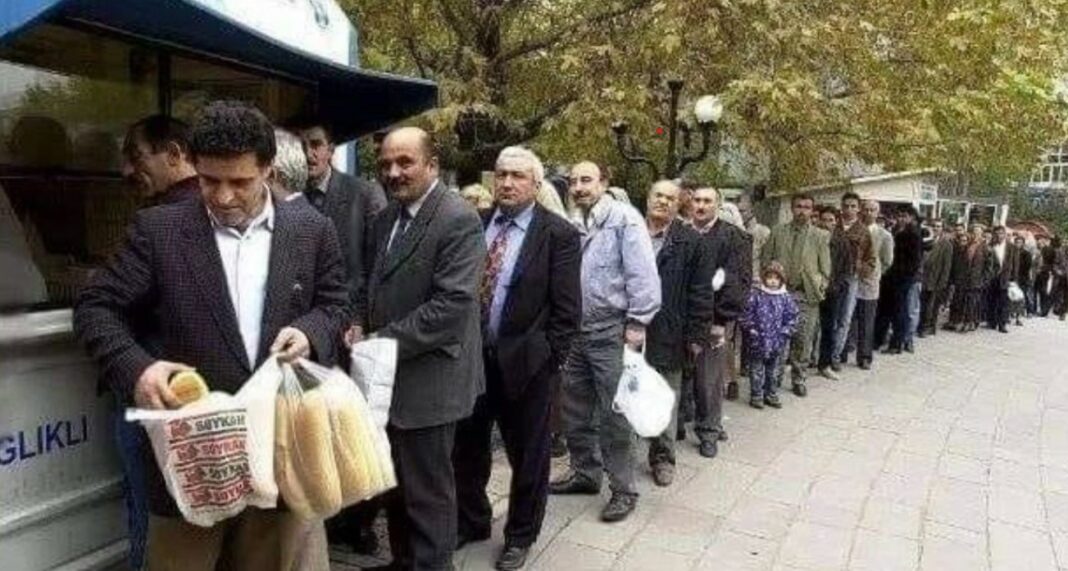

In the early 2000s Turkey went through an economic crisis that served as a catalyst in President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s rise to power. People lining up in long lines to buy cheap bread, one of the major symbols of the crisis at the time, has made a reappearance after 20 years. A low-cost bread factory operated by the İstanbul Municipality increased its production by 50 percent, while ruling party deputy Şahin Tin made national news by saying, “If they are able to get bread, it means they are not hungry,” during a session of parliament.

An economic downturn and the value of the lira, which is hitting record low after record low, coupled with an additional negative impact caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, have rendered the Turks’ financial difficulties visible, most notably with the ever-growing lines at stalls where cheap municipal bread is sold.

In Turkey a 220 gram loaf of bread sells for TL 2 ($ 0.24), while the price of the municipal “People’s Bread” (Halk Ekmek in Turkish) is TL 1 ($ 0.12). The long lines at the stalls are indicative of the growing significance of 12 cents for the budget of a regular Turkish citizen.

Bread is a central and traditional part the Turkish diet. With a daily consumption of 85 million loaves, Turkey holds the world record for bread consumption per capita.

People’s Bread stalls are available in almost all major cities in the country and are run by the municipalities, which is why they can afford to sell bread at lower prices than private bakeries. The İstanbul Metropolitan Municipality (İBB) has three factories and operates hundreds of stalls.

Özgen Nama, board director for İstanbul’s municipal People’s Bread, explained to Deutsche Welle Turkish service the growing demand for their product.

“The reason for the long lines at İstanbul People’s Bread stalls is that the price is half [of what is charged by private bakeries]. This is a demonstration of public impoverishment. Over the past five years our production used stand at a daily average of 800,000 to 900,000 loaves. However, as of November 2020 this has climbed to 1,250,000 loaves,” Nama said.

“Despite our increased capacity, the demand is continually growing and the lines are not getting any shorter.”

Demand has jumped by 50 percent

The capital Ankara is one of the cities where demand for cheap bread is high. From the early morning hours, lines mostly made up of retirees form in front of the stalls. In the Ankara Municipality’s online complaint mailbox, long lines caused by an insufficient supply of bread is one of the most frequent complaints received.

Although municipalities have increased their production capacity, the lines are getting longer, which also became a subject of discussion at the parliament.

Main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) deputy Engin Altay addressed ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) members and said: “Friends, the people are hungry, they are desperate. Yes, their stomachs do get something, they get dry bread,” to which AKP deputy Tin responded, “Then it means that they are not in fact hungry.”

Tin’s remarks prompted widespread outrage on social media as thousands of Facebook and Twitter users posted comments with the title “If the public is able to eat dry bread, it is not hungry.”

Bread lines a symbol of the crisis

The crisis over bread, a staple in Turkey, had also shaken Erdoğan’s government last month. Devlet Bahçeli, leader of the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and an ally of Erdoğan, launched a charity campaign for the poor in which the well-off were supposed to buy extra loaves of bread and leave them in designated locations for the poor to get for free. Bahçeli himself had initiated the campaign and left a bag of bread he had purchased.

Erdoğan’s AKP strongly objected to their ally’s campaign, which was reminiscent of the early 2000s when Turkey was hit by a major financial collapse.

After the crisis, Erdoğan came to power with a strong economic recovery program, making use of the images of long bread lines that symbolized the public trauma. Throughout his 18-year rule, Erdoğan has repeatedly used the photos of the lines at his election rallies, saying, “Do not forget those days.”

After an absence of 20 years, the lines have returned. The factories are unable to meet public demand. In addition to the exchange rate plunging to unprecedentedly low levels against other currencies, the government is being accused of not sufficiently aiding the public amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

75 million credit cards in a country of 82 million

One of the significant indicators of the downturn in the economy is the expanded use of credit cards and an increase in credit card debt. According to November 2020 data provided by the Interbank Card Center (BKM), some 75.3 million credit cards are actively being used in Turkey, a fairly high figure for a country with a population of 82 million.

BKM figures also show that in November 2020 credit card sales stood at TL 90.7 billion ($11.5 billion), corresponding to a 20 percent increase over the same period last year. In the first nine months of this year, private debt to banks grew by 37.2 percent.