[avatar user=”mefecaman” size=”medium” align=”left” link=”file” /]

OPINION | MEHMET EFE ÇAMAN

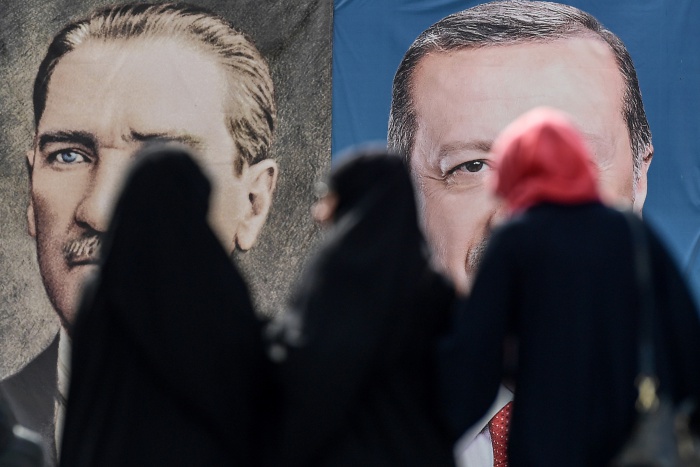

It is hard for me to believe what is going on in Turkey nowadays. Turkey used to be a country that was negotiating with the European Union, a NATO member and part of the West since the end of World War II. With an undeniable experience of democratization and transformation since at least the Edict of Gulhane in 1839 and particularly the First Constitutional Era of 1876, Turkey has a long history of constitutional democracy and individual rights. Yet, for the last couple of years we have witnessed what is unquestionably the most extensive purge in modern Turkish history, which has included military coups. This unprecedented persecution is derived from a set of factors, most of which are linked to Turkey’s political history.

Historically, the Turkish state has been very strong. This has manifested itself through constitutions that provided for a centralized system of governance. Yet the institutional architecture of the state included constitutional thinking that embraced concepts such as the rule of law, representative institutions, free and fair elections, modern legal systems and increasing political freedoms. The level of democracy in Turkey in 2006 presents an example of how the deep penetration of political modernization, a sophisticated organization of the state architecture, especially in terms of separation of powers and its manifestation in the constitutional design, promoted a certain basis for further democratization. Ankara’s EU integration policy was able to implement comprehensive reforms because of this constitutional and institutional framework as well as the existence of the motivation for the Europeanization and democratization of the country. Erdogan and the AKP recognized it and deliberately integrated a systemic transformation policy into their program. Technically (on paper) Turkey became a democracy. However, in the EU-adaptation process the systemic protective elements of Turkey’s political system, particularly the role of the military in the veto regime – a concept used by William Hale to describe the military’s superiority in the Turkish political system – in which the military de facto had the last word in the political decision-making process for all vital questions, had to be removed. A significant part of the military accepted the “demilitarization of the political sphere” since they considered this step relevant for Turkey’s further democratic improvement on the way to EU membership.

Nevertheless, there were also officers who disagreed with the optimism of their colleagues who supported this influential change. This particular group in the Turkish military, who blamed the EU for the extensive democratization and its result – the power shift – knew they were losing all their privileges, power and influence in this democratization process. They refused to accept the reality that they were now the underdogs in Turkish politics. They perceived the Islamist AKP and its then-allies (the Hizmet Movement, liberals, Kurds, leftists, etc.) as a direct threat to their interests. They kept these personal motives under the ideological hat of Kemalism. According to this Kemalist perception, Islamists and Kurds were the “others” and should be excluded by the system. Besides, they mistrusted the EU and the West – particularly the US – because of their relative support for the then-pro-Western and pro-democracy AKP and their positive and supportive position towards the Kurds, since due to democratization the Kurds had gained more rights and gradually became more persuasive in Turkish politics. The AKP was pursuing a reasonably liberal Kurdish policy, officially conducting negotiations – the so-called “solution process” – with the PKK and its imprisoned leader Ocalan to end the long-standing bloody conflict.

