An article published by Internet newspaper The Daily Dot on Friday shows how the leaked emails of Berat Albayrak, the Turkish energy minister and son-in-law of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, have revealed the rise of pro-government Twitter trolls in Turkey.

The article was penned by Efe Kerem Sözeri.

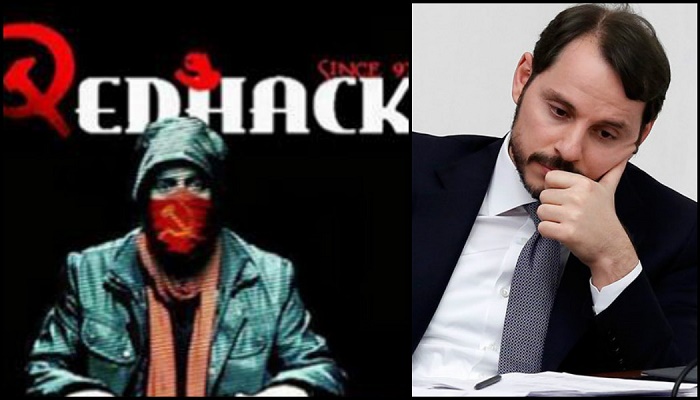

Albayrak’s emails were hacked by RedHack, a Marxist hacker group in late September. The group threatened to leak the content if Turkey did not release leftist dissidents, including a pro-Kurdish political party official and a novelist, from pre-trial detention.

At the end of RedHack’s deadline last Monday, the group began leaking documents obtained from Minister Albayrak’s personal email accounts, which he reportedly used for government business.

According to The Daily Dot, which obtained the 17 GB data dump in full and reviewed its content, the leak comprises 57,623 emails dating from April 2000 to the present day.

Albayrak’s emails show plans to use the power of social media for government propaganda and that the silencing of government critics dates back to the Gezi protests, which were sparked in June 2013 in protest of government plans to demolish a park in Istanbul’s Taksim neighborhood.

The protests later turned into nationwide anti-government demonstrations due to the government’s brutal response to the protestors.

“… one of Albayrak’s producers in the Turkuvaz Media, Yalçın Şen, sent a screenshot of an online news article under which he wrote a comment in support of Erdoğan’s crackdown on Gezi protesters. This was, perhaps, the very first astroturfing attempt in the post-Gezi period, similar to Putin’s trolls who flooded news websites with pro-Putin comments. But the real mass-scale effort was still in the making,” Sözeri wrote.

In an email dated June 18, 2013, Halil Danışmaz from the US-based Turkish Heritage Organization suggested Albayrak set up a team of professional graphic designers, coders and former army officers who had received training in psychological warfare.

Based on the advice of US-based Turkish analyst Cüneyt Arvasi, Danışmaz suggested that such a team would be necessary to counter critical narratives in foreign media outlets and could weaken the protest networks on social media. Three days later, Arvasi came up with a detailed document titled “Feasibility Etude” about how youth can be influenced by humor and slang while delivering a message and how opposition media organizations can be undermined by attacking their employees. His method of discrediting influencers in the opposition was black propaganda, such as “exposing their drug use.” In the document he requested a $209,000 budget for the technical equipment and core members of this team.

Danışmaz and Arvasi did not respond to requests for comment.

Simultaneously, Albayrak’s wife, Esra, arranged a social media monitoring agency for sentiment analysis of online content about the government, according to a June 22 email. The agency’s presentation, attached to that email, offered to set up a 60-member team for PR and crisis management on social media.

In another email from June 28, the core team initiated one of its first planned hashtag campaigns “#DirenÇözüm,” using the protest’s keyword “diren” (“resist”), while also suggesting that the government wanted a peaceful solution. Justice and Development Party (AKP) lawmakers tweeted the exact phrases that were suggested in the email: “6 aydır kan akmıyor, insanlar ölmüyor” (“no blood has been shed for 6 months,” referring to Erdoğan’s peace process with the Kurds, which later failed).

Within months after the nationwide protests that brought 2.5 million people to the streets, the AKP managed to set up a 6,000-member social media team mostly from its youth branch. While the team was fully functional in harassing journalists, they evidently failed in the face of growing evidence revealed by an investigation in a corruption scandal in December 2013. As a last resort, the Erdoğan government banned Twitter and YouTube days before local elections in March 2014. Erdoğan’s control over traditional media also increased: Public broadcaster TRT was fined for giving 125 times more coverage to him than all other candidates combined in the run-up to the presidential elections of August 2014.

Erdoğan eventually became Turkey’s president.