by Abdullah Bozkurt

The primary reason why Turkey’s autocratic president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his associates target human rights defenders by bringing absurd terrorism and espionage charges is to undermine their credibility, discredit their invaluable work in exposing massive human rights violations and intimidate them into silence.

The alarming reports issued by Amnesty International (AI) and Human Rights Watch (HRW) as well as other advocacy and monitoring groups on the terrible record of violations in Turkey under Erdoğan’s leadership have put the country’s rulers on the defensive and raised serious questions over the government’s official narrative.

It was no coincidence that the Turkish government moved in to detain and later officially arrest Taner Kılıç, chair of the board of Amnesty’s Turkey branch, around the time Amnesty submitted a highly critical statement to the UN asking the UN Human Rights Council to exert pressure on Turkey to take steps to address rights violations that have gone from bad to worse. Amnesty highlighted arbitrary detentions and torture, mass dismissals without due process and a massive crackdown on media freedom. On June 8, 2017, the UN secretary-general circulated this letter as an official document to the UN Human Rights Council.

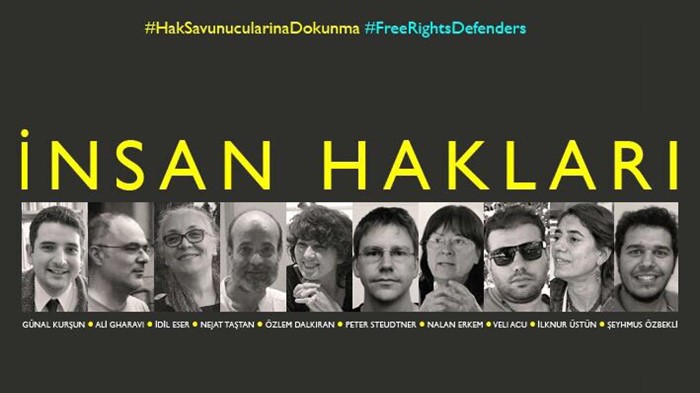

Erdoğan government did not stop there. On July 5, 2017, police raided a workshop on Istanbul’s Büyükada, detaining leading human rights defenders who included İdil Eser, director of Amnesty International Turkey; İlknur Üstün of the Women’s Coalition; Günal Kurşun of the Human Rights Agenda Association; Nalan Erkem of the Citizens Assembly; Nejat Taştan of the Equal Rights Watch Association; Özlem Dalkıran of the Citizens Assembly; lawyer Şeyhmuz Özbekli; and Veli Acu of the Human Rights Agenda Association. Two foreign nationals, Ali Gharavi of Sweden, who specializes IT strategy, and Peter Steudtner of Germany, who is a non-violence and wellbeing trainer, were also detained.

When the fabricated charges that were brought against these human rights defenders and trainers did not make any sense, Erdoğan’s propaganda machine kicked in with a smear campaign accusing these prominent figures of involvement in a plot to take down the Turkish government at the behest of the West. The campaign of demonization followed the same pattern we have started to see in the last couple of years of the Erdoğan regime, which adopted a vicious no-holds-barred approach to defame and dehumanize critics, opponents and dissidents. No doubt the members of the Gülen movement bear the brunt of this witch-hunt by Erdoğan, but others in the Kurdish political movement, Alevis and the secularist opposition received their share of a beating from the Islamist rulers in Turkey.

Under this climate of fear and relentless persecution of critics with the blatant abuse of the criminal justice system, many human rights defenders remain fearful of the next wave of arrests. Erdoğan, who tightly controls the judiciary, swings the politically motivated prosecutions as the sword of Damocles over the heads of human rights defenders.

Therefore, many are distracted by this very serious threat of imprisonment and find themselves in a difficult position to focus on what they have been doing in monitoring and documenting rights violations from the ground in Turkey. In other words, Erdoğan keeps them busy by putting the leading human rights defenders in the line of fire and thwarts their work.

Another motivation for why Erdoğan took the huge risk of inviting the wrath of world community, especially on the eve of the G20 summit in Hamburg, is that he is more worried about the prospect of the mobilization of opposition groups on the home front than risking becoming an international pariah. He has seen how the main opposition political party was able to seize the moment with its March of Justice and gather millions of disenfranchised people at a major rally in Istanbul.

By jailing prominent human rights defenders, Erdoğan is effectively telling Turks that he can come down hard on the opposition if he wants to, thereby reducing their motivation and hampering the ability of dissident groups to mobilize against his rule. In fact, delivering a speech on July 12, 2017 to investors in Ankara, Erdoğan threatened main opposition party leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu by saying that “If you call on people to take to the streets, you will end up in the position of not being able to go out in the street in the end.”

One year on since the failed coup bid of July 15, 2016, which was orchestrated by Erdoğan himself according to in-depth research done by the Stockholm Center for Freedom (SCF), over 50,510 people have been jailed, with many awaiting trial, and more than 169,013 are facing legal action, mostly in the form of lengthy detentions. The situation is not getting any better and in fact Erdoğan is escalating the persecution. It is time to revisit how the human rights issue in Turkey should be taken up, and all the stakeholders who invested in or care about the future of Turkey must now come up with new ways of handling this major crisis on the periphery of Europe.

First and foremost, the international community, especially Turkey’s Western partners, should be able to leverage economic and trade relations to the improvement of its human rights record. It is the only way Erdoğan will respond to appeals and demands. To put it in more concrete terms, the EU’s freezing of accession talks would not nudge Erdoğan in the right direction, and perhaps he would be happy to see the negotiations break down altogether. But he will pay close attention to what that would mean to business and trade ties, especially when it comes to possible revisions to the customs union. If he thinks he would lose trade, investment and tourism big time, thereby threatening the economic underpinnings of his regime, he’ll fold and take a step back. In short, raising the profile of human rights matters while engaging with Turkey would reduce the risk of appeasement.

Moreover, human rights defenders, journalists and civil society groups need all the help they can get from abroad as their support in Turkey has dwindled and most philanthropists are afraid of making donations for fear of being dragged into court under abusive anti-terror laws. The Erdoğan government has seized 965 companies with a total value of over $11 billion on false charges in the last year alone and has seized the personal assets of businesspeople who were seen as supporting critical groups like the Gülen movement.

Highlighting the individual cases of jailed journalists, activists and human rights defenders and following up on their trials may contribute in exerting pressure on the Turkish government.

Considering the fact that many prominent figures who work in the field of journalism and human rights have dispersed outside Turkey following the crackdown, they may come in handy in setting up networks in diaspora with links to Turkey, but they need platforms, resources, expertise and political and financial backing. This valuable human resource may be tapped for sending a message to Turkish society in the local language while covering the rights violations in Turkey for the international community in non-Turkic languages so they can keep abreast of developments in Turkey.

Erdoğan’s destructive path for Turkey depends on a scorched-earth policy, intimidation and blackmail. He has to be confronted head-on. Policy actions by Turkey’s allies and partners have often been too little, too late. Unless urgent measures and necessary brakes are put in place and at the right time to roll back this major slide in Turkey, there is no way of escaping Erdoğan’s runaway train that will cause significant damage not only to Turkey but also to its neighborhood and beyond.