Özcan Keleş*

I recently published a piece titled “Questions we dare not ask: Gülen and the coup” in which I methodically deconstructed the five pieces of “evidence” most repeated by the Turkish government and pro-government media to prove Gülen’s link to Turkey’s failed coup of July 15, 2016. While the piece was positively received, some questioned why I had not addressed the accusations surrounding Adil Öksüz. The reason for this was simple. My piece was in response to an Al Jazeera news report that had uncritically listed and explained these five pieces of “evidence.” The Al Jazeera piece had not listed it, so I did not respond to it. However, based in part on popular demand, here is my appraisal of Adil Öksüz, the so-called civilian imam of the coup.

The challenge with addressing the Adil Öksüz allegation is that everything that we know about him, his alleged involvement in the coup and his denial thereof are all based on government sources and pro-government media. There is no information in the public domain beyond that; neither have we heard his side of the story from him directly. I enquired with Hizmet-related colleagues to establish whether this man was indeed Hizmet-connected. However, none of those I asked knew him or had heard of him prior to this. Either way, this is unsurprising and inconclusive. Given that Gülen categorically denied his involvement in the coup in a series of interviews with both broadcast and print media outlets over a number of days, it is also not surprising that he has not come forward again to additionally deny his alleged collusion with Öksüz. As a result, the analysis below is based solely on government and pro-government media sources.

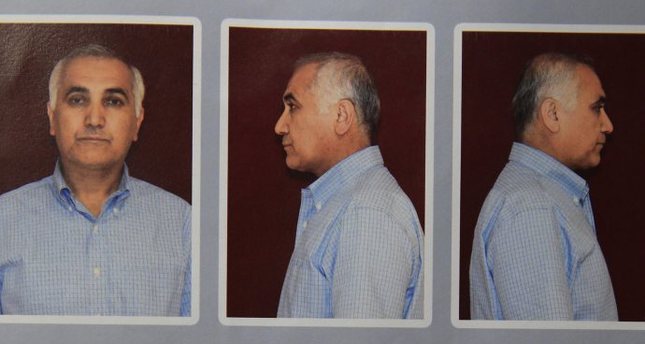

It is alleged that Akıncı Air Base was the headquarters of the failed coup. It is where senior putschist figures were captured and where the chief of general staff was held captive until eventually freed when the air base was re-taken by the regular army, following the exchange of fire, at approximately 10 a.m. on July 16. Of the 98 people arrested at the air base, Öksüz was the only civilian (an assistant professor of theology); he had no permit or acceptable reason for being on site (seen here part naked). Öksüz was kept in detention for two days. He was formally questioned for the purposes of a statement on the morning of July 18. Öksüz denied all charges and claimed that he was never at the air base and that he was detained at a nearby place to inspect a plot of land for sale and brought back to the base. He also claims to have been beaten by police while in detention. His most extensive statement in the media can be found here. According to the prosecutor, his answers were wholly inadequate and untrue.

The prosecutor asked the court to “charge and remand” Öksüz. Judge Köksal Şahin refused and ordered his release. The prosecutor appealed to a court of second instance where Judge Çetin Sönmez upheld the decision of the first court on the grounds of insufficient evidence and, for the second time that day, ordered Öksüz’s release. Security footage shows Öksüz calmly leaving the courthouse and bidding his lawyer farewell. Media reports claim that he flew to Istanbul the same day and visited his in-laws the following morning. He is thought to have then travelled to Sakarya with no further reports in the media as to his movements thereafter. An arrest warrant for Öksüz was issued some time later.

The first set of questions about the government’s claims relate to why Öksüz was at Akinci Air Base in the first place, given the substantial risk of blowing his cover if he was indeed the head of the coup. The putschist generals were allegedly the ones who had spent three days planning the coup and were naturally the ones to lead it, not Öksüz. So why was he on site? Those who claim that Gülen orchestrated this coup suggest that “crypto-Gülenists” work with extreme caution and care. They write their notes on digestible paper, keep to themselves even in ordinary life, and work in a cell-like fashion to prevent one group of crypto-Gülenists from knowing another. Is that description not at complete odds with Öksüz making himself available at the headquarters of the coup? Could a man of such caution not consider the possibility of failure? Is that not why the putschists had taken such care, as argued by some, in ensuring that the coup statement was couched in Kemalist tone and language to avoid detection, especially if the attempt at overthrow failed? And what of the other 97 military officers on site: Were they all Gülenists in whom Öksüz had complete trust? Would an infiltrating man not consider the possibility of double agents amidst the ranks? Was that not the entire purpose of their supposed cell-like structure in the military?

