Bünyamin Tekin

“The increasingly widespread witch-hunt, systematic and widespread hate speech, ongoing persecution and massacre of Gulen movement members have made conditions in Turkey ripe for a deliberate, planned and systematic genocide,” Bülent Keneş, a veteran Turkish journalist in exile, wrote in his newly released book, which he says attempts to sound the alarm to the international community about developments in Turkey that are inching closer to a full-fledged genocide against the Gülen movement, a faith-based group targeted by the government.

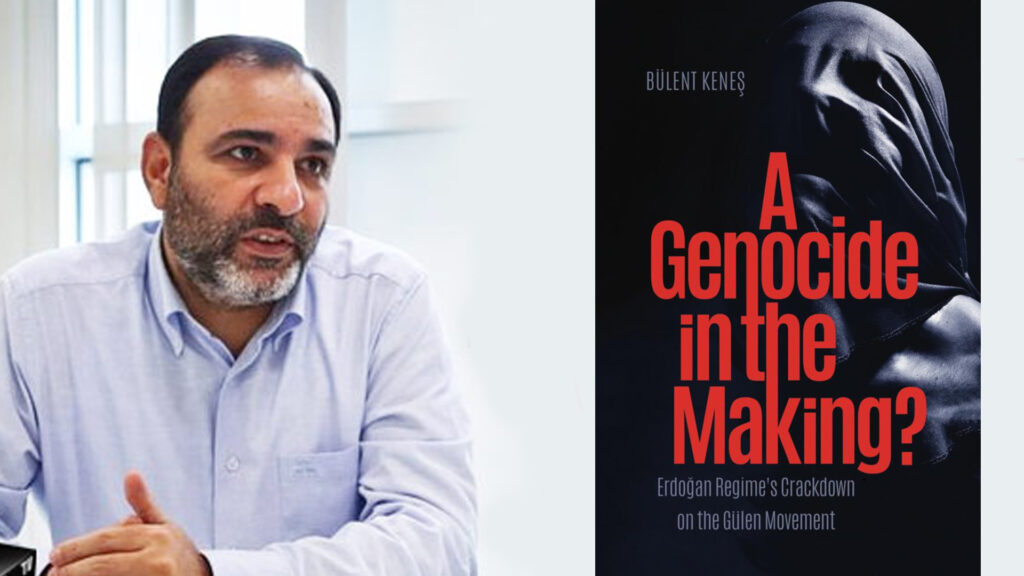

Keneş, who fled persecution in Turkey and has been living in Stockholm for the last four years, spoke to Turkish Minute about his new book, titled “A Genocide in the Making? Erdogan Regime’s Crackdown on the Gülen Movement.”

Having served as the editor-in-chief of Today’s Zaman, an English-language daily, Keneş has catapulted himself to the top of Ankara’s wanted list through his outspoken criticism of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government, which he calls an “Islamofascist regime.”

Today’s Zaman had the highest daily circulation among foreign-language dailies in Turkey. Its sister Turkish daily Zaman was also the most circulated daily in Turkey with over 600,000 subscribers before it was seized and shut down by the Erdoğan administration in 2016.

The veteran journalist currently faces three aggravated life sentences plus 15 years in prison in Turkey over one of his articles.

Those unfamiliar with Turkey’s current affairs would have a hard time understanding how a person in a NATO-member country can face death in a prison cell for writing 500 words. Nonetheless, Turkey-watchers will recall that the country is ranked 154th among 180 countries in Reporters without Borders’ (RSF) “2020 World Press Freedom Index,” behind even Vladimir Putin’s Russia and Alexander Lukashenko’s Belarus.

“The situation with regards to rights and freedoms started to deteriorate in Turkey as early as 2011,” Keneş says, adding that he foresaw the authoritarian future in store for Turkey, to the dismay of optimistic colleagues “who thought Turkey had what it takes to tackle Erdoğan’s drive for power.”

“I was more of a pessimist; I could see that international pressure to keep Turkey along the lines of a democracy would cease to operate after certain thresholds were passed, downgrading the country’s relations with the functioning democracies of the world to transactional ones,” Keneş points out.

