Vedat Demir*

Since the corruption and bribery investigations into members of the ruling party in December 2013, Turkey has been experiencing the biggest “crisis decade” in the republic’s history.

The bribery and corruption investigations shook the country back in 2013. The probe implicated, among others, the family members of four cabinet ministers as well as the children of then-prime minister and current president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

To shut down the investigations, Justice and Development Party (AKP) chairman Erdoğan meddled in the judicial system and set in motion a process that slowly caused the state’s constitutional order and institutional structure to disintegrate.

First, the media, then the judiciary, and finally, all state institutions were affected by this process. Erdoğan gained power through corruption and used it to create a monolithic media landscape dominated by his AKP, and he silenced the remaining few opposition media outlets through repression.

Dozens of journalists and writers were fired from their media outlets, detained and arrested. The government seized and closed down opposition broadcasters, newspapers and news agencies despite the freedoms enshrined in the constitution.

A state of emergency imposed after a coup attempt on July 15, 2016, which Erdoğan called a “gift from God,” also rendered parliament powerless. The government established special courts that acted at the government’s behest. Judges were arrested for their decisions for the first time in the republic’s history.

The country was from then on governed by decree-laws. More than 100,000 state employees were dismissed through lists published in the Official Gazette, allowing the AKP to create a bureaucracy under its control.

With the dismissal of nearly 4,000 judges and prosecutors, including members of the Constitutional Court, and the arrest of thousands, the judiciary became completely subordinate to the government. Turkish prosecutors, under government control, opened terrorism investigations into nearly 2 million people.

Currently, not even the slightest criticism of the government is tolerated in the country. A new law also aims to silence dissenting voices on social media, the only remaining space for dissent.

On April 6, 2017 a referendum held under the state of emergency and pressure from the government formalized a de facto one-man rule. In this process Erdoğan ignored the constitution, the law and basic legal principles and abolished the institutional structure of the state in all but name.

The AKP reversed Turkey’s 200-year-old process of modernization and Westernization. Erdoğan has started to talk about the country’s accession to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, which includes Russia, China and Iran. Despite being a member of NATO and an aspiring European Union member, the West now views Turkey as unreliable and unpredictable.

Turkey has experienced significant crises in the past. World War I, when Turkey, then the Ottoman Empire, was on the brink of extinction, and World War II, when Turkey was threatened with invasion and war, are among the most critical crises Turkey has witnessed. The ability of the leaders who emerged during these times to overcome the crises shaped the destiny and future of Turkey.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s military and political genius enabled the establishment of an independent state and a secular republic within today’s borders. The policies and diplomatic maneuvers of his successor, İsmet İnönü, during and after World War II kept Turkey out of the war and secured its place in the democratic Western bloc. In this regard, it is necessary to recognize the crucial role of leaders in managing international and political crises that affect the futures of countries.

Turkey is in a critical period. While all the democratic achievements of the republic are being destroyed one by one, the country’s moribund “democracy” and “rule of law,” which have been reduced to constitutional texts, are waiting for Erdoğan’s final blow.

