coup involvement.

Starting from July 15, 2016, when the coup attempt took place, Alp and other inmates who were jailed over Gülen links were denied medical attention.

“I had trouble with my bowels. I had to see a doctor. When the doctor finally came, he said he was given clear instructions not to treat Gülenists,” Alp said.

Two months later, when they finally took him to a hospital, the doctor there told Alp that he had colon cancer. But his troubles did not end there.

In May 2017 he was manhandled out of prison in Ankara into a civilian car, again by people identifying themselves as police. They drove him hundreds of kilometers to the anti-terrorism department in the southeastern city of Şanlıurfa, where he was before the 2016 coup bid.

Alp said he was exposed to torture for 24 days at the hands of the police, who wanted him to incriminate people he did not know. The torture he underwent included brutal beatings, sleep deprivation and denial of the medicine he had to take for hypertension, along with other medical conditions. The torture led to internal bleeding, and he was again denied medical care.

“They forced me to sign a statement saying that I did not want to take my medicine while I was in police custody,” Alp said.

The 24-day torture ended when he had to appear in court for his trial.

“We won’t only torture you, we will also torture your wife, and your children will end up in foster care. So if you love your family, then don’t tell the court that you were tortured,” Alp quoted his torturers as saying.

“You are going to be released by the court. And we will take you back here to finish our business,” Alp said he was told.

“Indeed, when they took me back to Ankara, the hearing was very short. The police gave the judge a yellow envelope. After the judge opened the envelope, he ordered my release pending trial. They took me back, where they tortured me for another 17 days,” Alp said.

“I had to sign whatever they wanted me to sign. Otherwise I was going to die there,” Alp said.

After he signed the statement they had prepared, he was jailed again. He was released by a court pending trial in 2018, after which he fled to Europe to seek asylum.

On Monday, Alp testified before a panel of judges of the Turkey Tribunal, a civil society-led symbolic international tribunal established to adjudicate recent human rights violations in Turkey.

“I decided to speak out so that maybe others won’t experience what I have been through,” Alp said. “That is what I hope.”

Turkey has been experiencing a deepening human rights crisis in recent years.

After the abortive putsch, ill-treatment and torture became widespread and systematic in Turkish detention centers as evidenced by the UN special rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment in a report based on his mission to Turkey between November 27 and December 2, 2016. Lack of condemnation from higher officials and a readiness to cover up allegations rather than investigate them have resulted in widespread impunity for security forces.

On the last day of the hearings in Geneva, the tribunal will announce its verdict, which will also be published on the website.