Fatih Yurtsever*

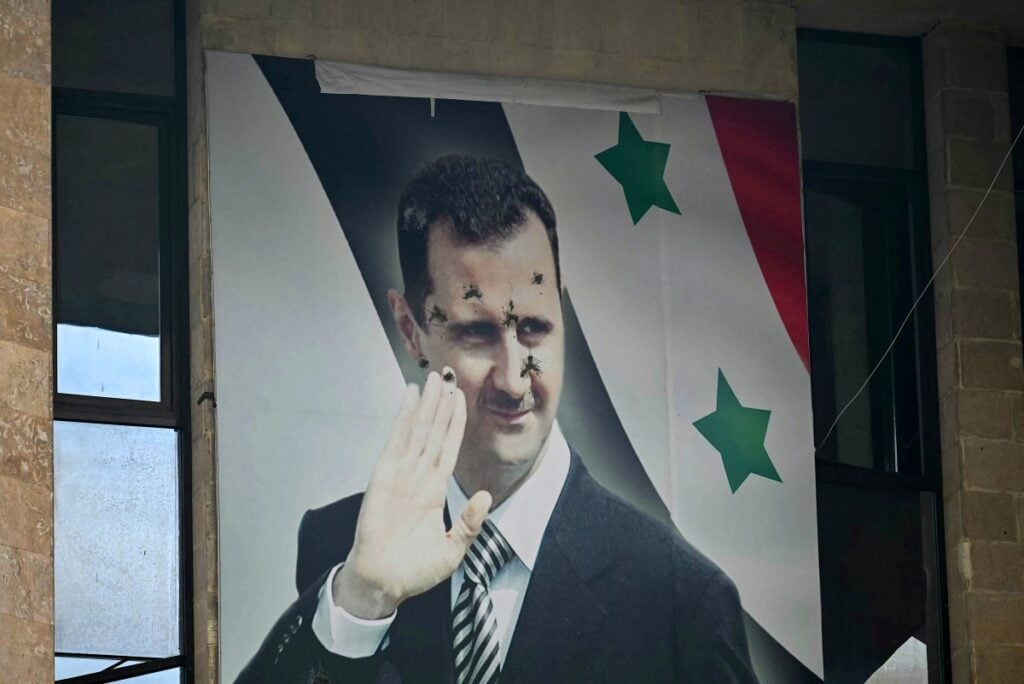

The fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria, a nation once heavily supported by Iran and Russia, has unleashed a new wave of geopolitical competition that is dramatically reshaping the power dynamics in the Middle East.

After a 13-year civil war, Assad was finally ousted by a rebel offensive led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and the Assad family fled to Russia. This has created a vacuum in governance with various rebel groups controlling different parts of the country.

With Iran and Russia — the traditional power brokers — seeing their influence in Damascus increasingly diminished, the two regional heavyweights of Israel and Turkey are working aggressively to fill the emergent vacuum of power.

Assad’s downfall began with a popular uprising in 2011, which escalated into civil war. Turkey initially supported regime change but later shifted to supporting groups like HTS to strengthen its influence in northern Syria. Turkey’s strategy was to capitalize on the decreasing influence of Iran and Russia in the region and fill the void with its own power, both diplomatically and militarily.

Turkey reportedly supported the offensive by HTS to unseat Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in a change of alliances that further distances the country from long-standing allies Iran and Russia.

Tehran has implied that HTS would not have been able to achieve such territorial gains without the support of Turkey.

With Assad now fallen, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is said to have emerged as the leading figurehead of the Sunni Muslim world. Erdoğan has long sought to make his country one of the regional powers in the Middle East.

Erdoğan has said on more than one occasion that had the Ottoman Empire been divided up differently after its defeat in World War I, a number of Syrian cities, including Aleppo and Damascus, could have been part of modern-day Turkey.

After Assad was ousted earlier this month, Turkey was quick to reopen its embassy in Damascus and has provided additional support to HTS to help create the country’s new Islamist system of governance.

In a plan revealed by Murhaf Abu Qasra, Syria’s newly appointed interim defense minister, the various opposition groups are to unite into a single military structure.

Turkey aims to help the Syrian opposition groups that toppled Bashar al-Assad create this unified military force of 300,000 troops in the next 18 months, with the core role played by Turkish military advisers, a pro-government Turkish news website said on Monday.

Turkish Armed Forces personnel are to assist at five strategic locations, according to the Türkiye news website.

Gen. Ahmad Osman, a military representative of Syria’s transitional leadership, had earlier estimated that the core force in the first phase would be 70,000 to 80,000 troops. He has placed in this core force some 50,000 soldiers of the Syrian National Army and 40,000 fighters previously with HTS, as well as former officers not implicated in abuses during the Assad regime.

Once a permanent government is formed in Damascus, Turkey also hopes to negotiate a maritime exclusive zone delimitation agreement with Syria in an attempt to increase energy exploration in the Mediterranean, Transport and Infrastructure Minister Abdülkadir Uraloğlu said Tuesday, according to a Bloomberg report.

