The latest polls show that the opposition’s candidate, Ekrem İmamoğlu, will probably be the winner of Sunday’s İstanbul mayoral election. It will be the second time, but this time, everyone expects more consequences.

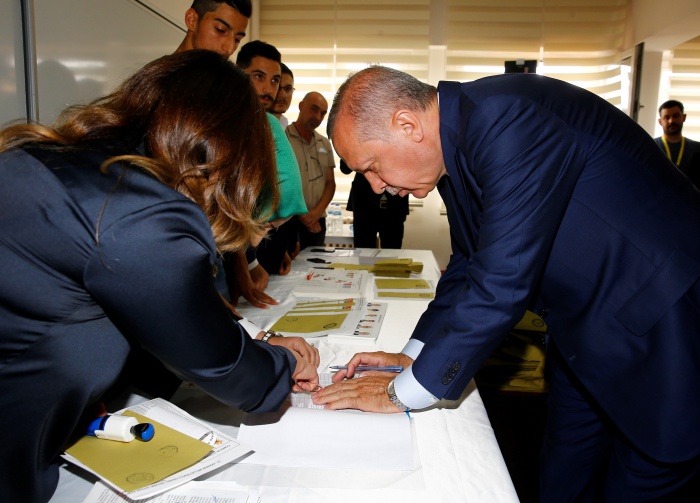

The March 31 local elections created a power vacuum in President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s long rule. For the first time he encountered a popular backlash that led to big losses in Turkey’s major cities of İstanbul, Ankara, Antalya and Adana.

Even though his ruling Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) alliance with a right-wing nationalist party managed to garner over 50 percent of the vote in general, poor economic performance was punished in urban areas.

The cancellation of the İstanbul election results was just another sign of Erdoğan’s corrupt rule, but also a big gamble that would backfire. Surveys indicate that a majority of the public either did not understand the reasons behind the cancellation or were enraged because of it. According to Turkish media reports, even Binali Yıldırım, the AKP candidate, had opposed the idea of a repeat election.

There has been no sign of recovery in the country’s economy since March. A diplomatic crisis with the US over the purchase of Russian missiles made it even worse. US sanctions on Iran’s energy exports hit Turkey hard. Tensions with Cyprus and Greece in the eastern Mediterranean escalate by the day, with the possibility of jeopardizing relations with European countries. Moscow has driven Ankara into a corner in Syria’s Idlib region, undermining its credibility with the armed Syrian opposition.

The public polls are so negative that Erdoğan felt the need to hold rallies for his party, despite his initial decision to stay in the background behind the AKP’s candidate, whose campaign was milder in tone and more focused on municipal projects rather than making it a matter of life and death.

So this is a rare and bizarre period for observers, who expected more from a corrupt authoritarian leader. Has he lost all his power? Will he pull something out of the hat before it’s too late?

In the last week of campaigning, Erdoğan returned to his old tactics. In the latest rallies he capitalized on the unexpected death of Egypt’s ousted leader in court. He told his constituency that the opposition is similar to Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who overthrew the government of Mohamed Morsi, killed thousands and put former government officials on trial.

Bear in mind that before the March elections, Erdoğan used video footage of the mosque shooting in New Zealand to electrify his supporters.

Yesterday, a letter written by the jailed leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) terrorist group was unearthed by a Kurdish academic. The letter contained a message from Abdullah Öcalan, who has called on Kurds to stay away from the opposition in Sunday’s vote.

It’s in clear contradiction of the Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party’s (HDP) decision to fully support İmamoğlu. Since the Kurdish vote is fairly decisive in İstanbul, Öcalan’s letter is actually seen as a move by Erdoğan, who on a TV show yesterday claimed that Öcalan and the HDP are not on the same page.

No one knows exactly what Öcalan really had in mind. But we know that three factors will be more important than others on Sunday: (1) The impact of the cancellation of the İstanbul election results on İstanbul voters; (2) The number of people who will change their decision to vote or not vote; and (3) Erdoğan’s performance last week.

Whatever the outcome, the post-election scenarios formulated before March 31 are still on the table, though. Some observers expect a snap election in the event of an opposition win, which may trigger heavy pressure from the public for change. But more likely we’ll see Erdoğan and his party undermining opposition mayors Ekrem İmamoğlu in İstanbul and Mansur Yavaş in Ankara.

Erdoğan recently signaled that if İmamoğlu gets lengthy jail sentence over an alleged insult to a governor, he would be forced out of office by the judiciary. Just like what happened to Erdoğan in 1997.

A small number of observers, on the other hand, foresee a milder tone in Erdoğan’s one-man rule after the election since he still needs to fix the economy and has to strike a balance between Russia and Turkey’s Western allies. But he still must reassure his allies that he’s the only powerful man in Turkey, after the faltering public support. Therefore, the post-election period could see the start of some unorthodox moves from Erdoğan’s side.

Elections have been neither free nor fair in Turkey for a long time. The ruling party controls the majority of media outlets, Erdoğan still has enormous reach. But if he keeps losing alliances inside and outside the country at that pace, he’ll soon end up being either a ruthless tyrant with minority public support and rogue powers, or just another ousted strongman.