This equation in Turkish politics, however, was shaken and broke down when a corruption scandal occurred in December 2013 in which high-ranking politicians and bureaucrats from Erdogan’s closest circle were involved. A criminal investigation took place and 52 people were detained, among them Iranian businessman Reza Zarrab and the director of the state-owned Halkbank. Erdogan blamed the investigation on an international plot (US and German) and promised payback to the Hizmet Movement as the so-called “instrument” of this international plot. The government sacked prosecutors in the investigation and numerous high-ranking police chiefs and changed the procedural regulations in the police force, forcing officers to inform their superiors of their investigations in order to stop potentially ongoing similar corruption investigations. Moreover, Erdogan increased his control over Turkish public and private media outlets in order to spread his manipulative narrative (international conspiracy, “parallel state,” “civilian coup attempt against the elected government,” etc.). In fact, he intervened in the ongoing judicial process to protect himself and his circle of power before justice. He thereby violated the constitution and destroyed the constitutional order, extended his power and seized the power of justice. Nevertheless, Erdogan had only a temporary solution and still felt quite insecure since he was not yet omnipotent. There were still other influential forces and a relatively free media to take care of. They were able to turn everything upside-down, and he could find himself removed from power and sitting in front of the Supreme State Council. The trickiest and most essential detail in this power constellation was a newborn alliance, a game changer, between Erdogan and the anti-Western faction in the military. The unhappy but still mighty underdogs made their doomed old Islamist but corrupt and vulnerable enemy an offer he couldn’t refuse: immunity! In return, they demanded their old status in the system with all their privileges, including the revival of the Turkish deep state. Erdogan had no choice but to agree to this “small price.”

As a result of this diabolical, Machiavellian partnership, all cards in Turkish politics got shuffled once again. Erdogan abandoned all his former partners – liberals, Kurds, his Islamic brothers from the Hizmet Movement, the EU and even the US. The deep state that was reborn from the ashes easily obtained control in key policy areas. They therefore managed to stop the negotiations with Kurds and launched a hawkish new military strategy in the Kurdish issue; they also demonized the Hizmet Movement and initiated a radical shift in Turkish foreign and security policy. Erdogan ended the moderate course with the Kurds and ordered a heavy military offensive in villages, towns and cities. As a result, tens of thousands of people left their homes, and entire towns and neighborhoods in Kurdish cities were completely destroyed. Numerous institutions and people affiliated with the Hizmet Movement were purged, their schools, universities and media outlets plundered and seized without legal basis, and more importantly, their private properties were unlawfully confiscated. Foreign and security policy was the breaking point. Due to the fact that the deep state-affiliated wing of the military is the pro-Russian Eurasianists, who intend to minimize Turkey’s role in the Western alliance and want to generate a strategic partnership with Russia and its partners (mainly Iran), they changed Turkey’s policy in Syria.

After a military coup attempt (July 15th, 2016) Erdogan jailed about half of all admirals and generals in the Turkish military and significant numbers of officers. It is no secret that most of the purged officers were pro-Western and pro-NATO commanders who disagreed with the pro-Russian imaginings of the Eurasianists. There are considerable factors indicating that the extensive purge after the coup attempt was a politically motivated process of liquidation. In this complicated power game, Erdogan seems to be just a component of a greater political coalition in which he does not have absolute control, even though he is going to be the only one who will be blamed if something gets out of control (for example as a result of an economic crisis). Due to the thick political fog, the components of this power concentration behind the scenes is still not fully visible – yet, we can recognize its contours and blurred shape due to numerous indicators that we can not and should not ignore.

In conclusion, what we have in Turkey right now is that principally the separation of powers – the fundament of the rule of law and the most significant main pillar of the Turkish constitutional state architecture – no longer exists due to the state of emergency regime. The constitution now exists only on paper. As a consequence, previously existing constitutional checks and balances have disappeared. The political system we are dealing with has nothing to do with the state design that was created by the constitution and with the practices we observed in the past. The parliament has lost its ability to make laws and to fulfill its oversight functions. The opposition is paralyzed and in a deep coma. Tens of Kurdish MPs are in jail, including the leader of the HDP, Selahattin Demirtas. Some 150,000 dissidents have been taken into custody since July 2016, and 78,000 have been arrested. Over 150,000 public servants lost their jobs on the basis of fabricated accusations and without court decisions. Hundreds of journalists are in jail. And under these circumstances, Turkey is going to “elections”! Is there any hope for change?