by Abdullah Bozkurt

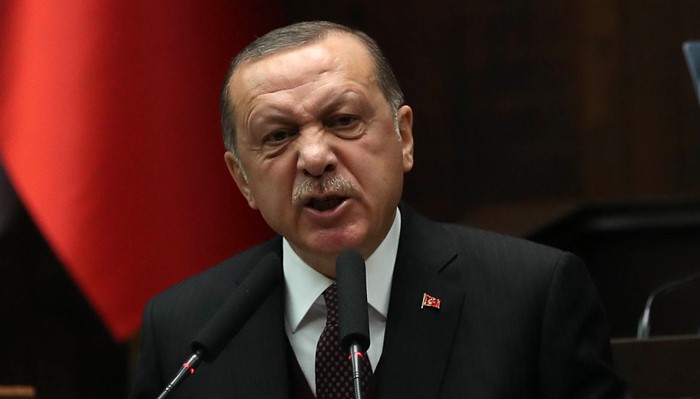

Turkey’s Islamist President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has ratcheted up his usual anti-Western diatribe, taking it a step further to threatening Europe in particular with a flood of returning jihadists, warning that countries better cooperate with Turkey or risk seeing a wave of terrorism in their midst.

Addressing his own party members in Parliament on Feb. 20, 2018 Erdoğan explained that Turkey has deported 6,000 foreign nationals suspected of being connected to the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, ISIS or Daesh, its Arabic acronym). “Do you know what this means?” he asked, immediately answering his own question by saying, “This means such a [big] number of potential Daesh people, most living in countries with welfare and a pretense of security, continue to operate.” Describing these deported suspects as “ticking time bombs,” Erdoğan urged countries to find ways of working with the Turkish government to avoid losses and counter the threat. He warned countries not to embrace terrorism, or face terror themselves. In case his warnings are not heeded by some countries, Erdoğan predicted that the nationals of those countries “will seek a hiding place in fear come tomorrow.”

In other words, Erdoğan and his Islamist regime, which helped transfer so many foreign jihadists to conflict zones in Syria and Iraq, was inadvertently saying that his government may very well cash in on his investment of proxy groups that it nurtured for years. Turkey’s notorious spy agency, the National Intelligence Organization (MIT), led by his confidante, die-hard Islamist Hakan Fidan, has been busy in trafficking, arming and funding various foreign jihadist groups in Syria. As they return from the lost battles in Syria and Iraq, jihadists receive a homecoming party in Turkey, where they regroup and recompose to be sent away on other missions Erdoğan decides to pursue. Passports and travel documents were arranged with ease, sometimes with the direct help of the Erdoğan government, in clandestine operations.

What this autocratic leader was in fact saying was that those countries that support his legitimate critics such as journalists, lawmakers and human rights defenders better brace themselves for the terror he would be unleashing. Some factions that joined the Turkish military under the guise of the Free Syrian Army during Operation Olive Branch, which targeted Afrin in the north of Syria, are linked to various jihadist groups. Many were trained in camps inside Turkey or in the territory of Syria where Turkey has maintained direct or indirect control. In fact, thanks to the Afrin offensive, jihadist groups caught a break as the battle against ISIL by the US-led coalition was distracted by the new developments in Afrin.

To be blunt, there has never really been a crackdown on ISIL networks in Turkey as most, if not all, are released in what I call the revolving door policy of the Erdoğan government that has been in effect in the criminal justice system for the last four years. The innocent critics of government policies such as journalists and opposition politicians faced the wrath of the government with vicious prosecutions and heavy sentences on dubious charges in the absence of any evidence. Yet ISIL militants who were caught with overwhelming evidence of criminal activity such as weapons and explosives were quickly let go. Successful prosecutions of ISIL cases are very rare, and most detainees including foreign fighters were let go during trial phase with full knowledge that they wouldn’t show up for the next hearing or would become fugitives when the verdicts were rendered.

Perhaps that explains the reluctance of the Turkish government to share data on ISIL. Erdoğan and his cabinet members who publicly claim that ISIL is engineered by the US to create a pretext for imperialist military intervention in the Middle East are not forthcoming with the figures on ISIL suspects in Turkey. In fact, they treat the information on how many were actually convicted after detention and trial almost as a state secret.

Nevertheless, we have some figures available from the rare statements by authorities that may shed some light on the overall picture. Speaking at a meeting on the judicial apparatus in the southern province of Antalya on Feb. 10, 2018, Justice Minister Abdulhamit Gül said the number of ISIL militants who were detained or convicted was 1,354 without providing a breakdown of how many of them were convicted. At the time, the total number of people who were jailed either pending trial or convicted and serving time was 223,589. In other words, less than one percent (0.60 percent to be exact) of the prison population in Turkey comprises ISIL suspects and convicts.

On Feb. 17, 2018, appearing at the Munich Security Conference a week later, Turkish Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım told the high-profile international audience that there are roughly 10,000 ISIL suspects in Turkish prisons. In other words, the prison population of ISIL in Turkey had jumped from 1,354 to some 10,000 within a week, which is unlikely. Perhaps he wanted to give the impression that Turkey has really been cracking down on the ISIL network when in fact he inflated figures and lied about them. By the way, the same government has locked up close to 60,000 innocent people in around a year, which includes hundreds of journalists, thousands of doctors, lawyers, judges, prosecutors, academics, human rights defenders and others on terrorism charges without any evidence of violence or terrorism.

