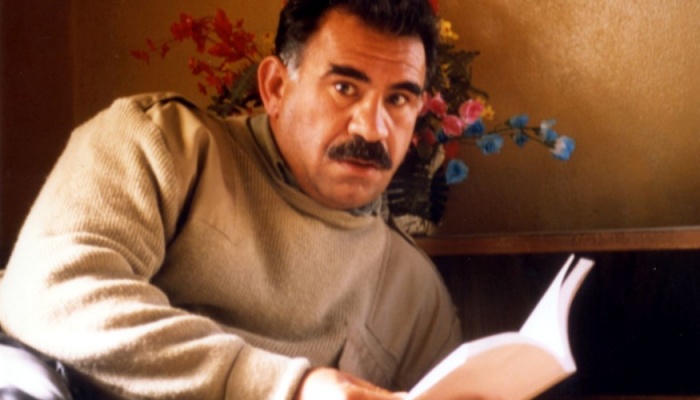

Abdullah Öcalan, the jailed founder of militant group the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), is hailed by many Kurds as an icon, but within the wider Turkish society, many see him as a terrorist who deserves to die.

On Saturday, Öcalan, who has been imprisoned since 1999, received his first political visit in nearly a decade amid signs of a tentative thaw in relations with the Turkish government.

The move came two months after the leader of the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), a close ally of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, offered Öcalan an unprecedented olive branch if he would publicly renounce terrorism. The MHP has historically been a fierce opponent of the PKK.

In a message sent back with his visitors, two lawmakers from the pro-Kurdish opposition Peoples’ Equality and Democracy Party (DEM Party), Öcalan — the man who embodies the decades-long Kurdish rebellion against the Turkish government in search of Kurdish rights — said he was “ready” to embrace efforts to end the conflict.

“I am ready to take the necessary positive steps and make the call,” said the 75-year-old former guerrilla, who also received his first family visit in four years on October 23.

During that visit, Öcalan said he had the necessary clout to shift the Kurdish question “from an arena of conflict and violence to one of law and politics.”

Ankara’s tentative bid to reopen dialogue, nearly a decade after the most recent peace efforts collapsed, comes amid a major regional adjustment following the ouster of Syria’s former president, Bashar al-Assad.

PKK: a Marxist-inspired group

Öcalan founded the PKK in 1978. It spearheaded a brutal insurgency that has killed tens of thousands in a fight originally for independence and more recently, a goal of broader autonomy in Turkey’s mostly Kurdish southeast.

A Marxist-inspired group, the PKK is considered a terrorist organization by Turkey, the United States, the European Union and most of Turkey’s Western allies.

After years on the run, Öcalan was arrested on February 15, 1999 in Kenya following a dramatic operation conducted by Turkish security forces.

He was initially sentenced to death, but Turkey abolished capital punishment in 2004. He has since been held in an isolation cell on Imrali island in the Sea of Marmara, near İstanbul.

For many Kurds, he is a hero they call “Apo” (uncle). But Turks often call him “bebek katili” (baby killer) for his ruthless tactics, including the bombing of civilian targets.

Involvement in peace talks

Tentative moves to resolve Turkey’s “Kurdish problem” began in 2008. Several years later, Öcalan was involved in the first unofficial peace talks, approved when Erdoğan was prime minister.

Seen as the world’s largest group of stateless people, the Kurds were left without a country when the Ottoman Empire collapsed after World War I. The Kurds were promised a country in the Treaty of Sèvres, but it was denied in the superseding Treaty of Lausanne.

Although most live in Turkey, where they make up around a fifth of the population, Kurds also live in Syria, Iraq and Iran, their historical territory.

For hardline Turkish nationalists who support the post-Ottoman idea of “Turkishness” as a national identity, the Kurds simply do not exist.

And not all Kurds back the ideas, let alone the methods, of the PKK.

Led by Hakan Fidan, Erdoğan’s spy chief turned foreign minister, the earlier talks raised hopes of ending the insurgency in favor of an equitable solution for Kurdish rights within Turkey’s borders.

But they collapsed in July 2015, reigniting the deadly conflict.

After a suicide attack on pro-Kurdish demonstrators attributed to Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) in October 2015, the PKK accused Ankara of collaborating with ISIL and resumed its violence with a vengeance.

Turkey’s widescale use of combat drones has pushed most Kurdish fighters into Iraq and Syria, where Ankara has continued raids.

The government has defended its de facto silencing of Öcalan by saying he failed to convince the PKK of the need for peace, raising doubts about how much sway he has over the group.

Captured in exile

Öcalan was born on April 4, 1948, one of six siblings in a mixed Turkish-Kurdish peasant family, in Omerli village, in Turkey’s southeast. His mother tongue is Turkish.

He became a left-wing activist while studying politics at university in Ankara and did his first stint in prison in 1972.

He set up the PKK six years later, then spent years on the run, launching the movement’s armed struggle in 1984.

Taking refuge in Syria, he led the fight from there, causing friction between Damascus and Ankara.

Forced out in 1998 and with the net closing in, Öcalan raced from Russia to Italy to Greece in search of a haven, ending up at the Greek consulate in Kenya, where US agents got wind of his presence and tipped off their ally Ankara.

Lured into a vehicle and told he would be flown to the Netherlands, Öcalan was instead handed over to Turkish military commandos and flown home on a private plane to face trial.