The would-be deal would extend the countries’ “zones of influence” over energy resources, Uraloğlu said, noting that any agreement would be in line with international law.

Hosting about 3 million Syrian migrants, Turkey is also eying opportunities for Turkish companies in post-war reconstruction in Syria.

Turkey’s relationship with Kurdish groups in Syria, particularly the People’s Protection Units (YPG), is complicated. While Turkey considers the YPG a terrorist organization linked to the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), the US has cooperated with these groups, viewing them as crucial allies in the fight against the extremist group Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). This has strained US-Turkey relations and highlighted a diplomatic dilemma for both countries as they navigate competing interests in the region.

It is actually the emergence of an autonomous Kurdish region along its border that most worries Turkey, which it regards as a serious security threat in view of possible links with Kurdish separatist sentiment within the country.

The military presence of America in northeastern Syria serves a dual purpose: to secure oil fields as a counter against the resurgence of ISIL and to provide a buffer against Iranian influence, which goes toward supporting Kurdish autonomy within a unified Syrian state.

The US has tried at times to appease Turkey by restricting YPG movements near the Turkish border and holding consultations on de-escalation. However, in the face of recent Turkish threats, the US has repeated its support for the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) based on their role in counter-terrorism and ensuring stability. There is, however, a balance in the tension whereby the US tries to advance its strategic interests without overly antagonizing Turkey, a NATO ally. The latest statements by US officials still express support for the SDF, with no immediate policy shift because of Turkish pressures.

For the United States, controlling the Syria-Iraq border is crucial to preventing the movement and logistical support of pro-Iranian militias. Given this, it seems unlikely that the US will approve any Turkish military intervention that could undermine the YPG’s control of this border region. In doing so, one possible way to make Turkey’s position pragmatic is by pressuring the YPG through groups such as HTS to coerce them into laying down arms. The problem is convincing the YPG to yield to the call, given the prolonged presence of the Turkish military presence within Syrian territory. The PYD may well propose a precondition of the withdrawal of the Turkish forces in return for the laying down of arms by YPG detachments, which finally will end Turkey’s influence in Syria.

It is, therefore, too early to call Turkey an undisputed victor in Syria’s geopolitics. Such a strategy, which looks to shape the future of Syria through an unwieldy group like HTS — notoriously hard to control — may bring about unpredictable, even unfavorable, consequences for Turkey. Besides, international support for Turkey would rapidly dissipate if civil war broke out again in Syria, with Turkey standing to be blamed.

Therefore, as was revealed by Russian President Vladimir Putin during the annual review meeting traditionally held in Russia every year, the biggest winner that has emerged in Syria so far is Israel.

Lina Khatib says in her article in Foreign Policy magazine that the fall of the Assad regime is definitely going to bring an end to the regional order under the dominance of Iran and give birth to a new regional order is to be led by Israel and its allies.

For Khatib, this shift is going to change Israel, once a state encircled by enemies and seeking legitimacy in the region, into one of the key agenda setters in the Middle East. Given its close relations with both the United States and Russia, Israel will use this to its advantage by pushing itself to be the central player in the region.

The fall of the Assad regime has already directly affected Iran’s ability to maintain its “Axis of Resistance,” most notably the break in the land bridge utilized for supply routes to Hezbollah in Lebanon — a very important route indeed for the transfer of weapons and personnel. Now, with Assad gone, Israel can far more effectively block or at least monitor these supply routes, substantially reducing the threat from Hezbollah along its northern border.

Israel has seized the opportunity to degrade Syrian military capabilities post-Assad, striking at air defenses, missile depots, naval assets and chemical weapon sites. It weakens not only any future Syrian state but also ensures that these weapons do not fall into the hands of extremist groups or remain a threat to Israel.

Israel invaded the part of Syria known as the Quneitra Governorate, more precisely the demilitarized or buffer zone east of the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights established following the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. One of their targets was the village of Al-Hamidiyah and the incursion extends to strategic locations such as Mount Hermon, where Israel took control of an abandoned Syrian military outpost.

But of course, while Israel and Turkey are probably the two dominant actors in Syria today, eventually, their policies will have to be accommodated within the US vision of a new Middle East order — a strategy that really crystallized after the Hamas attack on Israel on October 7, 2023. The core of the US vision is how to contain Iran’s political-military influence in Syria, Lebanon, Yemen and Iraq; promote the normalization of Saudi-Israel relations; and convert the Middle East into a Chinese- and Russian-free trade and energy corridor for the EU countries and India. That said, despite years of political rhetoric by Israel and Turkey demonizing each other as some kind of rival, both Tel Aviv and Ankara acknowledge the pragmatic reality that both of their Syria policies should fit with American goals in the region. The chances are slim of a direct confrontation between Turkey and Israel in Syria and there is plenty of room for cooperation around points of mutual concern. The US needs both countries to contain Iranian influence in Iraq, making cooperation all the more imperative.

* Fatih Yurtsever is a former naval officer in the Turkish Armed Forces. He uses a pseudonym due to security concerns.