Abdullah Bozkurt

Although the Turkish government brags about how it has spent $30 billion on refugees, which many believe to be an inflated figure, it has been unashamedly milking fees under tax and customs schemes from humanitarian aid funds that have been provided by the United Nations.

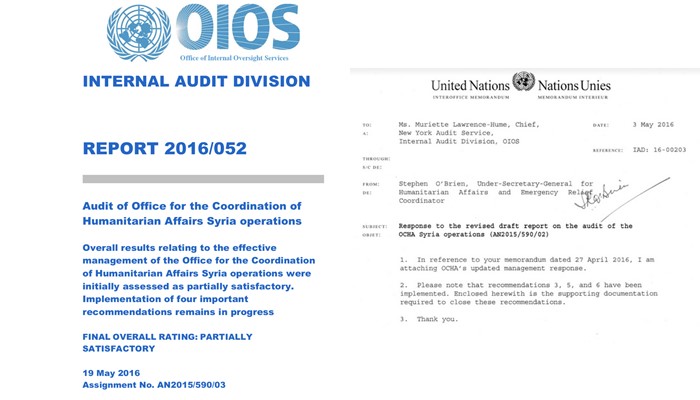

This rather disturbing practice of unjustly taxing aid funds that were destined for millions of the needy in Turkey was revealed in audit documents prepared by the United Nation’s Office of Internal Oversight Services. At the recommendation of the auditors, the UN office signed two agreements with the Turkish government to waive taxes and customs fees on the aid, but the government has delayed adopting one for three years while letting the other linger on the parliamentary agenda without any action on it in the plenary.

Considering that the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has full control of the rubberstamping Parliament and can push laws through the relevant commissions and floor debates in days, the deliberate sandbagging of these agreements to prevent them from becoming part of Turkish law is rather mind-boggling. It also says a lot about why Erdoğan keeps complaining about EU and UN funds not going directly to his government but are instead linked to projects that were designed to help refugees. He even said on one occasion that there is no need to develop projects for the money to be released when his government is doing all the projects that are needed.

At the core of the problem is the peculiar approach adopted by the Turkish government that requires that all UN entities present in Turkey have a separate host country agreement. In other words, each and every UN body has to negotiate and sign a separate agreement in order to not only operate but also to enjoy the immunities and privileges that are part of host country agreements. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), which manages funds, did not have one in Turkey as it is covered by UN Development Programme (UNDP) host country agreements in many member states. But obviously not in Turkey.

Therefore, the OCHA office in Turkey’s border province of Gaziantep on the Syrian border was not covered by the UNDP host country agreement, and the Turkish government refused to extend tax exemptions and other privileges to the office. According to the report from the audit of the OCHA Syria operations, this had cost the UN some $400,000 in taxes between 2013 and 2015 at a rate of 18 percent. This is outrageous as the money needed for some three-and-a-half million refugees, mostly Syrians, in Turkey should not have been taxed in the first place.

The OCHA Gaziantep office was formally set up after a deal was negotiated between the OCHA and the Turkish Foreign Ministry to establish a country office in Turkey. Although the OCHA was already operating as part of the UNDP before the agreement was put in place, the agreement was needed to make it official. It was agreed that the OCHA’s main office would be set up in Ankara, but the OCHA was allowed to set up field offices with the approval of the Turkish government. The agreement was signed by Erdoğan Şerif İşcan, then the director general of multilateral political affairs at the Foreign Ministry and now Turkey’s ambassador to the Council of Europe, and John Ging, director of operations at the OCHA’s Coordination and Response Division in Ankara, on Oct. 3, 2013.