In his statement to the prosecutor, Öksüz strenuously denies all allegations and claims that he was never at the air base but detained nearby. However, we are now told that there is CCTV footage proving that Adil Öksüz was at the base on the night of the coup. How is it that such a secretive man heading such a daring coup does not ensure that the security cameras recording his every move on site are not disabled? This is a man who allegedly avoids being photographed even at his perfectly legal day job (assistant professor), presumably to draw as little attention to himself as possible given his completely illegal alleged night job. How is it conceivable that the same man would be so forgiving of being recorded at the air base? It was clear that the coup was beginning to fail from 1 a.m. local time onwards. Adil Öksüz was arrested at approximately 10 a.m., that is, some nine hours later. If he did not have the cameras disabled before arriving on site, why did he not have the security footage deleted at 1 a.m. or any time thereafter?

Additionally and more importantly, why did he not utilize the intervening nine hours to leave? He was at an air base with helicopters (at least the one that brought the chief of general staff there) and was surrounded by supposed Gülenist pilots. Why did he not have one of these pilots fly him to safety? Surely being caught anywhere else, if caught at all, was far more preferable to being found wandering around as the only civilian at the epicenter of the coup. Yet it is claimed that he remained. If the sheer perplexity of the Adil Öksüz case ended here, we could attribute the above, in the absence of more convincing answers, to the human potential for self-destruction, delusions of grandeur or downright stupidity. The problem is that the story of Adil Öksüz gets even more bizarre from this point onwards.

The Turkish government is very sensitive to the alleged “infiltration” of the Turkish judiciary. They have been purging the Turkish judiciary since 2013. The day after the coup, the Turkish government suspended, and have since dismissed, 2,745 judges and prosecutors. They have not just been purging but also appointing people to the judiciary. In 2014 they introduced a new breed of handpicked “super judges” with extraordinary unilateral powers to whom all politically sensitive cases have since been assigned. In fact, Judge Köksal Şahin was one such super judge, meaning he was strictly vetted for government loyalty and the first to rule for the release of Öksüz. Judge Şahin is known for his punitive and vindictive summary judgments against Hizmet. Pro-government pundit Abdulkadir Selvi swears by the judge’s loyalty to the government. We know from past practice that the government ensures that cases involving critical suspects are assigned to only the most trustworthy of prosecutors and judges. The Turkish authorities have even ensured that the state-appointed lawyer for Gülen is a self-proclaimed anti-Gülenist. So clearly, when it comes to guaranteeing a particular verdict, nothing is left to chance.

That being the case, how could the courts of first and second instance both rule in favor of Öksüz’s release? Being discovered as the only civilian at the headquarters of the coup with a wholly inadequate statement should have sufficed many times over to alert all parties concerned to the importance of the detainee before them. If true, it was without doubt the single most important discovery following the failed coup. In the context of Gülen’s alleged involvement that the detainee was an assistant professor of theology would have only have worked to Öksüz’s disadvantage. When journalists and academics are being detained for “subliminally influencing public opinion in favor of the coup,” how can this man be allowed to walk free? It is completely nonsensical and at complete odds with the current practice in Turkey. (There are also media reports by pro-government newspapers that Öksüz was suspected of being a “Gülenist” as soon as he was detained at the air base and was referred to the prosecutor on those grounds, contradicting the prosecutor’s claim. This one is from Star published on July 21.)