We have updated numbers on foreign ISIL militants in Turkish jails as of March 2017 thanks to a parliamentary question posed by main opposition party lawmaker Gamze Akkuş İlgezdi. Responding to her question, the Justice Ministry stated that 470 foreign ISIL militants were jailed. Of these, 28 had been convicted and were serving time while others were being kept in pretrial detention. In July 2016, the number of convicted ISIL militants was seven, while detainees who were awaiting the conclusion of trial proceedings while in detention totaled 513 (of these, 274 were foreign nationals).

The Turkish government’s unwillingness to share updated figures about successful convictions of ISIL suspects coupled with a systematic and deliberate policy of preventing the legislative branch from investigating its network with dozens of motions to probe ISIL defeated by Erdoğan’s party give credence to serious allegations about government connections to jihadists. There is no counter-narrative from the government to undermine the jihadist ideology, either. In fact, what we have been hearing from Erdoğan and his government ministers is a replay of what jihadists are saying for non-Muslim countries. The current Islamist government is only pretending to be cracking on jihadist networks when in fact it is protecting them by preventing the criminal justice system from successfully convicting and locking them up. The uptick in figures of police raids and detentions of ISIL suspects often coincides either with intensified international pressure or after a deadly terror attack that is blamed on ISIL. Most detainees were simply let go in stages when public attention was diverted to some other pressing issue.

In any case, Erdoğan’s threat of exporting ISIL militants abroad, especially to European countries, should not be taken lightly or considered to be a bluff. The track record of militants who wreaked havoc in European capitals show they have all spent time in Turkey, where they were linked with the ISIL network under the watch of Turkey’s MİT. For example, Hayat Boumeddiene, a French national of Algerian origin who was the female accomplice of the Islamists behind the deadly attacks in Paris in January 2015, came to Turkey on Jan. 2, 2015 and stayed in Istanbul for two days before going to the border province of Şanlıurfa, where she spent four days before finally crossing into Syria. Turkish intelligence had tracked her movements and listened to her conversations yet allowed her to work closely with ISIL cells in Turkey.

Ismail Omar Mostefai, a Frenchman of Algerian descent who was involved in the Bataclan concert hall attack that killed 89 people (130 in total in coordinated attacks) on Nov. 13, 2015, travelled to Turkey at the end of 2013 and moved on to Syria afterwards. He was known to Turkish intelligence, which tracked his movements and shared details with French authorities in December 2014 and June 2015.

Brussels bombers Ibrahim El Bakraoui and his brother Khalid el-Bakraoui, who were involved in the deadliest act of terrorism in Belgium’s history on March 22, 2016, which killed 32 civilians, also turned out to be in Turkey. Ibrahim El Bakraoui, a Belgian national of Moroccan descent, flew to Turkey’s tourist resort city of Antalya on June 11, 2015 and moved on to the border province of Gaziantep on June 14. He was caught three days later as he was trying to cross into Syria and deported to the Netherlands on July 14, 2015. His brother Khalid el-Bakraoui entered Turkey on Nov. 4, 2014 through an Istanbul airport. He was let in without any trouble. He left Turkey 10 days later on his own. The entry ban for Khalid el-Bakraoui was imposed on Dec. 12, 2015, after Belgium issued an arrest warrant for him on the same day.

The accomplices of Anis Amri, a Tunisian national who drove into the Christmas market in Berlin on Dec. 19, 2016, killing 12 people, were detained in Turkey after the incident. German citizens of Lebanese origin identified as Muhammed Ali K., Yusuf D. and Bilal Yosef M. were arrested in March 2016 in an operation conducted by the police acting on an intelligence tip as the suspects were about to leave Turkey. A fourth man, a German national of Jordanian descent, was also detained in Turkey’s western city of İzmir.

Akbarzhon Jalilov, a Russian national who was born in Kyrgyzstan, killed 14 people in a blast on the St Petersburg metro on April 3, 2017. He came to Turkey in late 2015 and had spent a year there before he was deported on immigration violations in December 2016. Rakhmat Akilov, the Uzbek national who rammed a truck into a crowd in Stockholm and killed five people on April 7, 2017, also had spent some time in Turkey, tried to cross into Syria and was shipped back to Sweden. Salman Abedi, a British national of Libyan descent, killed 22 people at a pop concert in the northern English city of Manchester when he blew himself up on May 22, 2017. Before the attack, he was in Libya and returned to the UK via Turkey and Germany. He was believed to have been supported by accomplices in Turkey. Youssef Zaghba, one of the three London bridge attackers on June 3, 2017 who killed eight, was detained in Italy in 2016 when he attempted to travel to Syria via Turkey. Zaghba had dual Moroccan and Italian citizenship.

With his own confidante Fidan, a pro-Iranian figure who emulated Iran’s experience of investing in radical religious proxies for leverage, at the helm of the notorious Turkish intelligence organization, Erdoğan’s threats should be considered a serious challenge for the security of Europe as well as for Russia and China, two countries that sent the most jihadists to Syria through Turkey. Considering that not only the Turkish diaspora but also non-Turkish Muslim groups were lobbied, supported and funded by Erdoğan regime operatives in Europe and other places, embedding jihadists in already settled migrant communities would not be a problem for a state actor that has all the resources available to cloak its clandestine activities.