Pinpointing the landmark moments in the country’s “descent into fascism,” Keneş says the year 2013 stands out for several reasons.

Populism unhinged

“The downhill trajectory accelerated after countrywide protests in 2013 during which Erdoğan targeted protesters directly, calling them ‘looters,’ and a graft probe that exposed bribery scandals in the highest echelons of government, with possibly incriminating evidence against Ankara’s strongman, who didn’t take it well and lashed out at the judiciary,” according to Keneş, who adds that this is where the Gülen movement takes center stage in Erdoğan’s discourse scapegoating perceived enemies for things that go wrong in the country.

Inspired by Muslim cleric Fethullah Gülen, the Gülen group “is known for its social, cultural and educational activities in Turkey and in nearly 170 countries around the world and was widely appreciated in Turkey,” Keneş writes in his book, citing online sources. He contrasts the movement’s moderate Islamic worldview with Erdoğan’s radical outlook and accusations against him of promoting extremism to hint at the distinctive features of the Gülen group that render it a possible victim of genocide.

What qualifies as genocide?

Keneş characterizes genocide, a nonexistent term prior to 1944, as “the intentional destruction of, in whole or in part, a group that differs from others based on its nationality, ethnicity, race, political view, or religion, in line with a plan and the advantage of the destroyers.”

There is a debate among scholars over which groups might be potential victims of genocide, with some including Stalin’s systematic killing of kulaks and Indonesian dictator Suharto’s mass killings of communists as acts of genocide, and others introducing new terms such as “politicide” to describe those atrocities.

However, Article 6 of the Rome Statute, which defines the crime of genocide as “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group,” excludes groups shaped by political views from the definition.

Is the Gülen movement a religious group?

Keneş in his book identifies the Gülen movement as a socio-religious group with distinctive features.

“Even though the Gülen movement is not a religious denomination,” Keneş notes, “they are branded as heretics by Turkey’s Directorate of Religious Affairs, and the oppressors’ view of the targeted group suffices to make them fall under the scope of the Rome Statute.”

Keneş states that he used the 10 stages formulated by Gregory H. Stanton, a renowned scholar in genocide studies, to assess the likelihood of extermination taking place through a set of criteria.

Stages leading to extermination

According to Keneş, the first stage Stanton mentions was secretly carried out through years of surveillance conducted by the state security apparatus to blacklist Gülen movement members, profiling the group based on various criteria such as a subscription to Zaman, seen as the group’s flagship newspaper, or membership in a professional organization considered to be Gülen-affiliated.

“The aftermath of the graft probe saw Erdoğan openly engage in activities that directly correlate to other stages put forth by Stanton,” Keneş argues, “namely symbolization, discrimination, dehumanization, organization, polarization, preparation and persecution.”

“Erdoğan has argued that the corruption operations were a ‘coup’ to topple his government despite the mounting evidence of wrongdoing,” Keneş says.

“Divorced from reality, he claimed the graft and bribery operations were carried out by police, prosecutors and judges who were close to the Gülen movement, and he embarked on the demolition of state institutions and the judiciary.”

According to Keneş, the symbolization stage was underway as Erdoğan embarked on a campaign to delegitimize the Gülen movement, labeling it an “illegal organization with a legal appearance,” calling it the “Parallel State Structure” and eventually “FETO” – the Fethullahist Terror Organization.

Between 2013 and 2016, Erdoğan prepared the mechanisms that are prerequisites to carrying out genocidal acts, marginalizing people with ties to the group, cementing his rule by appointing cronies to key offices and controlling the media, repeatedly using explicit pseudo-medical and epidemiological metaphors, such as virus and cancer, to dehumanize the group, which sounds the alarm for an imminent genocide, Keneş says, citing scholars of genocide studies and adding, “When the perpetrators dehumanize a certain group, they render it possible to seize their property, torture and rape them, and eventually destroy them.”

