Ekrem Dumanlı

Those who could afford a legal battle against Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s post-coup crackdown knocked on the doors of the country’s Constitutional Court (AYM) after they were turned down by the local courts. However, one could expect that Turkey’s top court would not be impartial in these cases since two of its members were arrested immediately after a foiled coup attempt on July 15, 2016.

As a matter of fact, the chairperson of the AYM, Zühtü Arslan, was complaining about the overwhelming number of cases they had received after the coup. The top court, therefore, ignored tens of thousands of applications from victims of a post-coup purge, who were mostly, allegedly, affiliated with the Gülen movement, which was accused by the Turkish government of orchestrating the coup.

In October 2016, the AYM rejected an application submitted by the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) concerning the unconstitutionality of state of emergency decrees, amounting to the fact that the top court of the land admitted its non-functionality in terms of exhaustion of domestic remedies for cases relevant to those decrees. Thus, victims turned to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), which received more than 10,000 applications from Turkey in a short period of time. In 2017 applications to the ECtHR exceeded 31,500, while they had numbered around 12,600 the previous year.

Admitting that it could not handle the thousands of new cases waiting to be assessed, the ECtHR made a surprise proposal to the Turkish government at the end of 2016. Secretary-General of the Council of Europe (CoE) Thorbjørn Jagland held a meeting with then-Justice Minister Bekir Bozdağ in Ankara, suggesting the formation of a commission that would examine the cases sent to the ECtHR related to state of emergency decrees.

This advice apparently served the purposes of both the ECtHR and the Turkish government. The ECtHR got rid of the piles of cases from Turkey, while the government avoided a top European court ruling saying that Turkey had violated certain rights. A few months later, 30,063 applications from Turkey were returned by the ECtHR.

What about the State of Emergency (OHAL) Commission?

Actually the commission proposed by the CoE was a brilliant idea in theory. No one would want to wait for years at the doors of the ECtHR to finally see the face of justice. An impartial and independent commission inside Turkey could resolve the unjust treatment suffered during OHAL.

There was already an example of such a commission, the Terrorism Victims Commission, which was established in 2004 to examine the cases of victims of Turkey’s counterterrorism operations conducted during the 1990s. This commission was created after thousands of applications arrived at the ECtHR. By 2011, the commission had received more than 360,000 complaints and finalized almost 230,000 of them. The government paid around €1 billion in compensation for some 133,000 Turkish citizens.

However the intention of the government was important. In the formation of the OHAL commission, as one might expect, something went very wrong. The first mistake was the appointment of certain public servants who were responsible for the preparation of OHAL decrees in first place. Secondly, the head of the commission, Selahattin Menteş, who also worked for the Justice Ministry, admitted in a newspaper interview that the criteria for dismissing civil servants by OHAL decrees over Gülen links were depositing money in a certain bank, using a certain smart-phone application, enrollment in Gülen-linked schools and membership in certain unions, which should not have been considered “crimes” according to the European Convention on Human Rights.

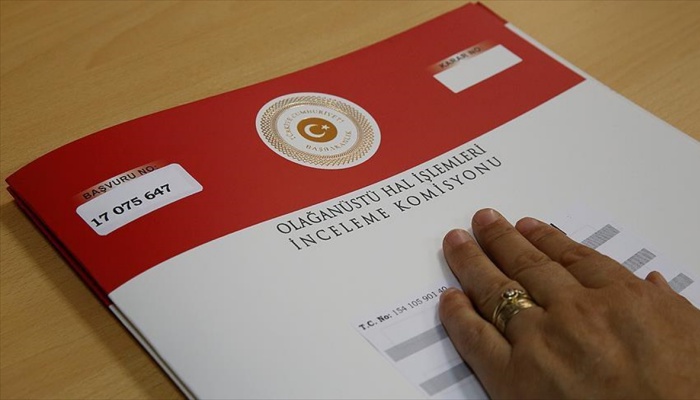

Still, the victims applied to the commission, since the ECtHR left them no choice. As of July, the commission had received some 108,660 applications. Only 30,000 of them had been discussed and 28,100 were rejected.

The Terrorism Victims Commission was established due to the fact that the Turkish state had treated its citizens unjustly and, despite all its shortcomings, had compensated thousands of victims. The purpose of this new commission, however, was not to solve the problems but instead to obstruct the means of claiming rights through international tribunals.

Moreover, the Turkish authorities decided to reinstate civil servants who were acquitted by the OHAL commission to positions that were entirely different from their previous jobs. By doing so, the regime shaped by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan secured its future, keeping partisan public officials inside critical institutions such as the military, the police and the judiciary.

A lifelong struggle

According to the law, a victim whose application is rejected by the OHAL Commission can appeal to the 19th or 20th Ankara Administrative Courts within 60 days. If these courts reject the appeal, then the case can be brought to the Council of State and then the Constitutional Court. If Turkey’s top court finally rejects the appeal, only then can the victim apply to the ECtHR. We are talking about a period of time that can extend to as long as 10 years.

Considering the ECtHR’s pace in discussing cases waiting in line, which can take 10 years for each, the legal struggle of more than 140,000 victims of OHAL decrees, who were dismissed by the Erdoğan regime in a minute, will cost them 20 years of their lives. In the meantime, some victims will have died, or forsaken his or her fight for their rights, or tired of all the procedures, or missed the prescribed deadlines. In short it seems the ECtHR has saved itself a huge amount of work. After 20 years, almost all the victims will have reached the age of retirement.

The reckless stance of the Council of Europe

That’s how effective the solution was that was invented by the CoE and the Turkish government! Of course, those who paved the way for such a legal charade by trampling the values of the CoE will not escape history’s judgment. CoE officials should have known that the Turkish government, which caused the unlawful treatment in the first place, would not change its ways and return to the law. As I mentioned in the previous article, they apparently did not want to strain relations with Turkey by keeping human rights violations on the agenda all the time, which could have caused them to lose their “gains.”

The Council of Europe and the ECtHR should stop political negotiations and cooperation with authoritarian regimes and behave in accordance with their values. While mentioning that without contributions from Russia and Turkey, the council could only afford to work until the end of 2019, if only the secretary-general of the CoE, Thorbjørn Jagland, had also spoken about what he had done to stop human rights abuses in these countries.

Why has the ECtHR judge from Turkey, Işıl Karakaş, remained silent?

Professor Işıl Karakaş, who has represented Turkey as a judge at the ECtHR since 2008, was also the co-chairperson of the top European court for a while. Although her tenure ended in April 2017, she has remained in her position since the ECtHR rejected possible candidates offered by the Turkish government to replace her, underlining their inadequacies. The government, which would love to make this a case for its anti-European rhetoric, has somehow accepted the situation. I suppose the recent performance of Karakaş, who I think deserves her position more than anyone else in the country, has satisfied the Turkish government. According to an interview she gave to the Hürriyet daily last year, she was content with the OHAL commission solution.

Işıl Karakaş, as an invaluable jurist, was unfortunately concerned about management of the court’s workload instead of worrying about the implementation of the European Convention on Human Rights and the values the ECtHR would uphold. However, she should strive to make sure the OHAL Commission works in line with universal law, not political criteria, a struggle that would make her a symbol of human rights and universal values. I wonder how she faced the reality that the cases of journalists Şahin Alpay and Mehmet Altan were speedily resolved at the ECtHR on her watch, while the applications of Hidayet Karaca and Mustafa Ünal, whose cases were quite similar, have been ignored for all these years.