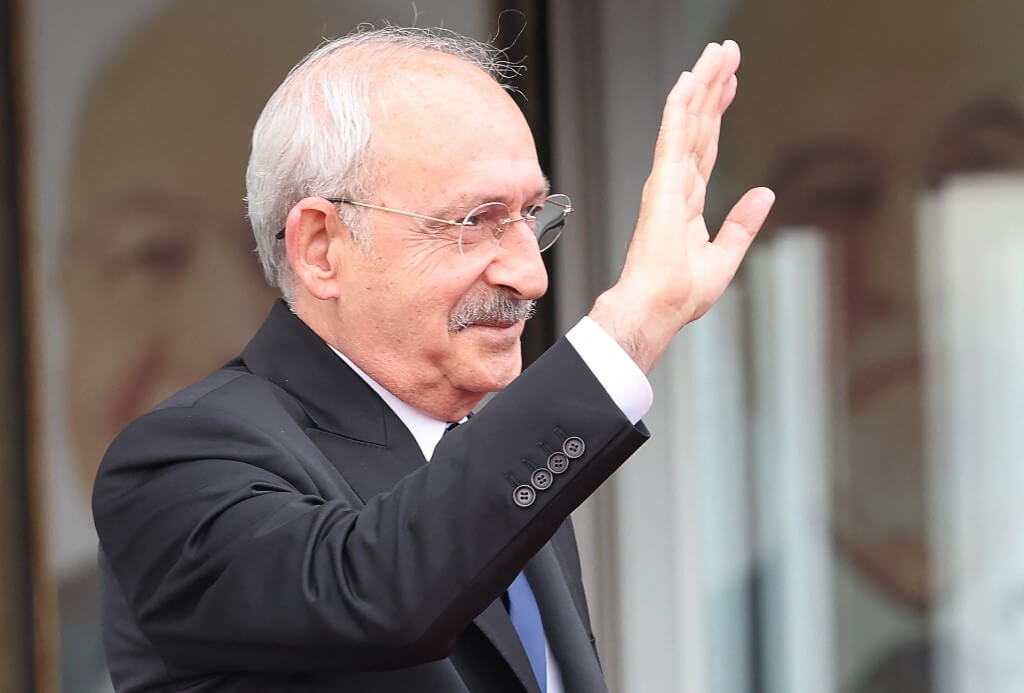

The “Table of Six” formed by political parties united against Erdoğan’s “People’s Alliance” has taken a historic step in this process. It announced Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, leader of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), as the alliance’s candidate for the presidential election to be held in two months.

This decision has generated great hope and excitement in the country in the name of democracy and justice.

The alliance against Erdoğan

One year ago, on February 12, 2021, six opposition parties joined forces upon the call of the CHP chairman.

These parties, consisting of former AKP members, nationalist, Islamist, Kemalist, conservative, leftist and liberal-leaning politicians, published a text of joint consensus advocating a “strengthened parliamentary system” against the “presidential system of government” that is the basis of Erdoğan’s authoritarian regime.

There was a short-lived Kemalist-Islamist coalition in the 1970s and a center-right Kemalist coalition in the 1990s. But this is the first time that an alliance has been formed that unites almost all political currents in Turkey. The most striking aspect of the alliance is that the six parties, whose predecessors have fought each other fiercely since Turkey’s transition to a multiparty system in 1946, and whose union was not thought possible, have set a goal against the Erdoğan regime within the framework of democracy, rule of law, freedoms and norms of the European Union. This is because the Western and European orientation is still the main driving force of Turkish democracy, as it was in the past.

Kılıçdaroğlu is the most crucial player in the alliance and managed to convince the other factions of his candidacy. He is an interesting figure in Turkish politics. A quiet, level-headed leader who does not incite his supporters at rallies, he has little charisma compared to Turkish political actors of the past.

However, it did not take long for many to realize that behind this image lay a brilliant strategist, a tactician who could make changes depending on the situation, and a patient chess master.

Kılıçdaroğlu was elected chairman of the main opposition party, the CHP, in 2010. Leading the party of Atatürk, the victorious Ottoman general of Turkey’s War of Independence who established a secular, republican regime in the Islamic world, is no easy task.

He was born in Tunceli (Dersim) in 1948, a town that the then-CHP-led Turkish government always viewed with suspicion because of the Alevi Kurdish uprisings in the 1930s, and he managed to become the leader of the party Atatürk founded.

It was challenging for Kılıçdaroğlu to become the leader of a party that was nationalist, authoritarian-leaning and secularist but still retained the traditional Turkish Sunni structure in which solid and rigid factions and deep state actors were very influential, with his Kurdish and Alevi identity excluded from the official ideology.

Transforming this party might have proven impossible if Kılıçdaroğlu hadn’t worked tirelessly, despite all the difficulties, to rebrand the CHP as a more pluralistic and democratic party and to open it up to different groups. He put candidates from the right-wing camp on the parliamentary election lists.

In 2014 he nominated an academic known for his conservative views as a presidential candidate.

However, realizing that the rigid political blocs in Turkey would not change any time soon and that his party would not garner more than 30 percent of the vote this way, Kılıçdaroğlu tried another method: electoral alliances.

In the 2018 elections, he included the leaders and candidates of minor parties that could not enter parliament on his parliamentary lists and ensured their representation in parliament. He transferred 15 lawmakers to a newly formed party to facilitate its participation in the elections.

Kılıçdaroğlu reaped the fruits of all these efforts in the 2019 local elections, winning 11 metropolitan municipalities with the electoral alliance he had formed with four parties, including Ankara and İstanbul, which had been AKP strongholds for 25 years. Despite occasional strategic and tactical changes, the CHP leader never abandoned his primary goal: He always defended democracy and the rule of law.

In 2017 he organized a 25-day “justice march” from Ankara to İstanbul. He challenged the government narrative of the July 15 coup attempt and argued that the coup was a false flag in which the AKP was involved. As a result, he became a presidential candidate with the support of almost the entire opposition, which opposes the authoritarian regime of President Erdoğan.

Barring extraordinary events and interventions by his regime, Erdoğan seems to have a serious opponent who could challenge his rule for the first time in 20 years.

* Dr. Vedat Demir is a professor from the Department of Social and Political Science at the Free University of Berlin.