Alin Ozinian

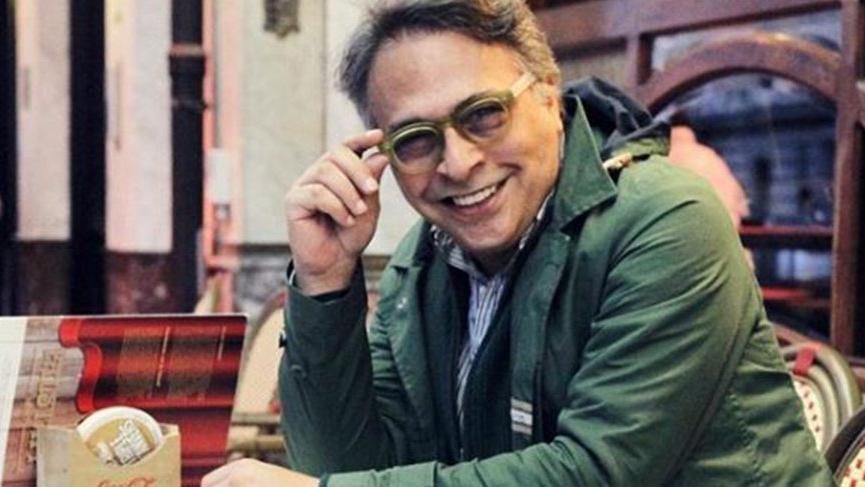

Barbaros Şansal, one of Turkey’s most famous fashion designers and LGBTI+ activists, moved to northern Cyprus because he felt his life and property were not safe in Turkey. Şansal is an outspoken critic of Turkey’s political scene and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), which made his life intolerably difficult in Turkey.

Şansal was attacked and beaten up by a nationalist mob at an Istanbul airport and then jailed in January 2017 due to a controversial video he posted on New Year’s Eve. In the video he criticized Turks for attending New Year’s Eve celebrations despite problems in Turkey including mass detentions, corruption, rape, bribery and bigotry. “I won’t celebrate. Do you know what I’m gonna do? I will drink all the drinks in this bar and then more at home,” Şansal said in the video before adding, ”Drown in your shit, Turkey!”

After being taken into custody by the police at the airport, he appeared in court and was arrested the following day, charged with “inciting the public to hatred or hostility” under Article 216 of the Turkish Penal Code. Şansal said the words he used were “a satire against discrimination” and denied the accusations leveled against him.

Şansal was released from Silivri Prison, where most of Turkey’s political prisoners are jailed, on March 2, 2017 after spending 56 days in an isolation cell. Following his release, Şansal wrote his second book, titled “Makam Odası — Linç” (Office – Lynch), about his arrest and unjust treatment in the prison. Today, many Turkish nationalists see the 64-year-old fashion designer as a traitor to the Turkish nation, while one said his arrest was a message to other opponents to stop dissent.

Turkish Minute spoke with Şansal, one of many Turkish citizens who have opted to leave Turkey in the face of Erdoğan’s one man-rule after a 2016 coup attempt, which led to a crackdown on critical voices.

Why did you decide to leave Turkey?

Something was wrong after July 15, 2016 — the coup attempt in Turkey. While I couldn’t find any sound or lighting systems for my big productions that week, huge stage and lighting systems were installed in 52 municipalities in Turkey on July 16 for the AKP’s democracy rallies. I was very surprised. How was this accomplished literally overnight?

(People had gathered for “democracy and martyrs” rallies to condemn the failed coup, most of them AKP supporters. Some estimates put the number of rally-goers at 3 million or more. The participants, with Turkish flags, banners and posters, were not only there to support the government in the wake of the military coup but also to protest Turkish preacher Fetullah Gülen, who has lived in self-imposed exile in Pennsylvania since 1999 and had been accused by Erdoğan of masterminding the coup.)

A man was shouting at the rally, “Their property is booty. Take their property, they are all halal [lawful] for you!” Without a trial, without an investigation, people were being targeted by AKP supporters.

The culture of plunder, looting and occupation was resurgent once again in Turkey. This was a breaking point for me; I was very scared that day. Of course, the lynching attempt at the Istanbul airport was also shocking.

