Recent moves by the administration of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan targeting the Kurdish language have signaled a new wave of crackdowns on Kurds in Turkey.

After removing elected Kurdish mayors from office and jailing many of them on terror charges, Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) has stepped up pressure on Kurds by imposing Kurdish language bans in a number of areas.

Despite the fact that it has never been explicitly banned, the Kurdish language was criminalized as separatist starting with the foundation of the Turkish Republic in 1923 until 2002, when the publication of Kurdish texts was legalized in the early days of the AKP government. However, the latest practices imply to many that the AKP has adopted the brutal old state repression towards the use of Kurdish, which has again become a basis for charging Kurds with disseminating terrorist propaganda, notably since a failed coup in July 2016.

Many critics argue that Erdoğan started taking back the rights given to the Kurds in the early days of his administration when he realized in 2015 that he could not achieve his presidential dreams through then-ongoing peace talks. Selahattin Demirtaş, former leader of the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), was the first political leader to focus on Erdoğan’s increasingly authoritarian tendencies and at the time promoted the election rally slogan “We will not make you president.”

In reaction to a recent ban on play in Kurdish, Ali Babacan, leader of the Democracy and Progress Party (DEVA) and a former AKP economy minister, said Turkey was relapsing into the mindset of the 1990s.

“Kurdish is the native language of our Kurdish citizens. We had solved such kinds of problems in Turkey’s most brilliant period [during the AKP’s early years in office]. Nobody can dare drag Turkey back to the 1990s. A governing approach that fears a language used by its own citizens cannot be acceptable,” Babacan said on Wednesday.

The most recent incident took place in Istanbul’s Gaziosmanpaşa district where a governor on Tuesday banned the performance of a Kurdish-language rendition of an Italian play at the İstanbul Metropolitan Municipality (İBB)’s Istanbul City Theatre. It would have been the first Kurdish play to be staged at the state-owned theatre in its 106-year history.

The governor said in his notice that the Kurdish rendition of Italian playwright Dario Fo’s “Trumpets and Raspberries” might “disturb the public order.”

The ban was interpreted by critics as a message to both the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), which has run the İBB since last year, and the pro-Kurdish HDP, which is accused by the AKP of having connections to the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a Kurdish group designated by Ankara as a terrorist organization as it has waged a separatist insurgency against the Turkish state since 1984.

In the 2019 local elections in İstanbul, the HDP did not nominate any candidate and backed the CHP’s Ekrem Imamoğlu against the candidate from Erdoğan’s AKP.

The Kurdish play was first targeted by the Aydınlık newspaper, owned by the left-nationalist Patriotic Party (VP) led by Doğu Perinçek, a staunchly secular, anti-Western political figure. The daily published news on October 5 titled “İBB’s stage serves PKK’s theatre group.”

Ironically, VP leader Perinçek is known for praising Abdullah Ocalan, the jailed leader of the PKK, many times in the 1990s. Perinçek, who is characterized by his onetime friend, history professor Halil Berktay, as a “a passionate person who pursues power and influence,” was a Maoist until the 1990s before becoming pro-PKK. He has finally shifted toward Kemalism, Turkey’s official ideology, stressing its nationalist, secularist and anti-imperialist stance. Lately, Perinçek has created a new alliance with his former arch-enemy, Erdoğan.

However, Perinçek recently reiterated his “never changing” stance, saying: “Erdoğan has come to us [our ideology, our policies]. We have not gone to him [Erdoğan’s policies].”

In October of last year, seven members of Kurdish musical group Dewran were arrested on allegations of spreading terrorist propaganda in the Viranşehir district of Urfa province. The group was singing at weddings not only in Kurdish but also in Arabic at the request of guests. The singers were held responsible for attendees dancing and waving pieces of material in red, yellow and green, colors that allegedly represent the PKK.

Turkey’s Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK) in 2018 ordered a television station to halt broadcasting five times and handed down a fine on the grounds that it “disseminated propaganda for an armed terrorist organization.” During a program on Yaşam TV, a guest had given a greeting in Kurdish and sang a song in Kurdish.

In 2018 a Kurdish TV channel for children, Zarok TV, faced the same punishment based on the same charge of “promoting terrorism” since it aired a song mentioning “Kurdistan,” or “country of Kurds.” At the time, the Turkish broadcasting watchdog said in its notice that positive references to a “so-called Kurdistan” served the PKK’s interests.

In the same year the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT), Turkey’s state broadcaster, banned 66 Kurdish songs as they supposedly “propagated terrorism.” However, the list of banned songs included those of Kurdish singer Rojda, which were played by TRT on the radio and on TV for years. Blacklisting songs on the grounds of spreading political propaganda was an old TRT practice dating back to the 1980s following a military coup. TRT was criticized at the time that it was wasting the country’s time with such kinds of “backward actions.”

In May 2018 the print, distribution and sale of nine books published by prominent Kurdish publishing house Avesta were banned and existing copies were seized.

Bans on the Kurdish language have even been adopted by private pro-Erdoğan entities. İstanbul Commerce University dismissed a history professor on August 31 as he gave an assignment to his students to translate into Kurdish the Turkish National Anthem and “Address to Youth” penned by the Turkish Republic’s founder, Kemal Atatürk.

“The university, which should be an institution of critical thinking, has interpreted my assignment as separatist propaganda. If we can speak German, Arabic, Farsi and English at the university, then why not Kurdish?” Professor Bekir Tank wrote in a column in the DoğruHaber newspaper in reaction to the university.

The first official act of AKP-appointed trustees who have replaced the majority of elected Kurdish mayors due to alleged terror links was to remove Kurdish street signs installed in Kurdish cities.

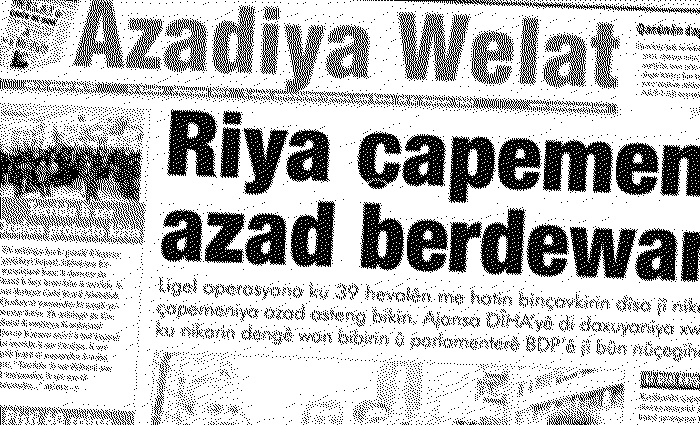

Following the attempted coup, the AKP government shut down a number of Kurdish language institutes, dailies, websites and TV channels as part of a crackdown targeting the Kurdish political movement.