“After a failed coup in July 2016, which Erdoğan unsurprisingly accused the Gülen movement of instigating, Turkey took a nosedive in the world with respect to the rule of law, rights and freedoms,” Keneş says, “after which a full-on persecution of the group was launched.”

“More than 130,000 people have been dismissed from their civil service jobs and deprived of their and their families’ subsistence. More than 282,000 people of all ages, because of their daily activities, which are non-criminal acts according to law and part of their normal routine, have been taken into custody, and in excess of 600,000 have been the subject of investigations. At least 77,000 people have been incarcerated.”

He notes that “in excess of 110 — some claim about 200 — media outlets have been closed. Nearly two hundred journalists are still languishing in jail.”

“As far as members of the Gulen movement are concerned, every act that can be performed by an ordinary person in the course of daily life can easily be turned into a crime and thus treated within the scope of the penal code,” Keneş writes in his book. “When exercised by Gulen movement members, the constitutional rightto establish media outlets and thus to publish newspapers, magazines, and books as well as engage in TV and radio broadcasting is simply put into the context of crimes of ‘terrorism’ and ‘treason’ …”

‘Extermination is not a remote possibility’

“Since perpetrators do not see members of the target group as human beings, they prefer to call the process of destruction ‘extermination’ instead of killing. They argue that they ‘cleanse’ by ‘extermination,’ purifying society of disease, animals, viruses, microorganisms, cockroaches, leeches, enemies and traitors,” Keneş’s book states.

“We might have come to this stage,” Keneş argues, saying that if one sticks to the definition put forth by the Rome Statute, waiting for the mass killings to occur would not even be necessary to recognize acts of the Erdoğan regime as genocide.

Pointing out that “the legal definition and description of genocide is not just mass murder,” Keneş emphasizes that it extends to “serious physical or mental/psychological damage to the members of the target group.”

“Well-documented cases of torture, rape, threat of death and sexual assault targeting Gülen movement members because of their group identity” fall under this category, according to Keneş.

Genocide is preventable

On whether it is possible to prevent genocide from happening or not, Keneş says a historic resolution adopted at the United Nations 2005 World Summit stipulates that when sovereign states fail to live up to their responsibility to protect their own citizens from catastrophe, the broader community of states assumes the obligation.

“What we see today in the world is a general tendency to appease authoritarian leaders who are an inch away from committing atrocities, or are already perpetrators of genocidal acts,” Keneş laments, stressing that there are myriad ways to paralyze the likely perpetrators before a military intervention, like the one by NATO in the Kosovo war, becomes the only way out.

“Sanctions can target would-be perpetrators’ ability to move freely in the world, or the financial sources that support them.”

Fighting authoritarianism on a global scale

“As an individual who is targeted by an authoritarian regime, and a first-hand witness of what such a regime is capable of, I cannot do anything but do what I am capable of doing to raise awareness against the global rise of populist authoritarianism,” Keneş says, mentioning the latest project he‘s involved in.

“We are in the final stages of establishing a think tank called the European Center for Populism Studies,” Keneş notes, stating that nearly 50 academics from various countries are already involved in the founding of the center, which will include 10 research programs and will publish two periodical journals. “This research center will strive to highlight ways to contain the rise of authoritarian populism.”

Turkey’s future

“I am a pessimist,” Keneş admits when asked about his view of the future of his home country.

“Turkey’s problems go beyond Erdoğan and politics, and I don’t see an easy way to overcome them any time soon.”

The Early Warning Project, an initiative by the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, ranked Turkey in eighth place among 162 countries for “estimated risk for onset of mass killing in 2018-2019.”

The same initiative put the country in 24th place, immediately above Rwanda, in its 2019-2020 list, still including it in the top 30 countries it deems to be at high risk.

Bülent Keneş, PhD, is an exiled Turkish journalist who has been the author of seven books on Turkish politics, Iran, Islam. A veteran journalist for over 25 years, Keneş is the founding editor-in-chief of the Today’s Zaman, an English daily published in Turkey until 2016 when it was shut down by the government of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. He is also among the founders of Stockholm Center for Freedom (SCF). He is now a member of a team establishing the European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS) in Brussels.