How could the prosecutor not protest immediately, informing the Supreme Board of Judges and Prosecutors (HSYK) or even go directly to the press. If for no other reason, a sense of self-preservation should have compelled the prosecutor to take extraordinary measures to prevent the release of Öksüz. After all, there is precedence for extra-judicial action for exactly this type of scenario in Turkey’s judiciary. Recall how the prosecutor and prison services director unlawfully refused the release order of Hidayet Karaca (director of Samanyolu TV) following his successful bail application and how the two judges of that bail hearing were suspended within two, and arrested and charged, within four days. A more recent example involves a panel of judges who were immediately replaced when three out of four of them decided that a group of 28 academics should not be charged due to a lack of evidence. Needless to say, the renewed court of judges ruled unanimously in favor of charging all of them on terror-related offenses. (See paras. 78-83 for more examples between December 2013 and June 2015.) How can this “system” of forcing through decisions work so well in remote parts of the country concerning individuals with “no case to answer” but fail in one of the most strategically composed courthouses hearing applications concerning the most critical of suspects? How could the prosecutor and his staff allow this to pass?

In an attempt to pre-empt this question, the prosecutor claims that Öksüz was released because there was no intelligence against him. What he means, of course, is that he did not protest in the manner described above despite requesting Öksüz’s release because there was no intelligence against him. How could the absence of intelligence on Adil Öksüz make any difference whatsoever, especially when it is entirely expected for such a linchpin figure to be secretive. If there had been any intelligence on Öksüz prior to this, surely he would have been arrested sooner. So the lack of intelligence is entirely consistent with his alleged role in the coup.

Based on the government paradigm, the only possible explanation is that these judges (and the prosecutor) were deeply embedded “crypto-Gülenists” who had acted against the movement in the past in order to maintain their cover for more critical occasions in the future, such as this. We are told that President Erdoğan receives daily updates on the purge of Gülenists and putschists. So it is reasonable to expect that he was informed of the release of the only civilian detained at the putschist air base. If not then, then surely when the first news report on Öksüz was published, which was by Diken on July 19. (Interestingly the Diken report gives the impression that Öksüz is still being detained when, of course, he had been released a day earlier. Had the police acted straight away, they could have apprehended Öksüz, who visited his in-laws on the same day this report was published.) The Diken news report should have alerted Erdoğan and his government to the great “treachery” of those responsible for Öksüz’s release. As per established practice in Turkey now, this should have led to the immediate dismissal, detainment, asset seizure, passport cancellation and licensing practice revocation of the two judges (and prosecutor and possibly others) involved. Yet the two judges were only just suspended on Aug. 16, that is, almost a month later. That means that during this time, these two judges were allowed to continue adjudicating on critical suspects such as Öksüz and others. Furthermore, none of the punitive summary measures noted above have been taken against these judges.

This delay and form of treatment is totally inexplicable. Recall how then-Prime Minister Erdogan had complained about the lapse of time it had taken the HYSK to suspend the Hidayet Karaca bail-hearing-judges (see this press conference, 0:18 – 0:30) and how the head of that body issued a public apology in response. That lapse of time was two (non-work) days! If we compare this with other cases, there is an inverse relation between the gravity of the alleged treachery and the immediacy and form of punitive action to follow. Like everything else concerning the Adil Öksüz claim, nothing makes sense.

That something does not make sense does not necessarily mean it did not happen. We should not underestimate our capacity for overestimating the level-headedness and intelligence of others. However, had Adil Öksüz’s story begun and ended with his arrest at the air base, perhaps we could have sought recourse in the explanatory power of human stupidity. Yet, as sketched above, it only gets more inexplicable from there onwards.

For Adil Öksüz to be overlooked and released, for it to take so long for this monumental decision to register with the powers that be, for the prosecutor and judges involved in his release to be shielded from all kinds of punitive action that would ordinarily follow, cannot be explained by human error (or alleged Gülenist meddling) but by strategic intervention that only the government could exert. If nothing else, that the two judges were not even suspended for almost a month after their decision and their treatment since demonstrates that this could not have been a Gülenist exercise to save Öksüz. Based on the information at hand, Turkey’s atmosphere of fear, overzealous purge, micro-managing governance and handpicked and strategically composed courthouses exclude any other plausible explanation. All in all, this once again proves that we must be extremely cautious and reserve judgment until we know more.

This article was first published and updates are added in the author’s blog which can be accessed here.

*Özcan Keleş has been chairperson of the London-based Dialogue Society since 2008 and is a non-practicing barrister as well as a full-time Ph.D. candidate in the sociology of human rights at the University of Sussex.