After two months in jail, I tried for three more years. Meanwhile, I demanded justice, they had beaten me up and broke my tooth in front of the cameras, and there were many eyewitnesses, but the court “could not find” any concrete evidence in my lynching case. My claim for compensation for pecuniary and non-pecuniary damages was not accepted by the court, so I decided to leave Turkey.

Why did you choose Cyprus?

It was Yıldırım Mayruk’s [Şansal’s mentor and later business partner for the past 32 years] idea. We were in the car on our way home after a party following the 2016 coup attempt, when out of the blue he said: “I feel very tired now, I want to leave and settle in Cyprus. What are you going to do?” I chose to move with him. We bought land, we built our houses. We sold our fixed property and closed our business and severed our roots to Turkey.

Turkey is a very rich country; there are many nationalities, many religions, many cultures, but the state and government were never nice to them. Discrimination and nationalism disgust people, and at some point, they decide to move. We left Turkey last October and are living happily in Kyrenia, northern Cyprus, now.

Do you have business plans in Cyprus?

Yes, we will continue our business here. The island of Cyprus is close to a number of countries; Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Greece and Turkey. We will continue to work, create and set the fashion scene in Cyprus from now on. We also have other goals and plans: We aim to contribute to peace and cultural projects on the island.

If I understand correctly, you find it pointless to stay in a country with no freedom of thought, no security of life or property, even it’s your homeland.

Homeland is not the place where one’s stomach is full, but the place where one’s hopes flourish and grow. I first left Turkey in the early 1980s and stayed abroad for nine years. During those years, I met different people. I had Armenian friends who had to leave Turkey and live abroad. Turkey was very rude to its citizens like my Armenian friends. After a number of years, I chose to return to Turkey, but I won’t this time. There is no security of life, there is no law. There are also other countries that have problems in the area of law, but Turkey’s biggest problem is impunity. There were many murders of journalists whose cases are still unsolved even today. Those who speak out in Turkey are always punished.

When you speak the truth, you experience pressure and censorship in Turkey. In the last few years, the Turkish press began to ignore me, while my interviews appeared in the foreign press. The press of my own country ignored me because my views were not pro-government.

Did you leave Turkey because of the AKP government?

When I was a student at Istanbul’s German high school, I had Armenian, Greek and Jewish friends. Istanbul was a colorful city, we had a multicultural environment, but the Turkish education system lied to us. They made us believe that the Turkish nation was stronger than other nations. They made us believe that we were the most hardworking, most honest, most tolerant, most intelligent people as well as morally superior. This was wrong. The history we were taught was “official-national” history, but over time, I read books, became involved with minority foundations and NGOs and faced the injustices in the real Turkish history.

Therefore I did not keep silent, I spoke out and was almost lynched in the end. I was attacked in Taksim Square 11 years ago, in front of many cameras, and again the perpetrators could not be found. The state is like a god in Turkey, it is a “divine power,” a dogma… When you criticize the state and its policies they accuse you of violating Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code — denigrating Turkishness, the Turkish Republic, the foundation and the institutions of the state. It’s insane.

Were there fundamental problems before the AKP government?

Yes. It was a time of coverup, a “costume play.” They used nail polish, they manicured the bear’s paw, they thought it would fix everything, but when that nail polish wore off, the ugly paw reappeared. The social structure of the society is clear: egotistical, utilitarian, ambivalent and self-interested… We cannot change this society with make-up; we need real policies and progress.

Does it hurt you not to be understood in your homeland? I know you love Turkey.

I loved it, but it didn’t work. I am “divorced” from Turkey [laughing]. You can do nothing when it doesn’t work. I don’t mean to be insulting or rude. I’m still a Turkish citizen, I could become a citizen of an EU country, but I don’t want to. I love Turkey, I wanted a secular and democratic country, I wanted the rule of law in Turkey, that was my struggle.

To be honest, my feelings have disappeared, I neither love nor hate [Turkey]. I have no feelings left for my homeland. Things have made me weary. I still do love Turkey, but I need to feel that my life and my belongings are safe, but the state won’t guarantee my security in Turkey.