Even with delayed action on the agreement in Parliament, the government has misgivings about the deal. During deliberations at the parliamentary Commission on Foreign Relations on Dec. 17, 2015, Levent Murat Burhan, then the deputy undersecretary of the Foreign Ministry and now Turkey’s ambassador in Dublin, told lawmakers that Turkey would decide where the OHCA could open new branches and underlined that the closure of OHCA offices would be possible if the Turkish government were to decide to do so. Interestingly enough, before allowing the OCGHA operate legally, the government was talking about the closure of its offices. Although Article 7 of the agreement covered taxation issues to some extent, it did not provide all the assurances required by UN auditors to stop the wasting of aid funds. In any case, the agreement was not put into effect until it was approved by Parliament on May 11, 2016 and published in the Official Gazette on May 20, 2016, almost three years after the deal was signed.

Since the tax and customs fees and other financial and bureaucratic hurdles in moving aid for the UN agency were not fully resolved, the UN pushed for a new deal to address issues raised by the auditors of UN expenditures. Hence, the negotiations between the UN and the Turkish government on a set of measures to expedite the import, export and transit of relief consignments and the possessions of relief personnel in the event of disasters and emergencies were completed in December 2015. The formal agreement was signed on June 7, 2016 in Ankara by Cenap Aşçı, then-undersecretary of the Ministry of Trade and Customs, and Kamal Malhotra, the UNDP resident representative acting on behalf of the OHCA. With this agreement, Turkey waived any taxes and fees on the export, import and transit of aid goods.

The agreement was approved by the parliamentary Commission for Foreign Relations on Feb. 8, 2017 but has not yet been debated in the plenary. The Erdoğan government is again using delay tactics for the approval of the agreement although it has the power to push it through very quickly. The last time the agreement was brought to the agenda on the floor of Parliament was on Dec. 6, 2017, when both government representatives and commission members were absent to prevent deliberations on the UN deal. The main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) also was opposed to the agreement, citing Article 2 of the agreement, which stated that the agreement covered not only UN agencies but also governmental, intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations that were certified by the UN within the framework of relief operations.

The CHP argued that the agreement is vague in defining intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations and objected to what it claimed was the removal of the discretionary powers of the government when it comes to regulating these organizations. Although the main opposition party’s stance is understandable from an obstructionist viewpoint, the government is obligated to comply with the relevant provisions of General Assembly Resolution 46/182, which was designed to strengthen the UN’s response to complex emergencies and natural disasters. Resolution 46/182, which was adopted in 1991, led the UN to develop special emergency rules and procedures to enable all organizations to disburse emergency funds quickly and to procure emergency supplies and equipment as well as recruit emergency staff.

The apprehension and anxiety in the Erdoğan government when it comes to working with aid agencies including the UN stems from several factors. For one, Erdoğan has never liked or believed in accountability or transparency in governance. The weakening of the power of the Council of Accounts, the accounting office that audits government expenditures, is the hallmark of his government’s actions since 2013. Despite repeated calls by main opposition leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, who asked the government to disclose where exactly the stated $30 billion expenditures for refugees were spent, Erdoğan avoided furnishing a detailed response to that. Secondly, Erdoğan wanted to channel foreign aid funds to his associates and to amass more power by enriching the patronage system he has built to sustain his regime. Third, most funds provided by the Turkish government have so far gone to Islamist groups, some radical and jihadist-minded ones, for training and indoctrinating refugees so that they can continue fighting Erdoğan’s dirty proxy wars in Turkey’s neighborhood.

I think both the UN and the EU have realized Erdoğan’s motivations in aid schemes and have deliberately channeled them through respectable and trusted agencies in line with auditing standards. A frustrated Erdoğan responded by not only making it difficult for them to operate on Turkish soil, but in some cases, he went as far as to crack down on leading charity organizations that were operating in support of Syrian refugees. For example, in March and April 2017, the Turkish government expelled Mercy Corps and the International Medical Corps from the country, forcing them to relocate their operations to Jordan and Iraq. It is clear from the obstructionist approach by his government that Erdoğan wants to realize his own Islamist pet projects for refugees and does not want anybody to spoil his dream. For Erdoğan, all these intergovernmental and nongovernmental relief organizations are nothing but a nuisance, and he will not put up with them unless he is forced to.